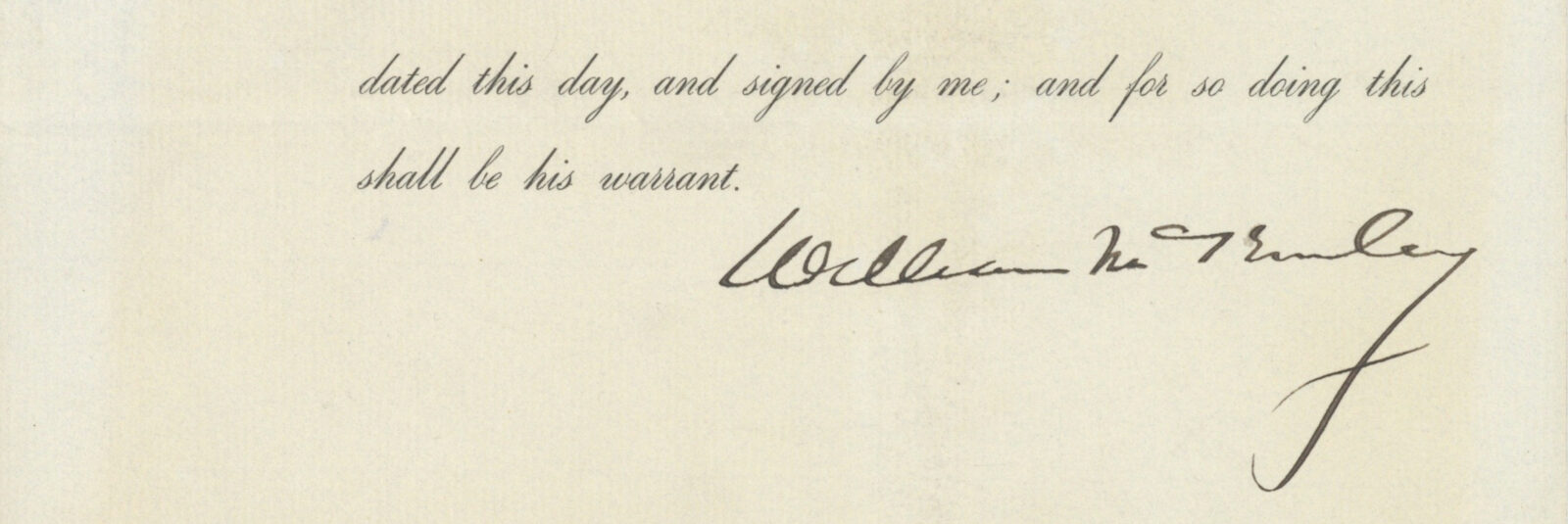

President William McKinley Orders the Immediate Evacuation of Spain from Cuba, the Key Peace Term of the Treaty Ending the Spanish American War

This is a document of extraordinary importance concerning the Spanish-American War and the rise of the U.S. to International Prominence

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

Cuba was the prime Spanish base in the Caribbean for centuries. Christopher Columbus claimed the island for Spain in 1492, and the Spanish conquest began in 1511, when the settlement of Baracoa was founded. The native Indians were eradicated over the succeeding centuries, and African slaves, from the 18th century until slavery...

Cuba was the prime Spanish base in the Caribbean for centuries. Christopher Columbus claimed the island for Spain in 1492, and the Spanish conquest began in 1511, when the settlement of Baracoa was founded. The native Indians were eradicated over the succeeding centuries, and African slaves, from the 18th century until slavery was abolished in 1886, were imported to work the sugar plantations. Cuba revolted unsuccessfully against Spanish rule in the Ten Years’ War in 1868–78; a second war of independence began in 1895. In 1897, in a desperate effort to hold on to its last two possessions in the Americas, Spain granted Cuba and Puerto Rico, a broad array of rights including those under Title I of the Spanish Constitution, which bestowed all the rights of Spanish citizens and gave universal suffrage to all males more than twenty-five years old. It did not satisfy the Cubans and the struggle was ongoing.

The United States had a long-term negative view of Spain and wanted it out of the Western Hemisphere. This was in part because of anti-Catholic feeling in the U.S. going back to colonial days. Then, in the War of 1812, the Spanish were allies of Britain, angering many Americans. The prospect of taking East and West Florida from Spain encouraged southern support for the war in the U.S. Moreover, the Spanish policy of supplying Creek Indians with arms and ammunition through their territories in Florida further strained relations with the Americans on the frontier, and made Spain a threat to American expansion. The U.S. obtained West Florida in 1819, and purchased East Florida from Spain in 1821. In the years before the American Civil War, Americans in the South wanted to obtain Cuba as the chief goal in a plan to make the Caribbean part of a slavery empire. But colonies, such as Cuba and Puerto Rico, remained in Spain’s grasp.

From 1895–1898, the violent conflict in Cuba captured the attention of Americans because of the economic and political instability that it produced. The long-held U.S. interest in ridding the Western Hemisphere of European colonial powers and American public outrage over brutal Spanish tactics created much sympathy for the Cuban revolutionaries. By early 1898, tensions between the United States and Spain had been mounting for months. After the U.S. battleship Maine exploded and sank in Havana harbor under mysterious circumstances on February 15, 1898, U.S. military intervention in Cuba became likely.

On April 11, 1898, President William McKinley asked Congress for authorization to end the fighting in Cuba between the rebels and Spanish forces, and to establish a “stable government” that would “maintain order” and ensure the “peace and tranquility and the security” of Cuban and U.S. citizens on the island. On April 20, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution that acknowledged Cuban independence, demanded that the Spanish government give up control of the island, foreswore any intention on the part of the United States to annex Cuba, and authorized McKinley to use whatever military measures he deemed necessary to guarantee Cuba’s independence.

The Spanish government rejected a U.S. ultimatum and immediately severed diplomatic relations with the United States. McKinley responded by implementing a naval blockade of Cuba on April 22 and issued a call for 125,000 military volunteers the following day. That same day, Spain declared war on the United States, and the U.S. Congress voted to go to war against Spain on April 25.

The future Secretary of State John Hay described the ensuing conflict as a “splendid little war.” The first battle was fought on May 1, in Manila Bay, where Commodore George Dewey’s Asiatic Squadron defeated the Spanish naval force defending the Philippines. The Spanish Caribbean fleet under Adm. Pascual Cervera was located in Santiago harbor in Cuba by U.S. reconnaissance. An army of regular troops and volunteers under Gen. William Shafter (including future president Theodore Roosevelt and his 1st Volunteer Cavalry, the “Rough Riders”) landed on the coast east of Santiago and slowly advanced on the city in an effort to force Cervera’s fleet out of the harbor. On June 10, U.S. troops landed at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba and additional forces landed near the harbor city of Santiago on June 22 and 24. On July 1 took place the Battle of San Juan Hill, victory in which boosted the Rough Riders and their leader Roosevelt into instant fame. On the naval front, after isolating and defeating the Spanish Army garrisons in Cuba, the U.S. Navy eyed the Spanish Caribbean squadron on July 3 as it attempted to escape the U.S. naval blockade of Santiago. In the ensuing battle all of his ships came under heavy fire from U.S. guns and were beached in a burning or sinking condition. Santiago surrendered to Shafter on July 17, thus effectively ending the brief but momentous war.

On July 26, at the behest of the Spanish government, the French ambassador in Washington, Jules Cambon, approached the McKinley Administration to discuss peace terms, and a cease-fire was signed on August 12. The war officially ended four months later, when the U.S. and Spanish governments signed the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. The Treaty guaranteed the independence of Cuba, and also forced Spain to cede Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States. Spain also agreed to sell the Philippines to the United States for the sum of $20 million. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty on February 6, 1899.

Document signed, Executive Mansion, Washington, August 19, 1898, ending Spain’s presence in Cuba, which was the primary reason the war had been instigated, by ordering American representatives to negotiate for and carry out Spain’s evacuation of Cuba.“I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of State to cause the Seal of the United States to be affixed to the commissions and full powers of Major General J.F. Wade, U.S.V., Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, U.S.N., and Major General M.C. Butler, U.S.V., as United States commissioners to arrange and carry out the details of the immediate evacuation by Spain of Cuba and the adjacent islands.”

Following the war, U.S. forces remained in Cuba until 1902, when the United States allowed a new Cuban government to take full control of the state’s affairs. As a condition of independence, on May 20, 1902, the United States relinquished its occupation authority over Cuba, but claimed a continuing right to intervene in there.

This is a document of extraordinary importance relating to the Spanish-American War and U.S. relations with the Caribbean.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services