In An Unpublished Letter, Written Just Two Months Before Leaving for Philadelphia to Chair the Constitutional Convention, George Washington Discloses His Personal Need for Funds and Negotiates the Sale of Some of His Western Land to a Revolutionary War Colonel Who Had Been with Him at Valley Forge

A remarkable statement, showing that on the eve of such a monumental undertaking, Washington was working to remain debt free

This letter appears in no known compilations of Washington’s correspondence and at the time of discovery was unknown to scholars

Perhaps more than any other leader of the Revolutionary Era, George Washington was shaped by his experiences in western lands. Washington came away from his early ventures in the West with a...

This letter appears in no known compilations of Washington’s correspondence and at the time of discovery was unknown to scholars

Perhaps more than any other leader of the Revolutionary Era, George Washington was shaped by his experiences in western lands. Washington came away from his early ventures in the West with a conviction that the destiny of Virginia, and later of the United States itself, would be one of expansion. Washington was a youth when he began surveying in the Shenandoah Valley and was only twenty-one when he made a perilous journey across the Allegheny Mountains to command the French to withdraw from the Ohio region claimed by Britain. When Washington returned to Williamsburg with news of the French defiance, he brought back a vision of the almost inconceivably rich interior beyond the barrier of the mountains. That vision remained with him and he invested in western lands for his whole life and worked to politically and commercially link the west with the eastern seaboard. Through purchases, trades, and as payment for his military service, George Washington eventually amassed more than 70,000 acres in what would today be seven different states and the District of Columbia. The schedule of property he appended to his will in the summer of 1799 listed his then-current land holdings as 52,194 acres, exclusive of the 8000 he also held at Mount Vernon.

One of Washington’s holdings was a 1,644–acre tract of land, called Washington’s Bottom, on the Youghiogheny River in western Pennsylvania. This was his first land acquisition west of the Allegheny Mountains, a remarkable moment in the life of the budding land owner. He obtained the tract in 1768, and first visited it in 1770. In need of a settler to hold the tract against squatters and to begin clearing it for profitable cultivation, Washington was pleased in the fall of 1772 to receive a letter from Gilbert Simpson, Jr., son of a reliable man who for many years rented land from him on Clifton’s Neck at Mount Vernon, proposing a partnership to develop Washington’s Bottom. Washington would provide the land; Simpson his personal services as manager.

Washington found himself shortly of money in 1787. In February of that year he wrote to his mother in response to her request for money, “Those who owe me money cannot or will not pay it without Suits and to sue is like doing nothing, whilst my expenses, not from any extravagance, or an inclination on my part to live splendidly but for the absolute support of my family and the visitors who are constantly here are exceedingly high; higher indeed than I can support, without selling part of my estate which I am disposed to do rather than run in debt…”

Israel Shreve was colonel of the 2nd New Jersey Regiment in the American Revolution. He was at the battles of Quebec, Brandywine, and Germantown, and then spent the cold winter of 1777, short of clothing and food supplies, with Washington’s troops at Valley Forge. In July of 1779, Shreve and the 2nd N.J. Regiment joined Major General John Sullivan in his campaign against the Tory-allied Iroquois Indians. Shreve retired from the military in 1781. He maintained a correspondence with Washington over many years.

On March 5, 1787, Shreve first attempted to buy Washington’s Bottom. On March 5, Shreve wrote Washington, “…Since which I have Several times heard you have about Sixteen Hundred Acres of Land at or near Redstone In Pennsylvania called Washingtons Bottoms, which you Incline to Sell. I have not Seen the Lands But am Pretty well informed of the Situation Quality and Improvements thereon, by persons of my Acquaintance that Live near the Premises—If you do Incline to Sell the sd tract of Land altogether with the Improvements thereon, and Willing to take final Settlement Notes for pay, I should be glad to Purchase of you, said Notes are on Interest which Interest I am told will pay Tax in Virginia Eaqual to Cash, If So I hope you will oblige me In takeing them &c.—If my proposals are agreeable Please as soon as Convenient, to let me know your price…” Seven days later, Shreve again wrote Washington, saying “Dear Gen., Since Writeing the first Letter dated the 5th Inst. I have had further Information respecting your Determination to Sell the Said Land. I hope I can Bring about a Bargain with you. I am Destitute of a Suitable farm in this State to Live Comfortable upon—and most of my Property is in final Settlement Notes, If you are Desirous to Sell Said Land, I could give a Sum in Such property the Interest of which would be Considerable more than the Rents ariseing from the Lands.”

By settlement notes, Shreve refers to bounty land warrants. The federal government provided bounty land for those who served in the Revolution. It was first offered as an incentive to serve in the military and later as a reward for service. The federal government reserved tracts of land in the public domain for this purpose. The states of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia also set aside tracts of bounty land for their Revolutionary War veterans. A veteran requested bounty land by filing an application at a local courthouse. The application papers and other supporting documents were placed in bounty land files kept by a federal or state agency. If the application was approved, the individual was given either a warrant certificate to receive land or scrip which could be exchanged for a warrant. Later laws allowed for the sale or exchange of warrants.

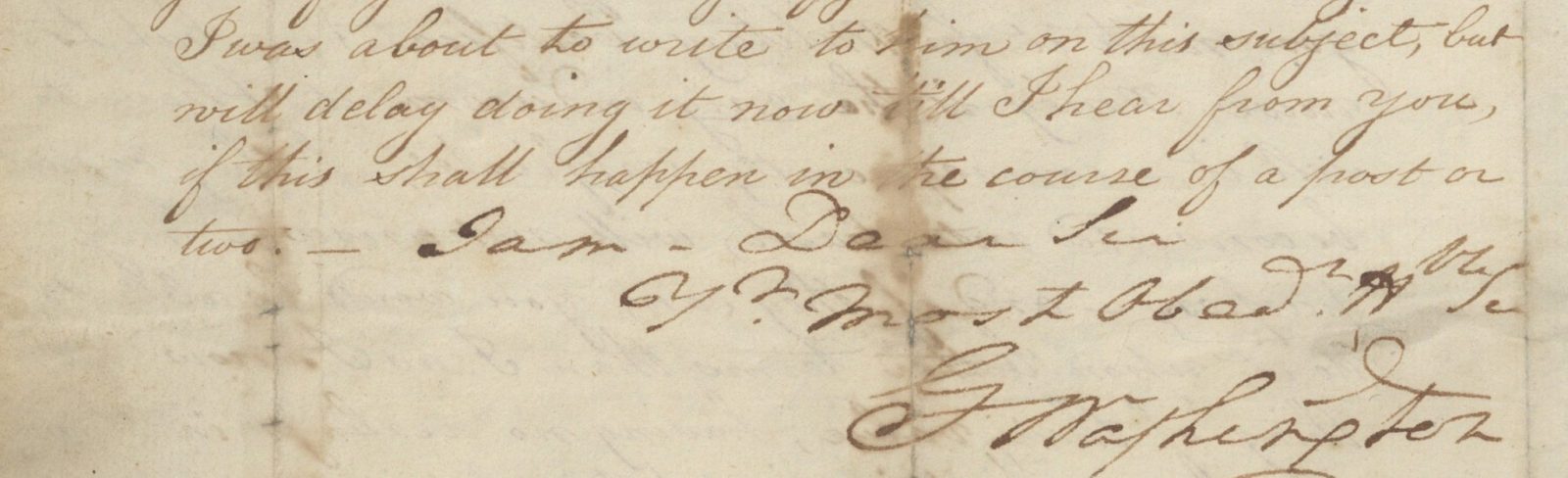

Washington responded in this letter. The text is in the hand of Tobias Lear, executive secretary to George Washington from 1786 to 1799, and the signature and closing are in Washington’s hand. Letter signed, Mount Vernon, March 20, 1787, to Shreve, admitting he was hard pressed for funds, and outlining his terms to sell the land, terms which did not include bounty certificates. “Your favor of the 5th inst. came duly to hand. The land you mention is for sale, & I wish it was convenient for me to accommodate you with it for military certificates; but to raise money is the only inducement I have to sell it. Consequently, certificates if they cannot be converted into cash, will not answer my purpose. And if they can you would be able to do it on better terms than I, as I know nothing of their value, having no dealings in them.

“My price is 40/ Pennsylvania money per acre if sold altogether, which is one third less than small tracts of land in the vicinity, of less intrinsic value, have sold for. One fourth of the money to be paid down – the other three fourths in three annual payments, with interest.

“As you say you are well acquainted with the land from information, I should only add that there are appearances of very rich oar [copper ore] within 20 yards of the mill, and within 5 or 600 yards of navigation, which must, I think, add greatly to the value of it. I have says thus much because a gentleman in that country who does business for me has lately written to me that he can sell the land if I will empower him to do it.

“If therefore you have any inclination to purchase upon the terms here mentioned (which I shall not deviate from), I should be glad if you would signify it without delay, as I was about to write to him on this subject, but will delay doing it now till I hear from you, if this shall happen in the course of a post or two.” This letter is unpublished and previously not known to exist. Just two months later, Washington would go to Philadelphia to chair the Constitutional Convention.

In the end Shreve succeeded only in leasing the 600–acre portion of the tract with the mill on which Gilbert Simpson, Jr., had lived until September 1785. But Shreve again approached Washington on June 29, 1794, about buying the tract at Washington’s Bottom, and in January 1795 Washington agreed to sell to Shreve all 1,644 acres of the Washington’s Bottom tract for £4,000 Pennsylvania currency. The sale was completed on July 31, 1795.

We’ve never before heard Washington disclose a need for funds like this, and perhaps just as surprising, the letter is unpublished. Unpublished letters of Washington seldom turn up anymore.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services