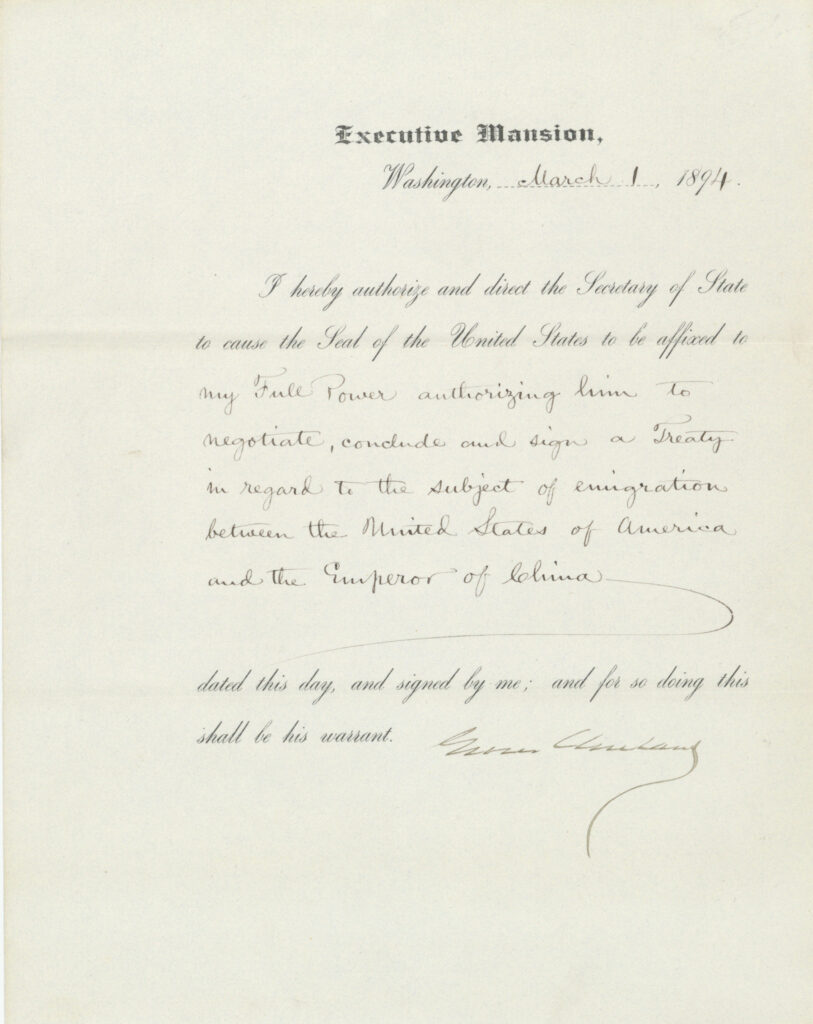

President Cleveland Authorizes the Negotiation of a Treaty Limiting Chinese Immigration to the United States

The authorization states the subject of the treaty as “emigration between the United States of America and the Emperor of China”, an act elicited in large part by the Chinese immigration during the California Gold Rush

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

A very rare document relating to U.S./Chinese relations and the exclusions of Chinese immigrants

In the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to the United States, first to work in the gold mines, but also to take agricultural jobs, and factory work, especially in the garment industry. Chinese immigrants were particularly instrumental in building...

A very rare document relating to U.S./Chinese relations and the exclusions of Chinese immigrants

In the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to the United States, first to work in the gold mines, but also to take agricultural jobs, and factory work, especially in the garment industry. Chinese immigrants were particularly instrumental in building railroads in the American west, and as Chinese laborers grew successful in the United States, a number of them became entrepreneurs in their own right. As the numbers of Chinese laborers increased, so did the strength of anti-Chinese sentiment among other workers in the American economy. This finally resulted in legislation that aimed to severely limit future immigration of Chinese workers to the United States,.

American objections to Chinese immigration took many forms, and generally stemmed from economic and cultural tensions, as well as ethnic discrimination. Most Chinese laborers who came to the United States did so in order to send money back to China to support their families there. At the same time, they also had to repay loans to the Chinese merchants who paid their passage to America. These financial pressures left them little choice but to work for whatever wages they could. Non-Chinese laborers often required much higher wages to support their wives and children in the United States, and also generally had a stronger political standing to bargain for higher wages. Therefore many of the non-Chinese workers in the United States came to resent the Chinese laborers, who might squeeze them out of their jobs. Furthermore, as with most immigrant communities, many Chinese settled in their own neighborhoods, and tales spread of Chinatowns as places where large numbers of Chinese men congregated to smoke opium or gamble. Some advocates of anti-Chinese legislation therefore argued that admitting Chinese into the United States lowered the cultural and moral standards of American society. Others used a more overtly racist argument for limiting immigration from East Asia, and expressed concern about the integrity of American racial composition.

To address these rising social tensions, from the 1850s through the 1870s the California state government passed a series of measures aimed at Chinese residents, ranging from requiring special licenses for Chinese businesses or workers to preventing naturalization. Because anti-Chinese discrimination and efforts to stop Chinese immigration violated the 1868 Burlingame-Seward Treaty with China, the federal government was able to negate much of this legislation. In 1880, the Hayes Administration appointed U.S. diplomat James Angell to negotiate a new treaty with China. The resulting Angell Treaty permitted the United States to restrict, but not completely prohibit, Chinese immigration. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for a period of 10 years. The Act also required every Chinese person traveling in or out of the country to carry a certificate identifying his or her status as a laborer, scholar, diplomat, or merchant. The 1882 Act was the first in American history to place broad restrictions on immigration.

In 1888, Congress took exclusion even further and passed the Scott Act, which made reentry to the United States after a visit to China impossible, even for long-term legal residents. The Chinese Government considered this act a direct insult, but was unable to prevent its passage. In 1892, Congress voted to renew exclusion for ten years in the new Geary Act, that extended the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 by adding onerous new requirements.

But the United States wanted even more, and in 1894 President Cleveland authorized the Secretary of State to negotiate another treaty – to be known as the Gresham-Yang Treaty. This treaty was successfully negotiated, and later that year the Gresham-Yang Treaty was signed between the United States and China, in which the Chinese Qing dynasty consented to measures put in place by the United States prohibiting Chinese immigration in exchange for the readmission of previous Chinese residents, thus in effect agreeing to the enforcement of the Geary Act. This was the first time the United States government barred an entire ethnic group from entering the mainland United States. However, despite signing the Gresham-Yang Treaty, the Chinese government held many grievances against the United States related to the various “exclusion laws” passed, and the manner under which they were being enforced.

Document signed as president, Washington, March 1, 1894, being Cleveland’s original authorization to seek what became the Gresham-Yang Treaty. In it, President Cleveland directs the Secretary of State to “cause the Seal of the United States to be affixed to my Full Power authorizing him to negotiate, conclude and sign a Treaty in regard to the subject of emigration between the United States of America and the Emperor of China.”

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services