Lieut. General Ulysses S. Grant Arranges a Meeting to Plan the Assault on Wilmington, NC, the Last Confederate Seaport Open to Blockade Runners

Taking Wilmington will cut off Confederate supplies and also be of assistance to Maj. General William T. Sherman, as he moved north from Georgia

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

After the fall of Mobile, Alabama, in August 1864, Wilmington, North Carolina, became the last major Confederate seaport open to blockade-running traffic. Throughout the war, Wilmington had thrived as a hub for Southern maritime trade. Despite a vigilant Union naval blockade, profit-minded traders successfully smuggled foreign goods and munitions of war into...

After the fall of Mobile, Alabama, in August 1864, Wilmington, North Carolina, became the last major Confederate seaport open to blockade-running traffic. Throughout the war, Wilmington had thrived as a hub for Southern maritime trade. Despite a vigilant Union naval blockade, profit-minded traders successfully smuggled foreign goods and munitions of war into Wilmington.

By late summer 1864, Union policy makers began to focus their attention on the “city by the sea.” In assessing Wilmington’s illicit trade and the link to Lee’s army, U.S. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles deemed Wilmington “more important, practically” than the capture of the Confederate capital at Richmond. Welles pushed for a combined army-navy strike to topple Wilmington and the vast network of river defenses guarding her estuary.

The key to these defenses was Fort Fisher — the largest earthen fort in the Confederacy. Commanded by Col. William Lamb, the massive 47-gun bastion protected New Inlet at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, twenty miles below the docks at Wilmington. Fisher communicated with incoming blockade-runners through a system of signal lights, and her guns dueled with Union blockaders on a regular basis. Secretary Welles understood that Fisher had to be captured in order to choke Lee’s supply line. President Abraham Lincoln and Union general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant agreed.

As Grant wrote, “Up to January, 1865, the enemy occupied Fort Fisher, at the mouth of Cape Fear River and below the City of Wilmington. This port was of immense importance to the Confederates, because it formed their principal inlet for blockade runners by means of which they brought in from abroad such supplies and munitions of war as they could not produce at home. It was equally important to us to get possession of it, not only because it was desirable to cut off their supplies so as to insure a speedy termination of the war, but also because foreign governments, particularly the British Government, were constantly threatening that unless ours could maintain the blockade of that coast they should cease to recognize any blockade. For these reasons I determined, with the concurrence of the Navy Department, in December, to send an expedition against Fort Fisher for the purpose of capturing it.”

So Grant sent an expedition to Cape Fear in January 1865. This time, the commander of army ground forces was Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry. With 58 warships, Admiral David D. Porter’s armada hurled another 20,000 projectiles onto Fort Fisher. Terry’s infantry and a naval shore contingent stormed the mighty bastion. After a savage hand-to-hand engagement, the Confederate garrison surrendered on the night of January 15. This was a major Union victory, without which the hope of taking Wilmington would be illusory. But Wilmington was still in Confederate hands, so the Confederates still had hopes of using this key port for supplies and to combat Union naval plans in the area.

After Sherman took Savanah in December 1864, he suggested the idea then of marching up north through the Carolinas, joining with Grant, and destroying Confederates resources on the way. Grant agreed, writing “if successful, it promised every advantage. His march through Georgia had thoroughly destroyed all lines of transportation in that State, and had completely cut the enemy off from all sources of supply to the west of it. If North and South Carolina were rendered helpless so far as capacity for feeding Lee’s army was concerned, the Confederate garrison at Richmond would be reduced in territory from which to draw supplies, to very narrow limits in the State of Virginia; and, although that section of the country was fertile, it was already well exhausted of both forage and food. I approved Sherman’s suggestion therefore at once.” Sherman’s army’s move would need both naval and land support, and Wilmington could be a thorn in his side.

To speed the collapse of the faltering South, and eliminate Wilmington as a threat, Grant gathered forces in the sea off Wilmington. On January 28, 1865, Grant himself came down to confer with Admiral Porter, his old Vicksburg shipmate and hero of Fort Fisher. Grant spent several hours on board the flagship Malvern where plans took shape for the push into North Carolina up the Cape Fear River as Sherman marched inland parallel to the coast. When Grant returned to City Point, Virginia he quickly dispatched General Schofield by sea with an army which, with the big guns of the fleet, would be large enough to push on to Wilmington.

Gustavus Fox was Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Fox enjoyed Lincoln’s confidence, and the two consulted often, both at the White House and at the Navy Department where Lincoln was a frequent visitor. He was a prime advocate of the use of ironclads like the Monitor. He was involved in setting up and coordinating Grant’s trip to Porter and would attend the meeting as well.

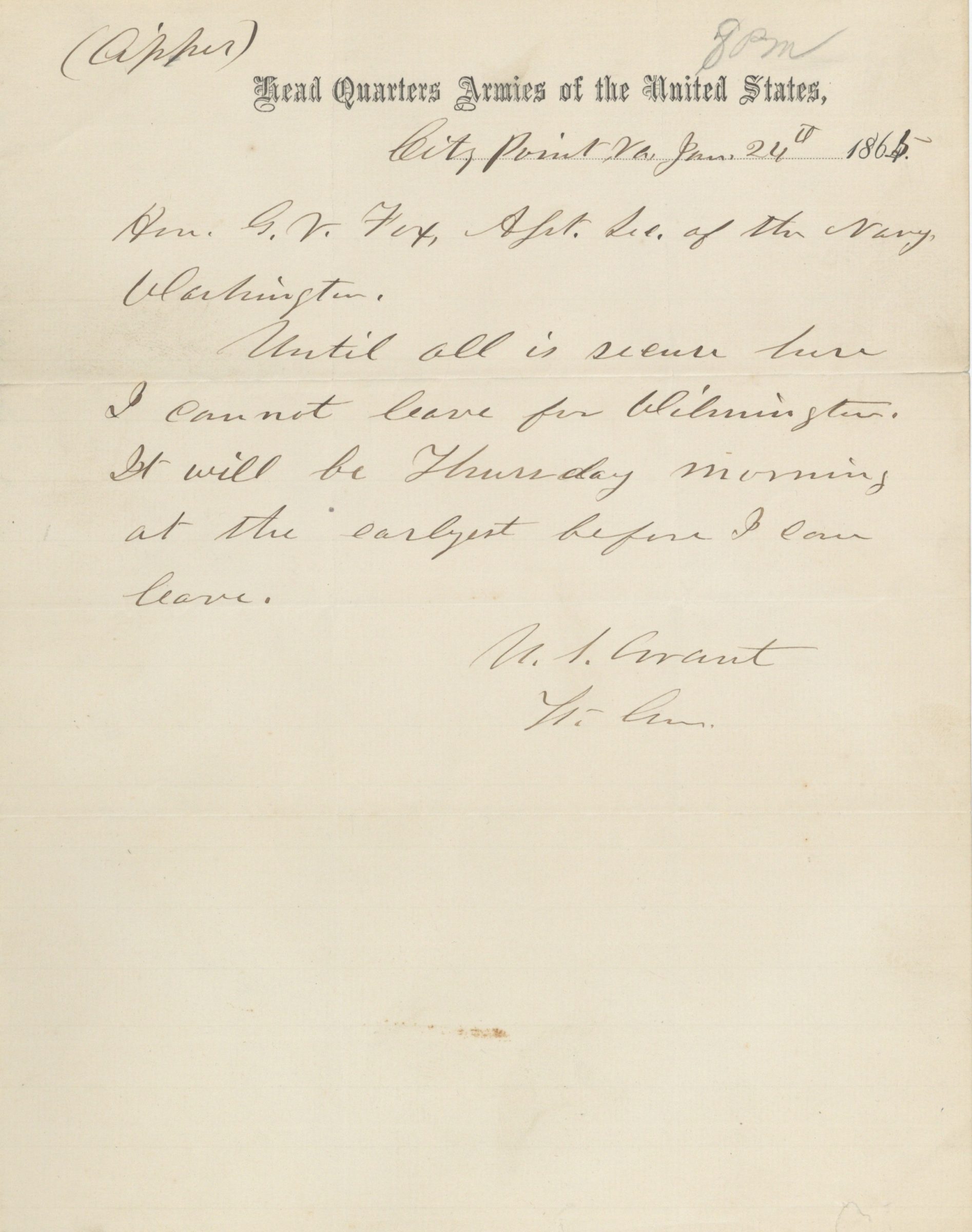

On January 24, 1865, Fox telegraphed Grant that a steamer had been sent for to take him to Porter. Grant responded, informing Fox of his schedule. Autograph letter signed, on his Head Quarters of the United States letterhead, City Point, 8 pm, Tuesday, January 24, 1865, to Fox. “Until all is secure here, I cannot leave for Wilmington. It will be Thursday morning at the earliest before I can leave.” The short delay was likely caused by Grant’s changing leadership of the James River Flotilla and his attempt to get a promotion for Gen. George G. Meade. The meeting with Porter took place on January 28, just four days later.

Plans in place, now was the time to attack Wilmington. In a three-pronged offensive, Union troops advanced up the east and west banks of the Cape Fear River, with Admiral Porter’s shallow-draft gunboats bringing up the center. After engagements at Sugar Loaf, Fort Anderson, and Forks Road, Union forces occupied Wilmington on February 22, 1865. The Confederacy was now fully blockaded, with no reliable access to the sea.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services