The Last Days of Abraham Lincoln: Signed the Day He Made His Final Speech – April 11, 1865

One of his final official acts and among the final items he signed in those fateful days, appointing a founder of the National Colored Home

For generations in a private collection and not known to have survived

On April 9, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was paying a visit to Secretary of State William H. Seward when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton burst in with the news: Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Ulysses S....

For generations in a private collection and not known to have survived

On April 9, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was paying a visit to Secretary of State William H. Seward when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton burst in with the news: Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army earlier that day, essentially ending the bloodiest conflict in American history.

The following morning, April 10, after Stanton jolted the region awake with a 500-gun salute at dawn, the populace of Washington, D.C. took to the streets in celebration. A crowd of several thousand gathered outside the White House, clamoring for the President before he finally appeared in the second-story window to acknowledge their presence. Revealing that he planned to formally address the occasion in due time, Lincoln noted that he was particularly fond of the song “Dixie,” the anthem of the South, and asked the band assembled to strike up a version of the “lawful prize” acquired with the Union victory.

Just one day later, on April 11, Lincoln returned to that second-story window to deliver what would be his final prepared words to the public. “We meet this evening,” he said, “not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart. The evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of the principal insurgent army, give hope of a righteous and speedy peace whose joyous expression cannot be restrained. In the midst of this, however, He from whom all blessings flow, must not be forgotten. A call for a national thanksgiving is being prepared, and will be duly promulgated. Nor must those whose harder part gives us the cause of rejoicing, be overlooked. Their honors must not be parceled out with others. I myself was near the front, and had the high pleasure of transmitting much of the good news to you; but no part of the honor, for plan or execution, is mine. To Gen. Grant, his skillful officers, and brave men, all belongs. The gallant Navy stood ready, but was not in reach to take active part.”

He then pivoted to the crucial topic of Reconstruction, citing Louisiana as a state that had made good-faith efforts to offer freed enslaved people the opportunity for a public education. Although he was disappointed that voting rights were not part of the package, the President stressed that it was better to build on a flawed plan than to start from scratch, rhetorically asking whether a party “shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it?”

In the audience, actor and Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth seethed as he listened to ideas to reconfigure the fallen Confederacy. Having already launched a failed attempt to kidnap the President, he swore to colleagues that this time Lincoln would pay with his life.

On Wednesday, April 12, following breakfast, Lincoln’s friend, former Illinois Republican Senator Orville Browning, introduced Lincoln to William C. Bibb, an influential Unionist from Montgomery, Alabama. The three men had a discussion about reconstruction, and Lincoln issued a pass permitting Bibb to pass through Union lines and return to his home state. Alfred de Pineton, the Marquis de Chambrun, states that he and Lincoln “spoke at length of the many struggles he foresaw in the future and declared his firm resolution to stand for clemency against all opposition.” Lincoln visited Secretary Stanton at the War Department office at about 5 p.m.

On Thursday, April 13, 1865, Lincoln’s last full day alive, he made an early morning visit to the telegraph office at the War Department Office. He exchanged pleasantries with telegraph operator Charles A. Tinker, before proceeding to Secretary Edwin Stanton’s office. Grant returned to Washington that day and met with Lincoln. They discussed military matters and problems associated with reestablishing Union authority in Confederate states. Later in the day, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was also a part of these discussions.

That day brought more festivities and the chance for Lincoln to catch up with his oldest son, Robert, a captain on the general’s staff. They enjoyed a relaxed breakfast on the Good Friday morning of April 14, the elder imparting fatherly advice about the importance of finishing up law school. The President then attended his weekly cabinet meeting, which touched on the installation of a temporary military government in Virginia and North Carolina.

But Lincoln seemed most eager to go out on a private carriage ride with his wife. Following a rough period in which they endured an all-encompassing war and the death of an 11-year-old son, the quiet excursion seemingly sparked an awakening from a winter’s discontent, as they revisited dormant memories and mused on the places they could visit together. Mary later told friends that she had never seen her husband so “cheerful.”

Following an early supper, the Lincolns prepared to attend a production of the comedy Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre. The Grants, initially scheduled to join them, wound up declining the invitation because Mrs. Grant wanted Grant, herself, and their son Jesse to leave the capital for the Grants’ cottage in Burlington, New Jersey. Grant conveyed his regrets to Lincoln, as did Secretary Stanton, who chided the President on the dangers of appearing in such a public space. The President and First Lady were eventually accompanied by a younger couple, Clara Harris and Major Henry Rathbone.

The play was already underway when the orchestra launched into “Hail to the Chief,” and Lincoln bowed to the applauding audience before settling into the presidential box with his party. Onlookers noted that Mary seemed quite cozy with her husband, often drawing his attention to something that caught her fancy on stage.

Shortly after 10 p.m., Booth was allowed entry to the presidential box by an usher. With the policeman assigned to guard Lincoln nowhere in sight the assassin had a clear path to his target. Waiting for a line that drew laughter, he quietly approached Lincoln and shot him in the back of the head.

Autographs of Lincoln from these last days are extremely rare. A search of The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln” indicates that Lincoln is known to have signed just two or three dozen things in these final four days. Many of them are now in institutions and thus not available to private collectors. We had one 21 years ago, and it’s the only one we’ve had in all our decades.

One of the things he signed was a Treasury appointment. The National Colored Home, founded to relieve the suffering of destitute fugitive slaves in the wartime capital, was established in a house confiscated from a Treasury Department official who had left Washington to serve in the Confederate government. After the Civil War the Home moved to the Freedmen’s Bureau Subdivision, near Howard University.

Allen Gangewer was one of the founders of the National Colored Home. He started his career as editor of a German newspaper in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In 1851 Gangewer supported the establishment of Myrtilla Miner’s Normal School for Colored Girls in Washington. In 1854 he took charge of an anti-slavery weekly in Ohio. Five years later he became private secretary of Governor Salmon Chase of Ohio. Chase became Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury, and Gangewer got a position in the Treasury.

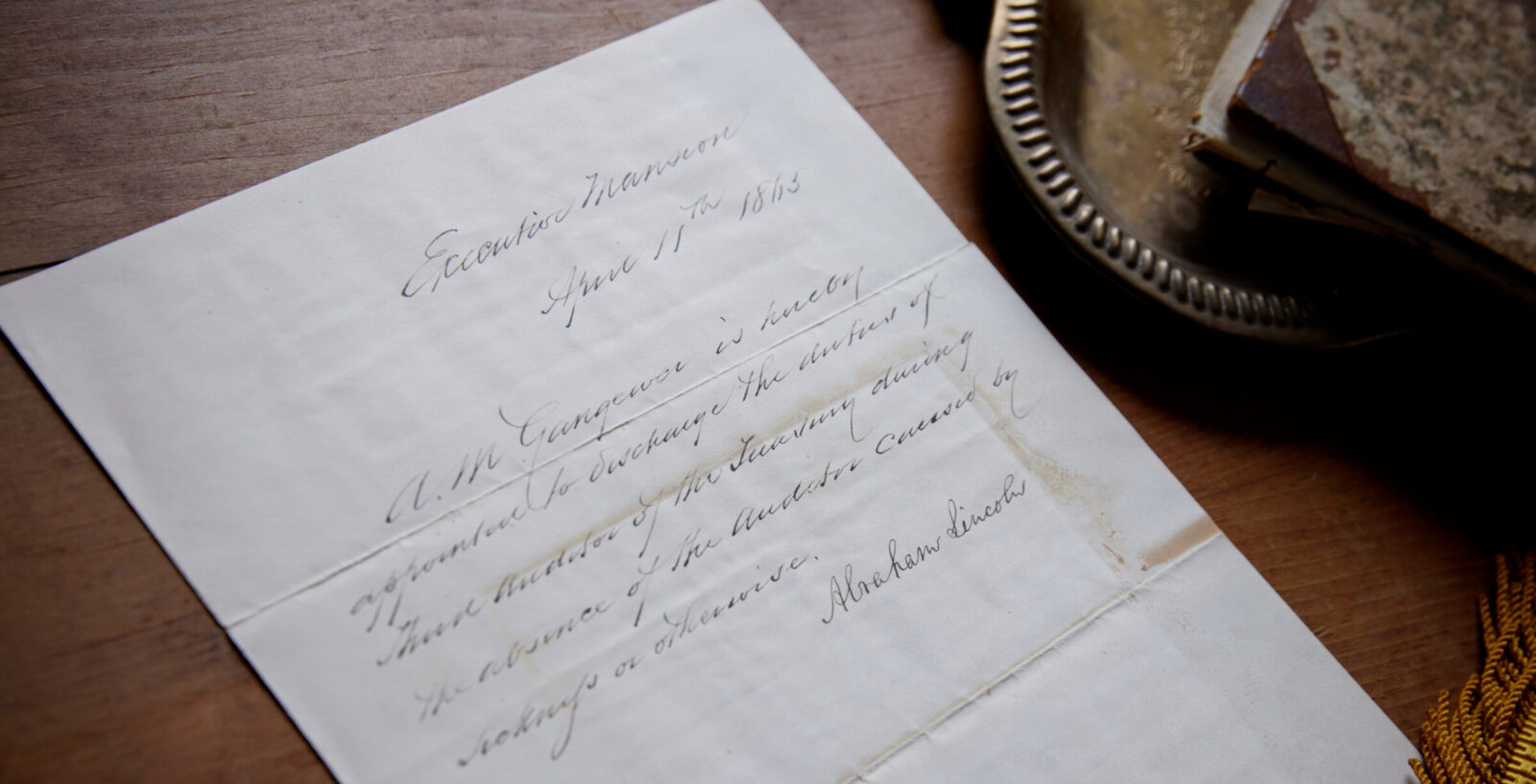

Document signed, Washington, April 11, 1865. “A.M. Gangewere is hereby appointed to discharge the duties of Third Auditor of the Treasury during the absence of the Auditor caused by sickness or otherwise. Abraham Lincoln.”

This is a rare opportunity to own something signed by Lincoln in his last days, and in fact on the day of his last speech to the public.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services