The New York Business Community and Nation Bind Together to Help Thomas Jefferson, At the End of His Life, Collecting Money to Relieve His Staggering Debt and Help Him Keep Monticello

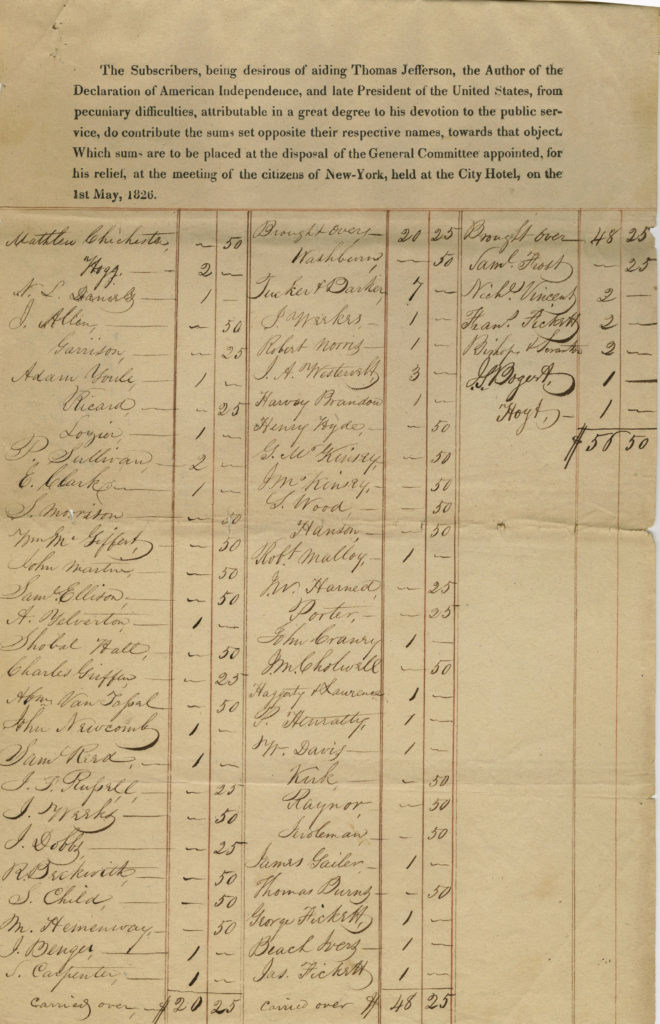

The Original, Unpublished Tally Sheets for the Incoming Funds From All 12 Districts Responsible for the Aid Collection for Henry Rutgers, Containing a List of Those Districts Reporting, Listing the Contributions of Notable the New Yorkers Spearheading and Supporting the Effort

Records show only one such later sheet in the University of VA and none having reached the market

This effort was in part spearheaded by Henry Remsen, Jefferson’s longtime secretary before Meriwether Lewis, and these copies belonged to him: “The Subscribers, being desirous of aiding Thomas Jefferson, the Author of American Independence,...

Records show only one such later sheet in the University of VA and none having reached the market

This effort was in part spearheaded by Henry Remsen, Jefferson’s longtime secretary before Meriwether Lewis, and these copies belonged to him: “The Subscribers, being desirous of aiding Thomas Jefferson, the Author of American Independence, and late President of the United States, from pecuniary difficulties, attributable in a great degree to his devotion to the public service, do contribute the sums set opposite their respective names, towards that object…”

Just months before Thomas Jefferson’s death, his family attempted to alleviate the crushing burden of his $100,000 personal debt by arranging a public lottery.

His grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, to whom Jefferson had entrusted his business affairs in 1817, was forced to admit that, after eight years, he was unable to stabilize them. The old patriarch’s financial burdens, brought on chiefly by the failure of his estate to handle his large obligations, were staggering. This, coupled with the bankruptcy of Randolph’s brother-in-law Wilson Cary Nicholas, whose note Jefferson had endorsed in 1817, gave him the coup de grace. The Spring of 1826 was a gloomy one for Jefferson and the household. The portents for Monticello and its occupants were ominous.

The aged patriot and his grandson cast about for possible means of relief. From the recesses of a still active mind Jefferson drew out the age old expedient of disposing of a part of his holdings by lottery. This had frequently been done in Virginia under similar circumstances in times past. However, in 1826 lotteries were prohibited by law, and this made it necessary for him to obtain permission from the State Legislature. He petitioned that body and accompanied his petition with a dissertation on lotteries in which he attempted to anticipate any possible objections.

The bill was not to have smooth sailing; in fact, there were strong swells of opposition. At home some demurred on religious and moral grounds, while others thought it would hurt Jefferson’s good name. Legislative opposition came from friend and foe: some were in no mood to assist the arch democrat even in an almost dying gesture, while the rest were honestly concerned with the effect on his reputation. The petition was first introduced on the floor of the House of Delegates on February 8, 1826, and it failed.

The bill was presented again after an impassioned plea by Delegate George Loyall. The vote on the bill was taken on February 20 and it passed the House by 125 to 62 and the Senate by 13 yeas to 4 nays. The bill authorized Jefferson “to dispose of any part of his real estate by lottery, for the payment of his debts.” A proviso which affected earlier plans allowed no more money to be raised by the sale of tickets than the amount of a fair evaluation. The depressed value of Albemarle County land necessitated the inclusion of nearly all Jefferson’s Albemarle and possibly some of his Bedford lands if the prize were to be attractive. When Randolph suggested Monticello might be included, his grandfather was reported to have “turned white,” but he realized the hopelessness of the situation and “after a while came into it.”

When the law authorizing the lottery was passed, Randolph thought of turning to lottery brokers in one of the large northern metropolitan centers. He decided in the early Spring that Yates and McIntyre of New York City might handle the scheme. They agreed, and added their agents’ services without compensation. Their prospectus advertised that the winning combination would be drawn from 11,477 tickets at $10 each, a rather high figure for that day. The following prizes were listed: 1 prize, the Monticello estate valued at per subjoined certificate under oath at $71,000; 1 do. the Shadwell Mills at $30,000; 1/3 do. the Albemarle Estate at $11,500; in total the estimated value was $112,500. Unfortunately Randolph failed to give complete control of the scheme to his brokers in a timely fashion.

Because of the activity occurring in their city, the business and government community in New York became very aware of Jefferson’s plight. People were touched, and wanted to do something to help. A Committee of Citizens was organized under the leadership of Mayor Philip Hone and other patriotic groups. They believed, and convinced Randolph, that the needed money could be raised by voluntary public subscription in a dignified manner and at less expense and trouble to Jefferson than an auction. Their plan promised that Jefferson would not lose his much beloved patrimony, Monticello. Final authority to begin the lottery auction was postponed pending these private efforts,.

Jefferson did not object to the promises held out by Hone and the others, but he was disturbed over the effect the subscriptions might have on the lottery, whose plans were now well advanced. Under the hope of quicker, easier, and less costly results, and the influence of Randolph, the old man gave in. The lottery was quietly laid aside. Mayor Hone’s Committee raised $6,500; a Committee in Philadelphia subscribed $5,000; $3,000 came from Baltimore and lesser sums from elsewhere. The total raised was about $16,500. This gave Jefferson some measure of relief, but it did not solve his problems because his total indebtedness was so much larger. The results, however meager, cheered the old gentleman in his last months for they did indicate the esteem in which he was held by so many of his fellow citizens. Even before his death signs indicated that the subscriptions might prove abortive. They finally did. Happily, Jefferson never knew this when he died on July 4, 1826.

The fundraising was organized by district. There were 12. Each ward or district was responsible for collecting and reporting back those contributions.

These are the original tally sheets, showing ongoing fundraising efforts, including seven of the original subscription sheets, a working document registering the incoming funds and from which district and collected by whom, which mention the committee, indicate their purpose, and the names and amounts pledged of the subscribers. At the top of each is this statement: “The Subscribers, being desirous of aiding Thomas Jefferson, the Author of American Independence, and late President of the United States, from pecuniary difficulties, attributable in a great degree to his devotion to the public service, do contribute the sums set opposite their respective names, towards that object. Which sums are to be placed at the disposal of the General Committee appointed, for his relief, at the meeting of the citizens of New York, held at the City Hotel, on the 1st of May, 1826.”

Contributors in this group are led by Col. Henry Rutgers. After serving as captain in the Continental Army, Congress appointed Rutgers a “Deputy Commissary General of Musters” with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He went on to become a full colonel of New York militia and a member of the state legislature. A noted philanthropist, he funded a college in New Jersey that was then named after him. Because of their long tradition over four generations as brewers, the Rutgers family has been deemed “the first of the ‘brewing families’ in America.” Another was his nephew, philanthropist John P. Crosby.

Henry Remsen, banker and real-estate investor, has signed. He was a clerk in the United States Office of Foreign Affairs by 1784 and served as chief clerk in the Department of State during the first part of Jefferson’s tenure as Secretary of State. He left that post in 1792 to become first teller of the New York branch of the Bank of the United States. Remsen became a cashier at the Manhattan Bank about 1801 and served as its president from 1808 until about 1825. This grouping comes from his papers.

Among the dozens of others signing and / or and making contributions were city commissioner Abraham Dally; a number of harbormasters, shipbuilders, and merchant captains, including John Rooks, Henry W. Bool, C. Bergh, and Obed Smith; and John J. Cisco, banker and Assistant United States Treasurer.

On the back of page 1, someone has tallied the incoming funds, by ward, and noted how much money had been collected to date. Four districts had yet to report in.

The Jefferson Papers shows only one similar subscription sheet. We are not aware of any that have reached the market prior to this one, which was passed down through Henry Remsen’s descendants until now.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services