President Woodrow Wilson, In Paris for the Peace Conference Ending World War I, Makes Plans To Speak at an American War Cemetery Honoring the Fallen

The only letter of Wilson we can recall mentioning the Paris Peace Conference reaching the market

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

At the cemetery, he would pledge himself to the soldiers who fought “that there should never be a war like this again …. This can be done. It must be done.”

The Paris Peace Conference, also known as Versailles Peace Conference, was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of...

At the cemetery, he would pledge himself to the soldiers who fought “that there should never be a war like this again …. This can be done. It must be done.”

The Paris Peace Conference, also known as Versailles Peace Conference, was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. This was the first great world war, one that had stretched across continents and left over 38 million casualties, with some 18 million killed. It took place in Paris during 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities. The Conference convened in January and Wilson was present from the start. After a brief return to the U.S. in February, he came back to France in March and stayed for over three more months.

In mid-May, Wilson received an invitation from the U.S. Ambassador to France to speak on Memorial Day at a cemetery where American dead were buried. The ceremony was initially to be held at the Bagnolet Cemetery but eventually was moved to the Suresnes Cemetery – the first cemetery for American war dead in France. Wilson did speak, and he could not help thinking in terms of the Gettysburg Address: “The League of Nations is the covenant of governments that these men shall not have died in vain.” If the honored dead could be buried in America, their dust would ”mingle with the dust of the men who fought for the preservation of the Union …. Those men gave their lives to secure the freedom of a nation. These men have given theirs to secure the freedom of mankind.” In the course of this speech Wilson vented his scorn for the European politicians with whom he had been forced to deal: “You are aware, as I am aware, that the airs of an older day are beginning to stir again, that the standards of an old order arc trying to assert themselves again. There is here and there an attempt to insert into the counsel of statesmen the old reckonings of selfishness and bargaining and national advantage which were the roots of this war.” But “let these gentlemen not suppose that it is possible for them to accomplish this return to an order of which we are ashamed and that we are ready to forget. They cannot accomplish it.” The Americans had come to France to see “that there should never be a war like this again …. This can be done. It must be done.”

Around the same time as this invitation was extended, negotiations heated up at Versailles, with the harshness of proposed sanctions leading to disagreements among the Allied powers. Summarizing this, the South African representative wrote to Wilson on May 14, warning that it was “impossible for Germany to carry out the provisions of the Treaty.” He asked Wilson to try to make the terms more “moderate and reasonable.” But Wilson replied that while the terms were “undoubtedly very severe indeed,” he did not find them “unjust,” because of the “offense against civilization which the German State committed.”

On May 29, the German delegation returned. The German foreign minister, Brockdorff-Rantzau, refused to sign the treaty, calling it a “death sentence.” The effect of this refusal was stunning, and it caused the British to reconsider the treaty.

The next day Wilson would attend the ceremony at the graves of Americans who had fought and died so that no more wars like this would take place.

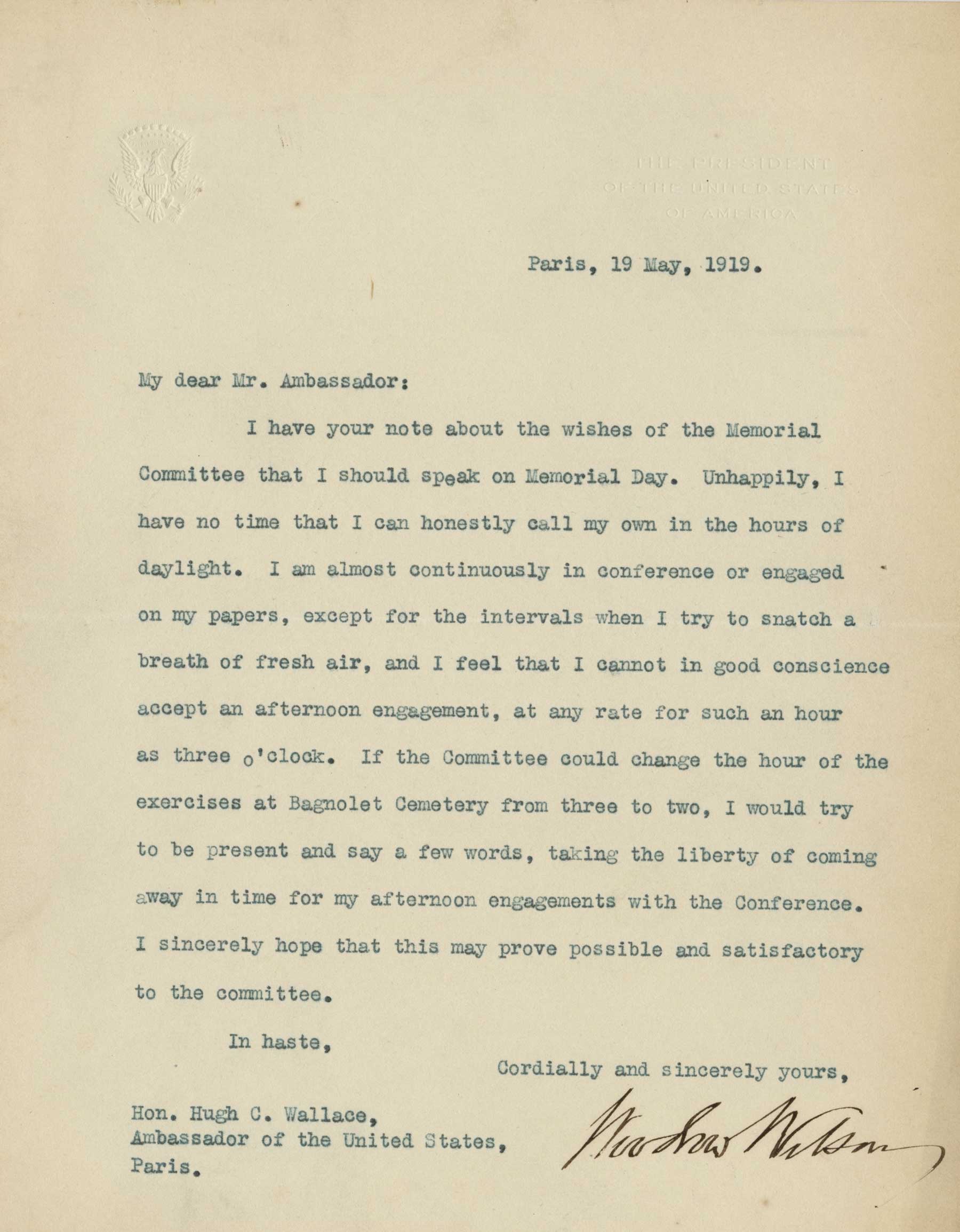

Typed letter signed, from Paris, May 19, 1919, to the Ambassador to France, Hugh C. Wallace, making arrangements to attend the ceremony and speak, and mentioning the ongoing negotiations. “My dear Mr. Ambassador: I have your note about the wishes of the Memorial Committee that I should speak on Memorial Day. Unhappily, I have no time that I can honestly call my own in the hours of daylight. I am almost continuously in conference or engaged on my papers, except for the intervals when I try to snatch a breath of fresh air, and I feel that I cannot in good conscience accept an afternoon engagement, at any rate for such an hour as three o’clock. If the Committee could change the hour of the exercises at Bagnolet Cemetery from three to two, I would try to be present and say a few words, taking the liberty of coming away in time for my afternoon engagements with the conference. I sincerely hope that this may prove possible and satisfactory to the committee.”

This Conference was one of the most consequential events of the 20th century. Its major decisions were the creation of the League of Nations; the five peace treaties with defeated enemies, including the Treaty of Versailles with Germany; the awarding of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as “mandates“, chiefly to Britain and France; reparations imposed on Germany, and the drawing of new national boundaries to better reflect forces of nationalism. The treaty with Germany provided in section 231 that the guilt for the war be laid on “the aggression of Germany and her allies”. As to whether the terms were too harsh, history has judged that to be the case, and the treaty was one of the leading factors leading to World War II.

This is the only letter of Wilson from Paris and directly about the Versailles Conference that we can recall having reached the market.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services