Sold – Peter The Great Orders the Raids That Led to Victory in the Great Northern War

Russia Emerges as a Great Power.

Peter the Great, Tsar from 1682 until his death in 1725, brought Russia out of feudalism and made it a great empire, one rivaling its neighbors to the West in Europe and the East and South in Asia. The key to this rise to power was a great struggle for control over...

Peter the Great, Tsar from 1682 until his death in 1725, brought Russia out of feudalism and made it a great empire, one rivaling its neighbors to the West in Europe and the East and South in Asia. The key to this rise to power was a great struggle for control over Russia’s only potential access to the sea – the Baltic – without which its military reach and hopes for growth would be limited. The struggle for that access was the Great Northern War.

Virtually every European power played a role in networks of diplomatic and military alliances built around the two principle enemies: Sweden and Russia, under Charles XII and Peter the Great respectively. Sweden had gained the upper hand in the 17th century, taking away Russia’s access to the Baltic Sea and beginning a century of Russian efforts to regain the territory.

By 1700, Peter had built alliances with several countries, including Denmark and Saxony-Poland, and had begun waging the Great Northern War. By 1719, the Swedes had been weakened by a failed invasion of the Russian mainland, defeats of their once-heralded navy, successful though limited sieges by Russia in Scandinavia, and the death of King Charles. However, the war continued and Russia was unable to win a definitive victory.

Swedish strategy in 1719 shifted from outright military victory on the battlefield to negotiating treaties with every nation but Russia, thereby isolating her from her former allies. In June, Sweden signed an armistice with Denmark, now weary of war and happy to achieve territorial concessions. It initiated truce talks with Saxony, England and Hanover.

The Great Raids

On August 13, Russia invaded Sweden and at the Battle of Staket was famously repulsed in a conflict still celebrated today in Sweden. This was a failure for Peter the Great and story of heroism for the Swedes.

Sweden’s new strategy to isolate Russia seemed to be bearing fruit. It made peace with England and Hanover in a treaty that would not be signed in Stockholm until November 9. England – Sweden thought – would be a convenient and distant port to safely harbor its navy. However, by October 11, word of the treaty plans leaked to Peter, and in this apparent diplomatic defeat he saw an extraordinary opportunity. He would use the alliance with England to undermine Swedish public confidence in the effectiveness of its shaken military and the utility of the English friendship by attacking the Swedish coast while its navy was divided. By ordering a series of raids on the Swedish homeland and lifeline – its coast – Peter would make the Swedes see that their war was lost.

General Mikhail Golitsyn, from one of the noblest princely houses of Russia, was one of the foremost Russian generals and military figures of his age. In 1714, he was made Governor of newly conquered Finland and in 1719 controlled the forces that would sweep across the sea and attack the Swedish port towns.

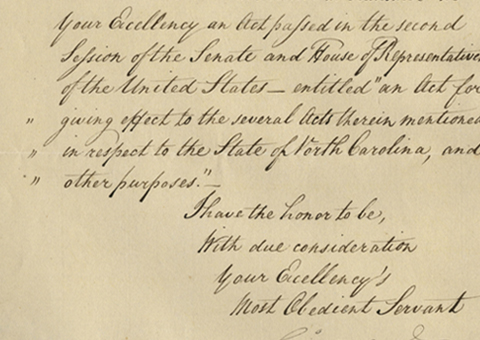

Letter signed, in Russian, Schlusselburg, October 11, 1719, to Golitsyn. “Through your lieutenant, I have received your letters and tables, according to which we will make corrections, and we will let you know what we have done. You also write that should [the Aland waters] freeze, we should send out…some raiding parties. To that I reply that it is imperative to carry this out, because now the Swedish ministers are luring their people on with the fact that they have made peace with the English king, thus giving them hope that we will no longer be free to devastate them, and that peace is useful to them, as it will constrain us; but now have learned that [Loris] is going with his fleet to spend the winter in England, and that is the first thing that will make the Swedes worry that they have been abandoned, and when, with help…this winter, if the job is done by the raiding parties, there will be great unrest among the people, and they will see that their ministers have sold them out again, because the peace will be useless to them.

Just be careful with this…it freezes all winter there, and there’s no great army there, and for that reason, be careful crossing the Aland. In my opinion, we shouldn’t send any Cossacks across so that it won’t bring the enemy any pride if some downfall should come to the regulars. We have the capability to send dragoons; just proceed with caution. Otherwise, we trust your good skill to carry it out as far as possible in order to accomplish something this winter and by that to show the Swedes that we disregard English threats.”

This letter to his commander shows Peter’s thought process, clear purpose, leadership abilities, and military and diplomatic skills and strategies. He specifically relates why he ordered the raids, discusses the Swedish alliance with England and its advantages to Russia, outlines tactics in attacking Sweden, and gives his strategy of implementing his plans.

Per Peter’s instructions in this letter, between 1719 and 1721, the Russian fleet began to ravage the Swedish coast, and by th end had brought that country to its knees. A British fleet arrived in 1720 to aid the Swedes but it did not stem the tide of the war, which had shifted irrevocably in favor of the Russians. In 1721, Sweden pleaded for peace, ceding extensive territory to Russia and relinquishing its role as a major military power.

This is the letter that began the raids that ended the Great Northern War. As William C. Fuller writes in Strategy and Power in Russia, “It was the buildup of Russian naval strength in the Baltic Sea, leading to the enormous amphibious attacks of 1719-1721, that finally brought Sweden to its knees.”

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services