William Lloyd Garrison Hopes For Freedom For the Slaves of “our guilty land”

"...that this may prove the long-desired jubilee...".

In 1831, Garrison began publishing the abolitionist paper, The Liberator, and two years later helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society. In speaking engagements and through his newspaper and other publications, Garrison advocated the immediate emancipation of all slaves, and favored the break-up of the Union rather than cooperation with the slaveholders....

In 1831, Garrison began publishing the abolitionist paper, The Liberator, and two years later helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society. In speaking engagements and through his newspaper and other publications, Garrison advocated the immediate emancipation of all slaves, and favored the break-up of the Union rather than cooperation with the slaveholders. This was an unpopular view during the 1830’s, even with northerners who were unsympathetic to slavery. From the 1840’s to 1854, Garrison continued to hammer at his theme of freedom for blacks, and his views began to gain some traction in the north. However, the nations’s attention at the time was mainly focused on Texas, the Mexican War, the newly-acquired West, and the attempts to adjust differences between the sections that led to the Compromise of 1850. All that changed when the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed by Congress on May 30, 1854. The Act served to repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820 which prohibited slavery north of latitude 36°30´, and infuriated many in the North who considered that Compromise line to be permanent. In the South the new law was supported and pro-slavery men rushed in to settle Kansas.

This situation brought Abraham Lincoln out of retirement from politics, and made Garrison, if anything, increasingly radical. On July 4, 1854, he scandalized everybody by burning the U.S. Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Act at an Anti-Slavery rally in Framingham, Massachusetts. As the new year of 1855 dawned on a shaken and polarized nation, Garrison recognized this as an opportunity, as indeed it proved, to advance the cause of the slave.

One of the most prominent figures in the history of American economics, Francis Amasa Walker was brevetted brigadier general at age 24 in the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. He became superintendent of the U.S. Census at 30, then went on to serve as the 3rd president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), president of the American Statistical Association (ASA) and the American Economic Association (AEA) (which, before the days of the Nobel Prize, would award the "Walker Medal" to leading economists for lifetime achievements). As a 14 year old, he wrote Garrison and received this response.

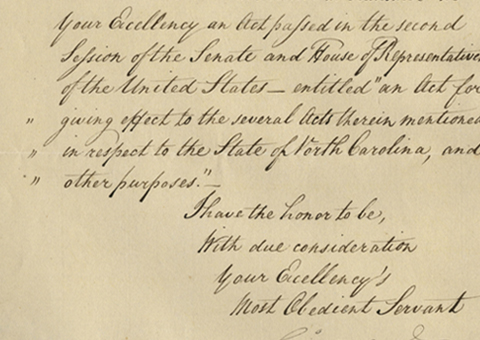

Autograph Letter Signed, Biston, January 1, 1855, to the young Walker, whom he addresses as “Dear Friend.” "Pardon me for so long neglecting (by an oversight) to comply with your request for my autograph…It will be safe for you to have my handwriting in your possession in Massachusetts, but hardly so in Carolina. Wishing you ‘a happy new year,’ and that this may prove the long-desired jubilee to all the enslaved in our guilty land…" The country would edge closer to Civil War that year, and though 1855 did not bring the jubilee, that triumphal moment was just 8 years away.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services