From the Great English Library at Bury St. Edmunds at Its Height, a Surviving 12th Century Fragment, One of Just a Handful of These Manuscripts We Could Find from this Renowned Middle Ages Center Outside an Institution

This leaf, from St. Augustine’s City of God, almost certainly formed part of the library of Nicholas Bacon, Keeper of the Seal of Queen Elizabeth I and father to Francis Bacon, who may have inherited it

It is one of just handful of manuscripts from Bury we found ever having reached the market and in private hands

The Abbey’s location as a place of national importance was secured in 1214, shortly after the creation of this manuscript, when, on St Edmund’s Day, a group of Barons secretly...

It is one of just handful of manuscripts from Bury we found ever having reached the market and in private hands

The Abbey’s location as a place of national importance was secured in 1214, shortly after the creation of this manuscript, when, on St Edmund’s Day, a group of Barons secretly met in this very Abbey and swore an oath to compel King John to accept The Charter of Liberties, which would become the Magna Carta.

Our gratitude to a variety of scholars, in particular Rod Thomson, author of The Library of Bury St Edmunds, for their guidance in research

In 1517, Martin Luther wrote his 95 theses in Germany, and the Protestant Reformation was underway. England’s participation in the Protestant Revolution is best seen through the actions of King Henry the VIII, famed for his six wives and establishment of the Church of England. Between 1536 through 1541, Henry dissolved the medieval monastic houses, friaries, and other religious establishments in England, Ireland, and Wales. This was a large-scale power- and money-grab which amounted in the forced abandonment of buildings and property. Some abbeys, such as Canterbury and Rochester, were allowed to continue as secular cathedrals. However most fell into decay and ruin. If you have seen the 19th century depictions of ruined abbeys in the English countryside from Gothic novels, this was the direct effect of the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Before Henry, these religious establishments were seats of great wealth. Often the monks worked cottage industries, such as manuscript production, beer brewing, honey cultivating, and cheese selling, alongside their holy duties (giving some monastic orders the reputation of being luxurious and decadent with all the cheese, honey, and beer freely flowing). Nobles would die and leave their local cathedral or monastery great riches of currency, art, and objects.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries shattered these institutions, scattering their important possessions far afield, or, worse, seeing the iconoclasm— the destruction— of art such as stained glass, carved altar pieces, and, of course, the beautiful and painstakingly created manuscript books.

The Great Library and Scriptorium at Bury St. Edmunds

The site of the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, located about 75 miles northwest of London in Suffolk, had been used for Christian religious worship since the 7th century. The area gained importance when, in the 10th century, it received the relics of the Anglo-Saxon King Edmund I (from which its current toponym derives). King Canute granted the lands to the monks who were charged with guarding the relics in the 11th century, and by the end of that century, the cult of St Edmund— those who venerated the saint— greatly enriched the new-found Abbey. During the 12th century, the Abbey was enlarged, becoming one of the largest in England. Lands and rights also continued to grow and by the early 14th century, the Abbey owned the entire district of West Suffolk. The monks were allowed to charge tariffs and run the Royal Mint.

The Abbey housed a well-known scriptorium, a center of thought and scholarship in England during the late Middle Ages, in which the monks produced luxurious manuscripts to be studied in the Abbey or loaned out to other religious establishments. Early in its development, from about 1000-1050, the scriptorium primarily copied Latin and Greek patristics, or the works of Church Fathers. During this time, incomplete historic inventories tell us that they copied 65 manuscripts containing the works of St Augustine. The scriptorium flourished under Abbot Anselm between 1125 and 1150— the period during which the present document was created. Concurrent with the scriptorium’s apogee during the “12th century Renaissance”, the texts studied in the very earliest incarnations of universities began to flow from the hands of the Bury St Edmunds scribe-monks. The works reflected more of the content of Continental collections, such as those used at the University of Paris, than those which would have been used at Oxford at the time. As Professor Rod Thomson puts it, “The impression is gained that Bury had, by the middle of the [12th] century, earned a substantial reputation as a possessor and producer of fine books.”

On the City of God Against the Pagans (Latin: De civitate Dei contra paganos), often called The City of God, is a book of Christian philosophy written in Latin by Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD. The book was in response to allegations that Christianity brought about the decline of Rome and is considered one of Augustine’s most important works. As a work of one of the most influential Church Fathers, The City of God is a cornerstone of Western thought, expounding on many profound questions of theology, such as the suffering of the righteous, the existence of evil, the conflict between free will and divine omniscience, and the doctrine of original sin.

Most English monastic houses were unable to come by the Continental exemplars required to copy the works of the Church Fathers. Bury St Edmunds however, benefited from Abbot Anselm and other Continental-connected members of the Abbey who were able to foster this intellectual growth.

As the Middle Ages waxed and wained, the Abbey’s collection of books became large and important. When King Henry the VIII called for the possessions of the monasteries to be recalled into his coffers or destroyed, the Abbey ceded 5,000 marks worth of gold and jewels and was divested of the shrine to St. Edmunds. In November of 1539, the final blow to the Abbey was struck, and all of its gold and precious stones came into the hands of the King to fund his military campaigns. Even the stones of the Abbey were eventually hauled off by builders to create new structures.

The Benedictine Abbey of Bury St Edmunds was one of the wealthiest monastic communities in medieval England, and also formed something of a cultural hub – hence had a large library. Much of that still survives, with N.R. Ker listing 256 mss surviving in various institutions from the house, plus approx another 20 in the more recent supplement to that work (Medieval Libraries of Great Britain, 1941 and Supplement of 1987), of which only 5 are in the US.

In the US, known examples are:

These are:

New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, Univ. of Columbia, Huntingdon Library

The location of the remaining manuscripts is unknown. It has been decades since another Bury manuscript has reached the market.

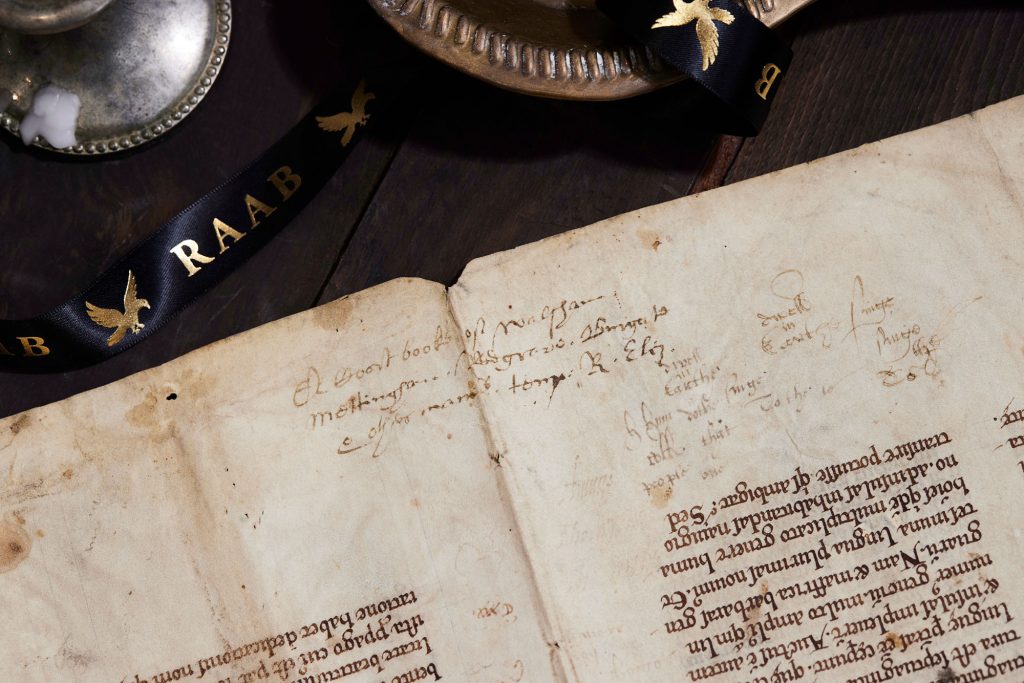

Medieval manuscript, The City of God, two leaves joined together forming one large leaf measuring approximately 15 x 10 inches; in the hand of Scribe A (whose hand has been deciphered and categorized by Parker McLachlan’s definitive work on the subject).

So how did this piece survive?

Sir Nicholas Bacon was a high official in the government of Queen Elizabeth I and father of the renowned philosopher Francis Bacon. Admitted to the bar in 1533, Bacon was made attorney of the court of wards and liveries in 1546. He worked both for the Queen and also Henry VIII. Upon the accession of Elizabeth, Bacon was made lord keeper of the great seal.

16th century notations put the leaf at Waltham, Mettingham, Redgrave, and Burgate during the reign of Elizabeth I. These manors, located in Suffolk, the same county as the Bury Abbey, belonged to Bacon, and who had also received Redgrave, which had been absorbed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Indeed, Bacon had studied at Bury, received the lands after the dissolution, and continued to operate at these manors. It seems likely that this accounts for the survival of this manuscript. Under his custodianship, this manuscript was cut and repurposed as a cover for another book, which is the only reason it survived.

Further details

AUGUSTINE, DE CIVITATE DEI

Bury St Edmunds Abbey, England.

1140-1150.

390 x 259-278mm. Augustine, De civitate dei, Book 15, sections 18-20; Book 16, sections 4-6. Intact bifolium, 2 columns on each folio, with column B bisected on second folio; 43 lines, ruled in graphite. Book number in Roman numerals and partial “liber” along running head.

Typically suade-like feel of English parchment. Five sewing stations in gutter of bifolium. Possible quire signatures in gutter (2B, 2E). Round English minuscule with Bury features, particularly Scribe A. Matte black incaustum ink used. Frequent but legible abbreviations throughout.

Several contemporary scribal corrections using tie marks, or signes-de-renvoi, with corrected word or phrase in margin. 16th century pen-trials (“dwell in Earthe”) and marginal scribbles in ink. Inscription spanning both folios reads “Court book of Waltham, Mettingham, Redgrave, Burgate, Coll Manor, temp. R[egna] Eliz[abeth]”; “Chapter 20, starts here” and “12668” in modern pencil.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Thomson, Rod, “The Library of Bury St Edmunds,” Speculum , Oct., 1972, Vol. 47, No. 4

Webber, Teresa, “The Provision of Books for Bury St Edmunds Abbey in the 11th and 12th Centuries,”Bury St Edmunds Medieval Art, Architecture, Archeology and Economy, ed. Antonia Gransden, The British Archeological Association Conference & Transactions XX, 1998.

Sharpe, Richard, “Reconstructing the medieval library of Bury St Edmunds Abbey: the lost catalogue of Henry of Kirkstead,”Bury St Edmunds Medieval Art, Architecture, Archeology and Economy, ed. Antonia Gransden, The British Archeological Association Conference & Transactions XX, 1998.

Grandson, Antonia, “Some Manuscripts in Cambridge from Bury St Edmunds Abbey: Exhibition Catalogue,”Bury St Edmunds Medieval Art, Architecture, Archeology and Economy, ed. Antonia Gransden, The British Archeological Association Conference & Transactions XX, 1998.

Personal correspondence with Rod Thomson.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services