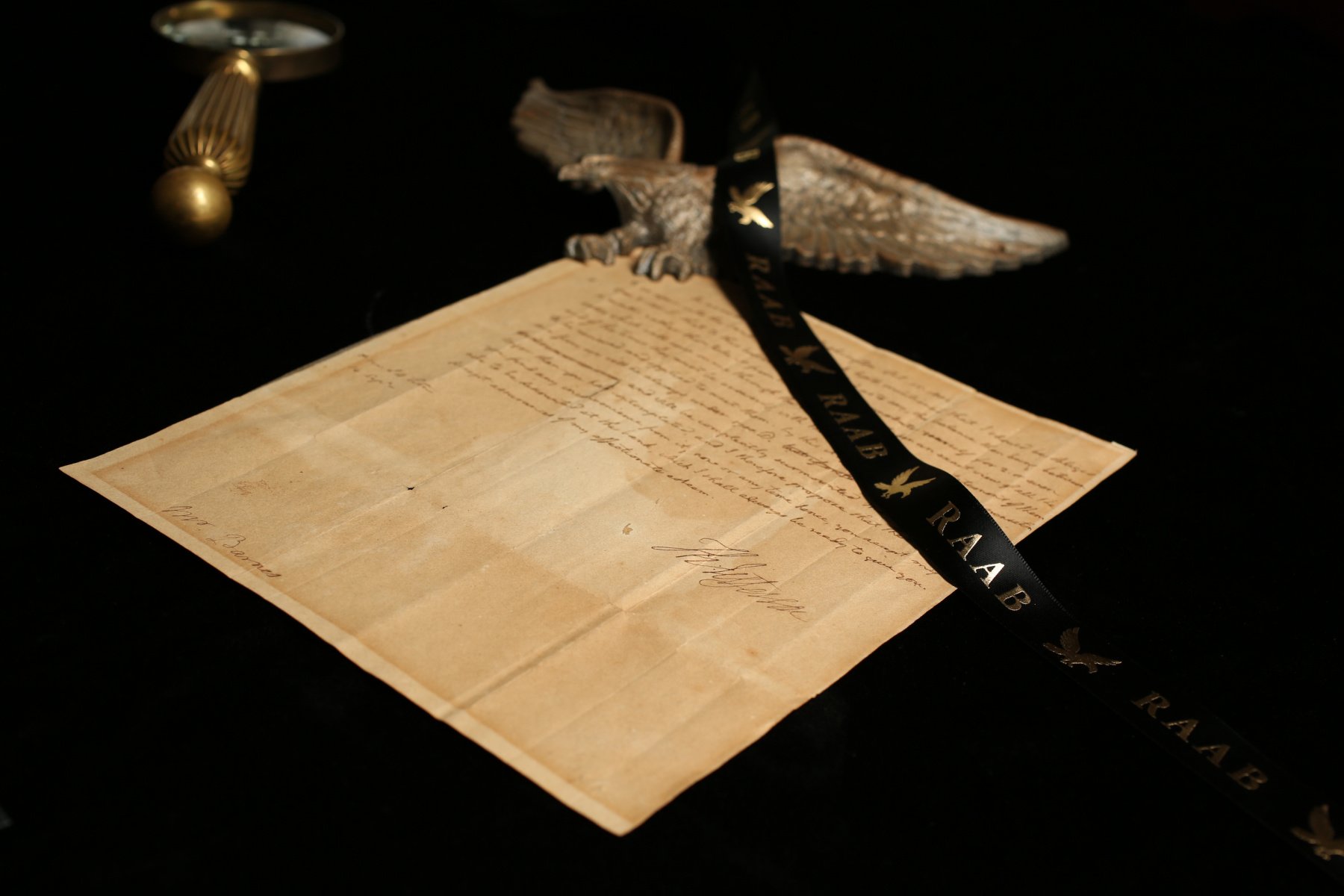

In an Unpublished Letter, President Thomas Jefferson Manages the Expense of his Presidential Household and his Estate in Monticello

He seeks to stretch his funds for months in an attempt to avoid borrowing against future earnings

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

Among the recipients were his servants, chef, coachman, and others, during a time when Meriwether Lewis was living with him

A remarkable letter showing the fragile nature of the former President’s and founding father’s personal financial state and how he juggled funds

This letter, unpublished and whose content was not...

Among the recipients were his servants, chef, coachman, and others, during a time when Meriwether Lewis was living with him

A remarkable letter showing the fragile nature of the former President’s and founding father’s personal financial state and how he juggled funds

This letter, unpublished and whose content was not known till now, was last sold in 1929 through the firm of Thomas Madigan in New York City. It was acquired by us from the heirs of that buyer.

Thomas Jefferson lived with his debt throughout much of his life, inheriting debt from his father and living beyond his means with large projects and lavish lifestyle. Eventually this would lead to the sale of his property and land. And his Presidential salary did little to alleviate this. His personal household expenses were such that he was essentially paying bills paycheck to paycheck, a sharp contrast to how we imagine the personal finances of an American president today.

John Barnes emigrated from England to America about 1760. He was a tea merchant and grocer in New York and Philadelphia, relocating to the latter city when the federal government moved there in 1791. Barnes remained in Philadelphia until 1800, when he moved to Washington to serve as a contractor with the Treasury Department. Jefferson had known him for many years and appointed him customs collector at Georgetown in 1806, a position Barnes held until his death. He was during much of this time also Jefferson’s banker and commission agent, helped him manage the investments of Tadeusz Kosciuszko and William Short, and supplied him with groceries from 1795 until Jefferson’s retirement. Barnes kept his personal house running during his time in Washington at the Presidential Mansion.

In May 1802, Jefferson wrote a letter with dire news of his finances. “I received yesterday your favor of the 10th. and am sincerely concerned at the disappointment at the bank of Columbia [which evidently would not supply him with needed funds]. This proves farther the propriety of my curtailing expenses till I am within the rigorous limits of my own funds, which I will do. in the mean time I must leave to your judgment to marshall our funds for the most pressing demands, till I can be with you.”

In June, Jefferson wrote to Barnes explaining what the main outstanding bills would be that they might trim. These were the prime recurring bills of his household presidency during this time. “Th: Jefferson has been taking a view of his affairs, and sends mr Barnes a statement of them. if it should be possible to get through the month of July without the aid of the bank, by my giving a new note there on the 4th of August for 2000. Doll. we should on that day be almost completely relieved, and the receipt of the 4th. of October will take up the note, and leave me entirely out of debt. Perhaps we may not be able to squeeze down the houshold expenses to 600.

“LeMaire’s bills @ 75. D a week would be 337.

Dougherty’s are per month about 70.

groceries about 120.

servant’s wages 152”

Lemaire was his steward and helped with meal preparation. Doughtery was his coachman and servant. Among the other servants were former slaves, including James Hemings. There were white and free black servants, some remaining for long periods of time and living there or close; others would come and go and performed specific tasks.

Money was also paid for ad hoc expenses and money sent home to Monticello and to his daughter. Jefferson evidently felt that the largest chunk and perhaps where he could trim expenses was his domestic situation.

Interestingly during this time Meriwether Lewis was serving as Jefferson’s secretary and living in the presidential mansion.

He evidently provided that note in late Summer to the bank and hoped that it would last a while, a point on which Barnes evidently had some concern. Jefferson did his own tally and explained the situation to Barnes in this letter, explaining that he calculated it would last him through the winter.

Autograph letter signed, Washington October 15, 1802, to John Barnes. “In answer to my letter which had mentioned that I should be obliged to go again into the bank, you were so kind as to say, the balance then being between $1700 and $1800, that from this balance you could accommodate yourself for 2 or even 4 months rather than take it from the bank. I have taken an exact view of all the calls which will come to me through the winter and send you a statement of them and of the times they must be answered with the immediate sums of compensation to be received and applied to meet them. By this it appears that the balance due from me will always be under $1700 and will be completely surmounted March 4. This is longer than you had contemplated, and I therefore propose that the moment you find any inconvenience from it, now or any time hence, you accept my note to be discounted at the bank, which I shall always be ready to give you. Accept assurance of my affectionate esteem…”

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson notes that “A letter from TJ to Barnes dated 15 Oct. is recorded in SJL but has not been found.”

This letter, unpublished and whose content was not known till now, was last sold in 1929 through the firm of Thomas Madigan in New York City. It was acquired by us from the heirs of that buyer.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services