The Original, Delivered Manuscript of the Inaugural Address of President Benjamin Harrison

The Reading Copy, identified and signed by him, and obtained by us originally from a direct descendant

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

Our research has failed to turn up even one other delivered manuscript – The Reading Copy – of an Inaugural Address having reached the market.

When George Washington delivered an inaugural address in 1789, he created a precedent that every President has followed since. The address is the first official act...

Our research has failed to turn up even one other delivered manuscript – The Reading Copy – of an Inaugural Address having reached the market.

When George Washington delivered an inaugural address in 1789, he created a precedent that every President has followed since. The address is the first official act of the new President following the swearing in, and sets the tone for his administration. People flock from all over the country to be present when the President lays forth his vision, and in the age of radio and television, untold millions hear or watch the historic moments themselves.

Some inaugural addresses are great speeches still quoted today. Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address famously called for healing a torn nation, saying “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt reanimated faith in a Depression-scarred country, opining “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” And in 1961, John F. Kennedy inspirationally declared, “And so my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” The inaugural address is the embodiment of the President, and his plans and hopes for the future. It is also a great tribute and reaffirmation to our political system.

Today’s inauguration is read from a teleprompter. A manuscript may exist somewhere, but it is a draft. Historically, Presidents held paper speeches. Some of these “reading copies,” the actual speeches held and read by the Presidents during the address, still survive. The Franklin Roosevelt Museum and Library has his. Abraham Lincoln’s is at the Library of Congress. So is the one delivered by Thomas Jefferson. The National Archives, which also is the umbrella for the many Presidential libraries, has John Kennedy’s reading copy. Our research did not disclose a surviving reading copy not in an institution.

President Benjamin Harrison and a Political Dynasty

The Harrison family is a political dynasty. For generations, from the dawn of our country until the 20th century, its members served the public good, long before the Kennedys or the Bushes or Roosevelts. Two Harrisons were President. Benjamin Harrison was the great-grandson of Declaration of Independence signer Benjamin Harrison, the grandson of President William Henry Harrison, and son of Congressman John Scott Harrison. During the Civil War, Benjamin was a Colonel commanding the 70th Indiana Regiment, which served with Sherman in the Atlanta campaign and participated in the major battles there. In the midst of that campaign he was promoted to command a brigade in the 20th Corps. Late in 1864 the unit was transferred to Gen. George Thomas’ army and fought at Nashville. After the war Harrison returned to Indiana to practice law, and being from a prominent political family, soon became involved in Republican politics. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1880 and served in that body from 1881-1887. During his term Harrison was a prominent spokesperson for his party, supporting high tariffs to bring in revenue, and advocating spending the money on internal improvements to expand American business and industry, and generous pensions for veterans and their widows. Believing that education was necessary to help the black population rise to political and economic equality with whites, he supported aid for education. And bucking his party, he opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act. He showed real courage at that time in standing up for both black and Chinese Americans, when it was anything but popular to do so.

When the Republican National Convention opened on June 19, 1888, there were twelve potential nominees for president, including Harrison. The initial favorite for the nomination was the previous nominee, James G. Blaine of Maine, who had come close to defeating Grover Cleveland in 1884. After Blaine wrote letters denying any interest in the nomination (perhaps coyly trying to generate a clamor for him to reconsider), his supporters took him at his word and divided among other candidates, with John Sherman of Ohio the leader among them. Harrison placed fourth on the first ballot, with Sherman in the lead, and the next few ballots showed little change. However, the Blaine supporters shifted their support around among the candidates, until finding in Harrison the most acceptable alternative. Benjamin Harrison was nominated on the eighth ballot by a 544 to 108 vote, becoming the Republican presidential nominee.

The Inauguration

It was raining on Inauguration day, March 4, 1889. Outgoing President Grover Cleveland held an umbrella over Harrison’s head as he took the oath of office. The book Benjamin Harrison: Centennial President by Anne Chieko and Hester Moore describes the scene at the inauguration. “Standing beside Chief Justice Melville Fuller, Benjamin Harrison removed his silk top hat and placed his right hand on selected pages of his open black leather bound Holy Bible held by the court clerk. The ritual was documented in the Bible at Psalm 121:1-6 [‘I lift up my eyes to the hills – where does my help come from? My help comes from the Lord, the Maker of heaven and earth’], where Harrison wrote in pencil ‘My hand was here when the oath was administered. B.H.’ He repeated the oath…Benjamin Harrison was thus inaugurated the 23rd President of the United States. Then he donned his silk hat and pulled a manuscript from his pocket that had been typed by his secretary Elijah Halford. Adjusting his spectacles, the President delivered his speech with sincere eloquence. He called for effort to preserve a more perfect union, advocating early statehood for territories, universal education, protectionism, pensions for dependents of Civil War veterans, and increased patriotism. He expressed his concern for Negro voting rights, called for justice against trusts and monopolies, and stated the necessity for a strong navy…The inaugural speech was praised as a document of literary as well as political merit. When the speech was concluded, Harrison turned and kissed his wife and daughter.”

The Inaugural Manuscript

The Library of Congress has three drafts of Harrison’s inaugural address. The final, typed, and delivered manuscript was handed down from generation to generation in the Harrison family and was unknown.

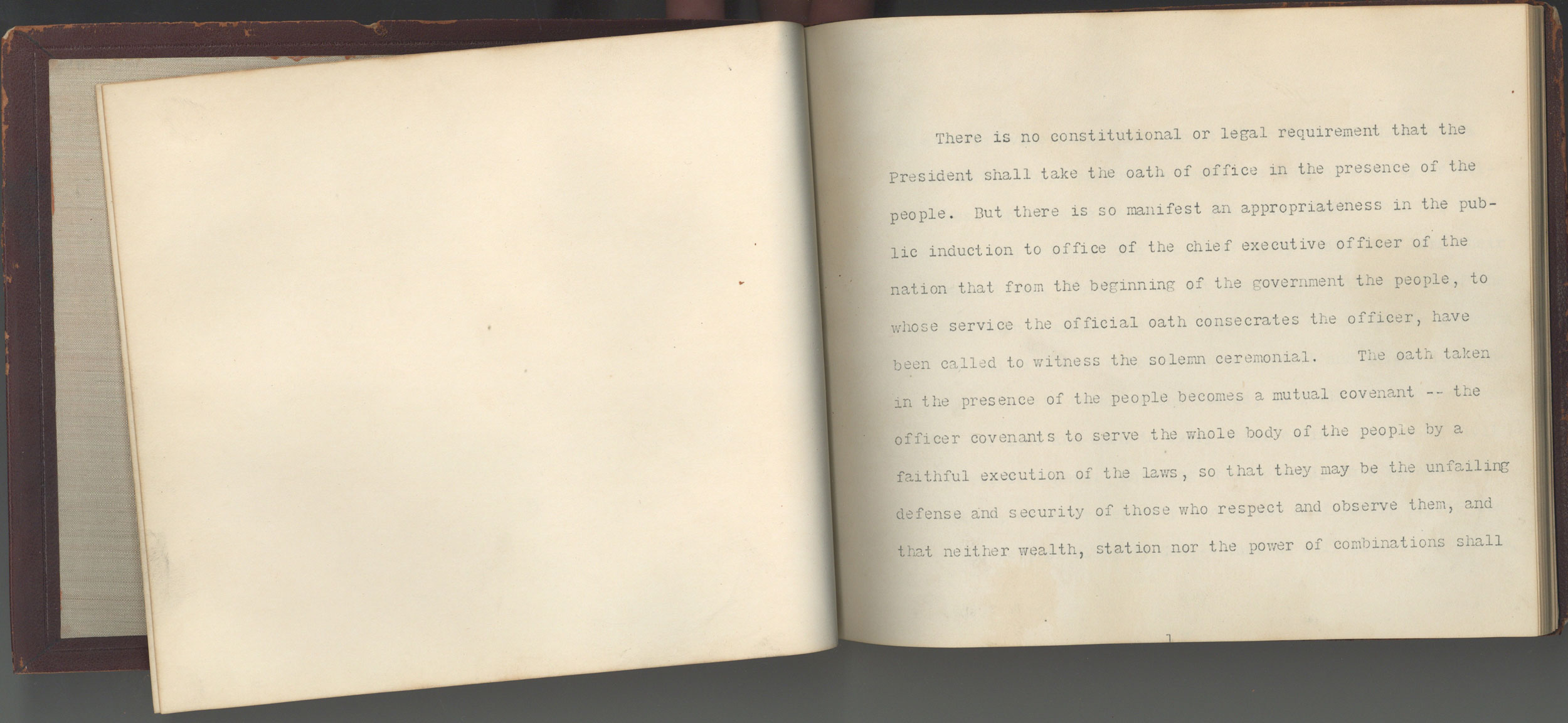

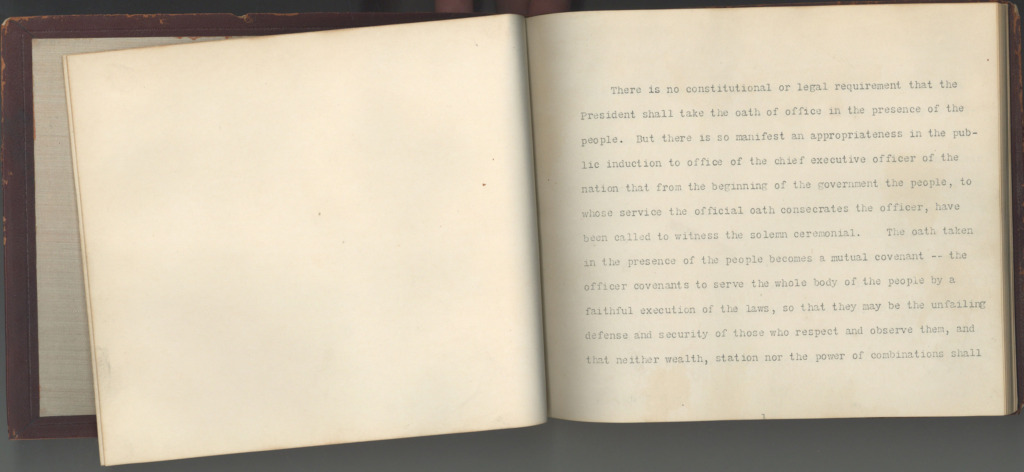

Document signed, March 4, 1889, Harrison’s reading copy of his inaugural address. It is 37 small-numbered, single-sided pages on medium-heavy woven paper with the “Fairfield Superfine” watermark. And just as Harrison annotated the Bible he used after taking the oath of office, at the end of this speech he has written “This is the MSS (manuscript) used by me in delivering the address March 4, 1889.” Considering his practice was to so annotate documents immediately after the event, we assume this was done right after the address. That would make it the first Harrison autograph as President. Harrison had the sheets bound in a small book. The manuscript is fresh and bright, in excellent condition.

Harrison began his address by noting that there is no Constitutional requirement that presidents give an inaugural address, yet they do it as it creates a “mutual covenant” with the American people, in fact with the “whole body of the people”.

On civil rights he asked rhetorically, “Shall the prejudices and paralysis of slavery continue to hang upon the skirts of progress?” He pronounced that the passions of the Civil War had by now been laid to rest. And he concluded powerfully: “I do not mistrust the future. Dangers have been in frequent ambush along our path, but we have uncovered and vanquished them all. Passion has swept some of our communities, but only to give us a new demonstration that the great body of our people are stable, patriotic, and law-abiding. No political party can long pursue advantage at the expense of public honor…The peaceful agencies of commerce are more fully revealing the necessary unity of all our communities, and the increasing intercourse of our people is promoting mutual respect…Each State will bring its generous contribution to the great aggregate of the nation’s increase. And when the harvests from the fields, the cattle from the hills, and the ores of the earth shall have been weighed, counted, and valued, we will turn from them all to crown with the highest honor the State that has most promoted education, virtue, justice, and patriotism among its people.”

Historian Robert McNamara calls Harrison’s one of the five best Inaugural Addresses of the 19th Century. He notes that 19th century Inaugural Addresses were generally “collections of platitudes and patriotic bombast”, and singles out Harrison’s and four others that were not. He continues that, taking office at a time when the United States was enjoying progress and wasn’t facing any great crisis, Harrison chose to deliver a history lesson and present a vision to the nation. He adds that Harrison was prompted to do so because his inauguration marked the centennial of George Washington’s first inauguration in 1789, a fact mentioned in the address. Ex-President Rutherford B. Hayes was even more laudatory, writing Harrison the day after the address, “Jefferson and Lincoln, by a long distance, excel all others in their inaugural addresses. Yours will take rank with theirs. ‘It is all golden.’”

Provenance

Harrison’s son, Russell Benjamin Harrison, attended the Republican National Convention on his father’s behalf, and stood at his father’s right hand side when he was officially notified of his nomination for president. Russell was present with the family on election night 1888 to share in the excitement, and with his father headed the reception committee for the open house held by the President-elect at his home in Indianapolis on New Year’s Day 1889, which 2,000 people attended. Russell, with his wife Mary, were on the uncovered inaugural stand, along with the Harrison family and her mother. Mrs. Russell Harrison was the daughter of Nebraska Territorial Governor and U.S. Senator Alvin Saunders. This manuscript descended from President Benjamin Harrison to Russell and Mary Saunders Harrison; from them to a living descendent; and from that descendent to The Raab Collection, along with other Harrison and Saunders family historical artifacts.

History of Inaugural addresses on the Market

Our research has failed to turn up even one other delivered manuscript – The Reading Copy – of an Inaugural Address having reached the market. Some presidents signed souvenir copies or excerpts produced years after the Addresses were given. Our research disclosed no comparables to the Harrison Reading Copy. These are the closest pieces we have found, though none are reading copies. Unsigned manuscript fragments of George Washington’s undelivered first inaugural address occasionally reach the market and bring six figures. A 13-page manuscript of an early draft of James Monroe’s first Inaugural Address, differing from the final, sold in 1993 for $350,000. And from time to time, one sees souvenir copies or excerpts of addresses, sometimes in manuscript form but generally imprints of typescripts prepared by collectors and sent for signature, usually produced years after the addresses were given.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services