James A. Garfield Struggles to Hold Together the Union Party Crafted by Lincoln, While Asserting the Power of Congress to Set Reconstruction Policies

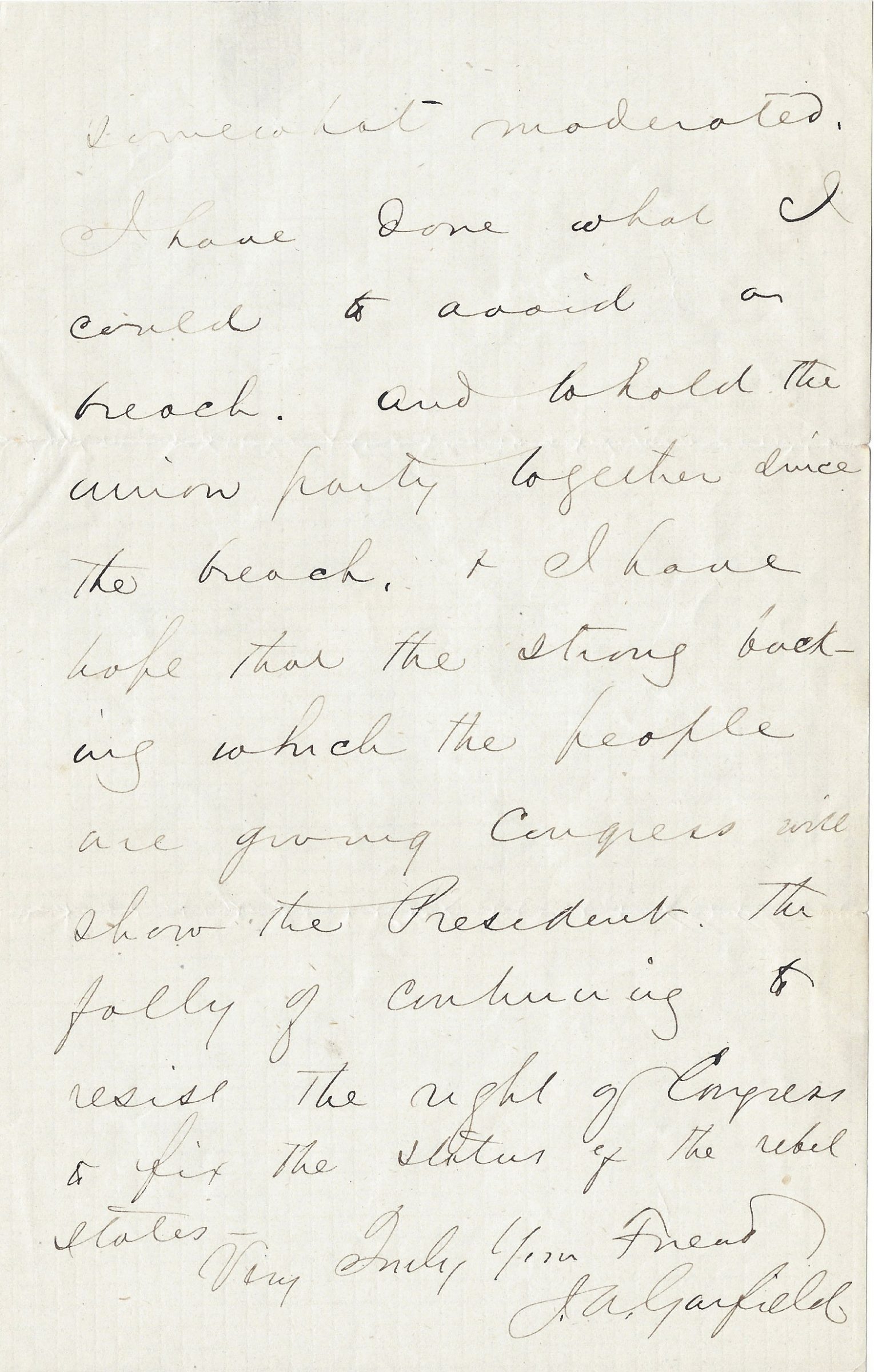

Congress - not President Johnson - has the right “to fix the status of the rebel states,” he writes, adding “I have done what I could to avoid a breach, and to hold the Union Party together amid the breach…”.

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

The Republican party – sectional and coming into power in March 1861 on the single issue of opposition to the extension of slavery – was forced by the secession movement to take up the task of preserving the Union by war. Consequently, the party developed new principles, welcomed the aid of the...

The Republican party – sectional and coming into power in March 1861 on the single issue of opposition to the extension of slavery – was forced by the secession movement to take up the task of preserving the Union by war. Consequently, the party developed new principles, welcomed the aid of the War Democrats, and found it advisable to drop its name and with its allies to form the National Union party. It was this National Union party that in 1864 nominated Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, and Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, on the same ticket. Lincoln’s second Cabinet was composed of both Republicans and War Democrats. When the war ended, the Republican leaders were anxious to hold the Union party, which they essentially dominated, together, but instead found that there was a movement of the War Democrats back to their old party, which if it continued would leave in the Union party only its Republican members. And within those members, the radical leaders, favoring difficult hurdles for Southern states seeking to regain their status in good standing within the nation, predominated.

Though all factions within the South supported the war after it began, the former Whigs and Douglas Democrats – those who had been “Union” men in 1860, when it was over, expected to reorganize in opposition to the extreme Democrats, who were now charged with being responsible for the misfortunes the war had brought their region. The ex-Whigs in particular were in a position to affiliate with the National Union party of the North if proper inducements were offered, while the old-style Democrats were ready to rejoin their old party. But the embittered feelings resulting from the murder of Lincoln and the rapid development of the struggle between President Johnson and Congress caused the radicals to lump the old Union Democrats and Whigs together with the secessionists, and many were driven where they did not want to go, into an affiliation with the Democratic Party. Many went very reluctantly; the old Whigs, indeed, were not firmly committed to the Democrats until radical Reconstruction had actually begun.

Initially President Andrew Johnson, who hated secession and the men who had brought it, was inclined to support the policies of the Radical Republicans to punish the South, and some radical leaders understood that he was in favor of Negro suffrage, the supreme test of radicalism. He was even anxious to arrest the military leaders who had been paroled, and was checked in this desire by General Grant’s firm protest. But quickly, when the excitement caused by the assassination of Lincoln and the break-up of the Confederacy had moderated somewhat, Johnson saw before him a task so great that his desire for violent measures was chilled. He must disband the great armies and bring all war work to an end; he must restore intercourse with the South, which had been blockaded for years; he must for a time police the country, look after the Negroes, and set up a temporary civil government; and finally he must work out a restoration of the Union. Then three influential cabinet advisers – William Seward, Gideon Welles, and Hugh McCulloch – blunted his zeal for inflicting punishments by advising adoption of policies that would make Reconstruction more mild. So Johnson changed his mind and by 1866 was taking measures to carry out a policy of conciliation to Southern whites. This policy soon brought him into contention with the Republicans that controlled Congress. In February 1866 the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau was extended by Congress over a Johnson veto, with the veto message of February 19 stating that the seceded states were now “entitled to enjoy their constitutional rights as members of the Union”. On February 20 and March 2, respectively, the House and Senate objected to that, passing resolutions to the effect that “No Senator or Representative shall be admitted to either branch of Congress from any of the [seceded] states until Congress shall have declared such state entitled to such representation.” The battle between Congress and the President was now joined. In April the 1866 the Civil Rights Act would pass despite Johnson’s veto; and in 1867 the Reconstruction Acts would be passed, all over Johnson’s veto. Impeachment loomed in the near future.

James A. Garfield was a former general who was elected to Congress in 1862. After the war’s end, his policy was to straddle the middle, supporting Republican initiatives while trying to tone them down to create less friction with President Johnson and the South. Perhaps the prime reason Garfield took this stance was because he was trying to save the Union Party that had been crafted by Lincoln, and realized that harsh Reconstruction measures would fragment not merely that party but the country. In the controversy over the Freedmen’s bill, Garfield spoke from the House floor trying to thread the needle by advocating rights for the freed Negroes, while stating his willingness to accept the word of Southern whites, if given, that they would comport themselves as good citizens in the future. These same questions arose in March during the then-ongoing discussions of the Civil Rights Act. In reading the letter below, keep in mind that Garfield was always a strong supporter of tariffs, and in 1866 Congress was considering a tariff bill.

Autograph letter signed, 2 pages, Washington, March 15, 1866, showing Garfield’s efforts to keep the Union Party together, while criticizing Johnson’s Reconstruction policies and supporting the right of Congress to set such policies. The recipient was most likely B. Gratz Brown, a former senator from Missouri who had been elected on a Unionist ticket but had returned home in 1867. He initially supported the Radical Republicans, but in 1866 began moving away from their most extreme positions. Being from a border state, Brown would have wanted preservation of the Union Party. ”My dear Brown, We are at work on a General Tariff bill, but it will be some time before it will be completed. I have no doubt we shall give some relief to the Iron interest, but how much or how soon, I cannot tell. Things are still in a bad shape, though somewhat moderated. I have done what I could to avoid a breach, and to hold the Union Party together amid the breach, & I have hope that the strong backing which the people are giving Congress will show the President the folly of continuing to resist the right of Congress to fix the status of the rebel states. Very Truly Your Friend, J. A. Garfield.”

Garfield clearly saw himself as the great conciliator, and that is how those at the time saw him as well. It was precisely this quality that accounted for his rise to the presidency.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services