A Great Rarity and Defining Work on the Path to Our Modern Legal System: A Surviving Fragment Showing King Edward I’s and English Efforts in 1300 to Codify Law Just a Century After the Signing of the Magna Carta

Only 1 other copy known in private hands; Cited by, and a predecessor to, Blackstone, these fragments are from one of the earliest book of English law written in the language of the people and not Latin, at the behest of King Edward I of England

Only 2 copies exist in the United States and 1 in private hands; records of only 3 could be found having reached the public market; this copy, perhaps the earliest of them, last sold in the 1950s, when it was catalogued by great manuscript dealer Erik von Scherling as “unrecorded”

In a...

Only 2 copies exist in the United States and 1 in private hands; records of only 3 could be found having reached the public market; this copy, perhaps the earliest of them, last sold in the 1950s, when it was catalogued by great manuscript dealer Erik von Scherling as “unrecorded”

In a major step toward the writing of modern law books, this is perhaps the earliest work of European law – not merely English law – written in the language of the court and not the earlier custom of Latin

The sections pertain to inheritance law, one of the most important acts of perpetuity in any society, the leaving of one’s belongings to the next generation.

This document comes from the noted collection of Otto Fisher, prominent collector of the first half of the 20th century

The Norman Conquest was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of men from French provinces, including Normandy, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later called William the Conqueror.

The old English sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and was the foundation of further developments. They kept the framework of government but made changes in the personnel, although at first the new king attempted to keep some natives in office. By the end of William’s reign most of the officials of government and the royal household were Normans. The language of official documents also changed, from Old English to Latin.

Struggles between King and nobility led to the creation of influential and now famous legal texts that govern American law as well. This was in fact a remarkably important period of legal and societal transformation. As the pen of King John touched the parchment of the Magna Carta in 1215 on the fields of Runnymede, laws which remain a touchstone in England legislature and whose ripples impacted the United States’ Constitution and Bill of Rights were signed into effect. The Anglo-Norman period in England in particular saw the struggle for defining laws and the extent of governmental power.

In the late 13th century, history records that King Edward I set about on a project to codify the post-Conquest English laws in an effort similar to that embarked on by Emperor Justinian of the Roman Empire. This book would become a remarkable assemblage of contemporary law and serve as the first assemblage of English laws in French, which at the time was one of the languages of England. Its name as we call it today was the Britton.

Some scholars put the composition of the text between 1291-1292; others a couple decades earlier.

The Britton is considered the first text-book written in French; these fragments of juridical compilation bear witness to the development of the language and the law system of modern England and America.

In 1914, Hampton Carson, a scholar of the Britton and owner of an early manuscript, wrote in the Yale Law Journal, noting the great rarity of early manuscripts of this work. “Britton was the first great treatise written in the vernacular of the Courts of the period… This is of importance because it marks an epoch, just as Coke’s Institutes was the first important work upon our law composed in the English language…. It is the only treatise which on its face purports to have been promulgated by royal authority. The Prologue consists of a salutation by the King, ‘Edward, by the grace of God, King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine, to all his faithful people and subjects of England and Ireland, peace and grace of salvation…Desiring peace among the people who by God’s permission are under our protection, which peace cannot well be without law,.we have caused such laws as have been heretofore used in our realm to be reduced into writing according to that which is here ordained.'”

Britain’s linguistic history is a polyphonic one—before William the Conqueror brought his native dialect of French (Normand) to the island, the peoples spoke dialects of Germanic Anglo-Saxon (also known as Old English) as well as an array of Celtic languages, such as Welsh, Cornish, Manx, and Scottish. The Romance language of French mixed with the Germanic dialects, and from Old English, Middle English was born, and from the French of the Continent, the French of England, Anglo-Norman, was born.

The opening lines of Beowulf, arguably the most famous piece of Old English, demonstrates the gap between English from ca. 700-1000 and modern English, rendering the text nearly incomprehensible for us:

“Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum, þeod-cyninga þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.”

(“What! We of the Spear-Danes in days-of-yore of the people-kings glory heard, how the noblemen valor did.”)

Although the text from this French, Anglo-Norman document may seem foreign, an examination of the language reveals quite a few cognates, or words in common, with our own modern English:

“…chaumbres e issi des autres mesouns, solom ce q edit serra es pletz de dowere. Mes avowesons des eglise ne servage de soils, ne teles maneres des choses nient corporeles ne suffront point de partison en lur singulerete.”

(…”chambers, and so of other buildings, as shall be mentioned in the treating of please of dower. But advowsons of churches, servitudes of soil, and such kinds of incorporeal things are, from their nature, incapable of partition.”)

Words, such as chaumbres (chambers), dowere (dowery), avoweson (a legal term, advowson), servage (service), soil (soil, earth), maneres (manner, kinds), corporeles (corporal), suffront (to suffer, to endure), point (point), singulerete (singularity, a quality of being indivisible), immediately point to the manner of service the French language has given the development of modern English from Old English.

It is no surprise that when Edward went to create this important legal work, he did so in the language of the nobility, Anglo-Norman.

Two medieval manuscripts, circa 1300, on vellum, written in Normand, Anglo-Norman French, or the French of England during this time, containing important sections of one of the earliest English law books and the first ever in French, the original text prepared at the order of King Edward I. These historic documents also harken back to a trilingual England, wherein French, Latin, and English were the primary languages of the land. The sections pertain to inheritance law, one of the most important acts of perpetuity in any society, the leaving of ones belongings to the next generation.

Being sections of “On Mixed Actions” and “On Divisible Inheritance”. Select quotes:

“E solom lor sort de teles escrows se tiegne checun parcener a sa pupartie”

Translation: And according to the lot of those scrolls let each parcener [heir] take to his share.

“Mes laouweson de une eglise ne deit mye de partie tot seit acune foiz le cors del eglise deuisable ou de partable de antiquite par le reson de deiverses baronies.”

Translation: But the advowson [rights in] of a single church ought not to be divided, although sometimes by the body of the church may have become partible or divisible in ancient times by reason of different baronies.

Later provenance marks on the verso of fragment 1 include a ca. 18th c. hand quoting Cicero. Another, ca. 18th c. hand in darker, thicker black ink supplying what appears to be abbreviations. Modern pencil marks appear to be in the hand of Scherling.

Other details

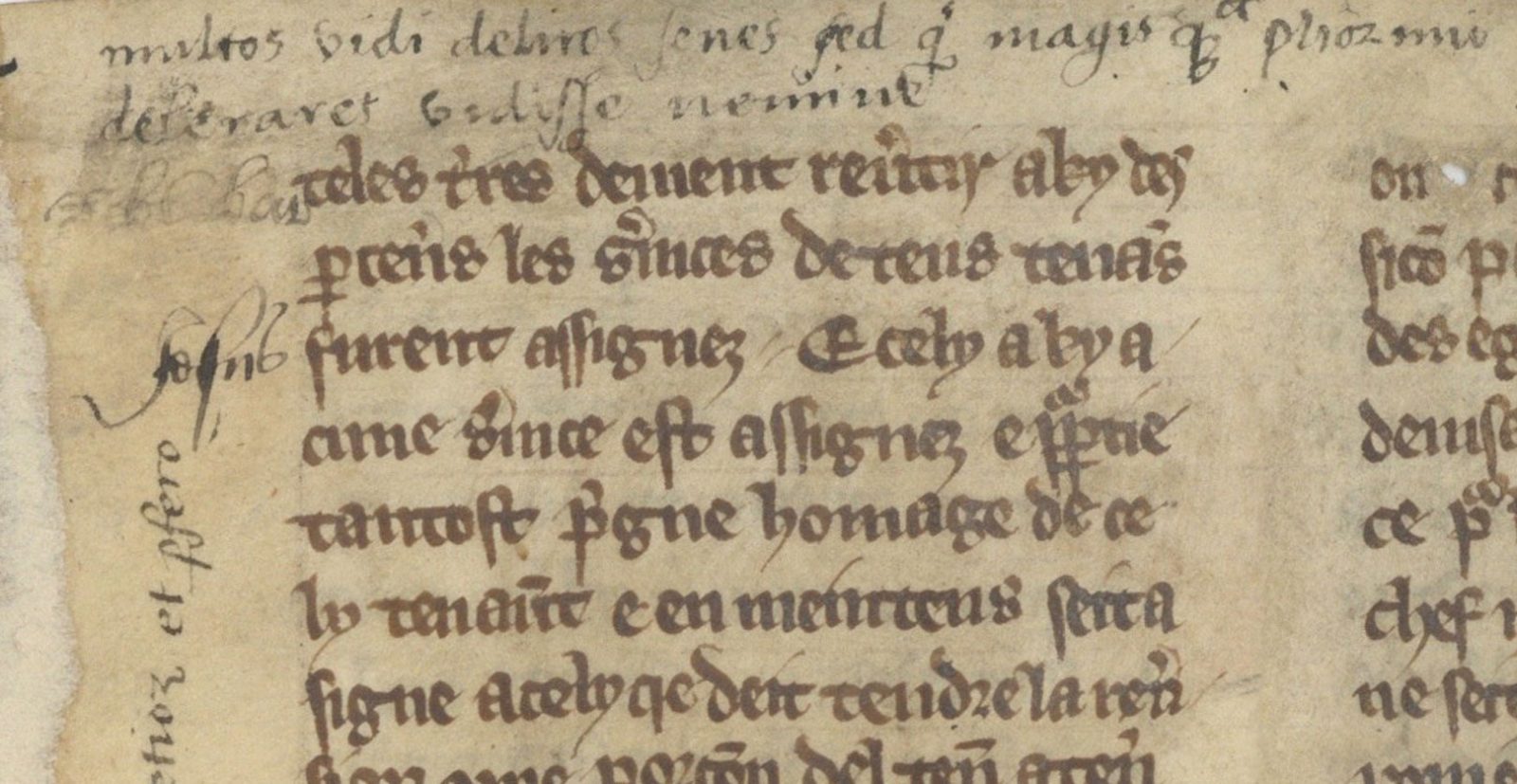

Two fragments from Book III, Chapter VIII, sections 8-10 of “De Accioun Mixte” and sections 5-8 of “De Heritage Devisable” from Britton. Each 164mm x 100mm. Originally double column; part of left-hand columns remain, with the bulk of right-hand columns; written with a dark brown ink, in a uniform size level of execution of a typically English Gothic Textura. Trimmed red pen flourish indicates presence of rubricated initial at the bottom of the recto of Fragment 1. Early modern and modern provenance marks.

England, c. 1300.

We found only 29 manuscript witnesses worldwide, of which 2 in the United States and 2, including this one, in private hands. Among them:

London, Lambeth Library 403 (late 13th or early 14th c.)

Cambridge, University Library, MS. Dd. Vii. 6 (hand resembles Lambeth; early 14th c.)

Cambridge, University Library, MS. Gg. V.12 (early 14th c.)

Cambridge, University Library, MS Hh. Iv 6 (14th c.)

Cambridge, University Library, MS Ff. ii. 39 (Late 14th c.)

Cambridge, University Library, MS Dd. Ix 38 (partial, middle 14th c.)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce 98 (early 14th c.)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS 562 (14th c.)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rawlinson MS C 898 (14th c.)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Balliol College Library MS No. 350 (partial, late 14th c.)

Landsdowne, MS 575 (early 14th c.)

Landsdowne, MS 574 (14th c.)

Oxford, Merton College Library, MS Q. 2.16 (early 14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS. 869 (early 14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 324 (early 14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 3644 (14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 5134 (14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 529 (14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 3937 (Late 14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 870

London, British Library, Harleian MS 489 (partial, early 14th c.)

London, British Library, Harleian MS 4656 (14th c.)

London, British Museum, Add. MS 25.458 (14th c.)

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 258 (early 14th c.)

London, Lincoln’s Inn Library, (partial, early 14th c.)

Fragment 1 text

Recto:

E solom lor sort de teles escrows…

… parceles de checune pupartie seint…

See p. 71-72, section 8-10, De Accioun Mixte, Liv. III, Chap. VII

Verso:

…teles terres deivent revertir a ky de parceners…

… puparties par sort ou par eleccion seit fet

See p. 72- 73, section 10-12, De Accioun Mixte, Liv. III, Chap. VII

Fragment 2 text

Recto:

…chaumbres et issi des autres mesons…

…iames nert le clerk resceva-…

See p. 76 -77, section 5, De Heritage Devisable, Liv. III., Chap. VIII.

Verso:

… partie e en division entre parceners…

… e fraunc mariage voloms qe ce….

See p. 77- 78, section 6- 8, De Heritage Devisable, Liv. III, Chap. VIII.

Fragment 1 Translation:

N.B.: This is the complete text for the sections represented in the fragments.

8. Afterwards let the parcels be entered and specified in several scrolls, and let those scrolls be delivered to some layman who knows nothing of letters or of the contents and let him deliver one scroll to each parcener; and according to the lot of those scrolls let each parcener take his share. And if any of the parceners has improved or damaged the land while it was in his hands, either in part or in the whole, let such damage be taken into account in the extent against the person who did it and likewise let his portion be increase according to the improvement he may have made. 9. If the sheriff be negligent in this matter, we will send our precept to the coroners of the district, or we will assign by our letters patent some Justice to execute it. For such delivery of shares touches very nearly upon the right of property by reason of the assignment of boundaries; and it is therefore necessary that such partitions be discreetly, properly, and lawfully made. 10. And whether such deliveries are made by lot or by election, the eldest parcener choosing first, and so one after the other according to their ages, let the parcels be presently imbreviated on a roll, that is to say, what each parcel is and how much, and between what bounds the parcel is assigned and to what parcener by name so that all the parcels of each share be enrolled , as well demesnes as fees and services and dowers or other lands held in any manner for term of life, which are to revert after the death of the tenants, and to whom] these lands are to revert, and to which of the parceners the services of such tenants are assigned. And he to whom any service is assigned towards his share shall forthwith take the homage of the tenant: and he who has to await the reversion shall have assigned to him in the meantime a portion of some other tenement according to the value of the land which is to revert to him, to be held until that land falls in. 11. If any one of the parceners die after the partition, not having any heir of his body begotten, then his share shall accrue to the other parceners or their issue, to be divided between them by equal portions, yet not by succession of inheritance for none of them is heir to the other, but by right of accruer. 12. And if any one of the parceners is not contented with the partition, we will cause the proceedings and the record to come before our Justices of the Bench and the plaintiff shall there state what errors have been made and the errors shall be there redressed by a new extent if need by. And after this assignment of the shares, either by lot or by election, let seisin be executed by judgement of our court.

Fragment 2 Translation:

[5. Sometimes the hall of a house is divided into two halves, or several parts and sometimes it is separated from the] chambers and so of other buildings, as shall be mentioned in treating of pleas of dower. But advowsons of churches, servitudes of soil, and such kinds of incorporeal things, are from their nature incapable of partition. Nevertheless several advowsons and several rights may admit of a partition among parceners, where each right remains entire. But the advowsons of a single church ought not to be divided, although sometimes the body of the church may have become partible or divisible in ancient times by reason of different baronies. For if a church is void by the death of the parson, and several parceners are patrons as one heir and one body, by reason of the unity of their right , no one has a right to the present to such church without the others until the advowson be wholly assigned to one of the parceners as a part of his share, or so limited by agreement between them, that one shall present one turn, the second the next turn, and so on in succession. And if any one before such agreement offers to present by reason of seniority, the clerk shall not be admissible [to institution, so long as any of the parceners oppose the presentation. 6. The likes of servitudes: for if a tenement to which a servitude is due falls] in partition and division among parceners, the servitude is neither diminished nor altered, but remains in its unity so far as regards to the land charged. And although a servitude is divided into several parts, as regards the land to which it is due by reason of the plurality of parceners, and although there may be several entire rights thereto, yet the land shall not be more burdened than it was before the partition, and thus the servitude shall remain in its unity. 7. There are some parts of an inheritance which will not admit of a division, and therefore ought to be wholly assigned to one of the parceners, satisfaction being made to the others according to the value out of the remainder of the inheritance. Such as vivaries, fisheries, hays, and parks, provided there are other hereditaments whereout satisfaction may be made in proportion to the other parceners. Nevertheless the parties may come to terms, and it is allowable, if they so agree, that one of them shall have one draught or one fish, or one beast in the park, and the second another, and a third the third, and so on. 8. With respect to land or other hereditament before given with any of the parceners in frank marriage, the usage shall be this; [that if she to whom the land was given in marriage chooses to share in the inheritance whereof their common ancestor died seised in demesne as of fee, she shall yield up and relinquish that which was before given her in marriage and so it shall fall into hotchpotch with the remainder of the inheritance, and then she shall take her share according to the chance of allotment with her other parceners…

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services