A Scientific Course Registration List from the Prestigious University of Berlin, Signed by Einstein (Teaching Relativity), His Supporters, His Detractors, and a Great Variety of Scientists from 1914-1926

An extraordinary and rare link between Einstein and the teaching of his theories; A unique and broad group of scientists and scholars

Not known to have survived, acquired from the direct descendants of the student and never before offered for sale

A glimpse into the great scientific community in pre-World War II Germany at one of its most distinguished institutions

Einstein signed in 1920, a year that saw him gain fame worldwide...

Not known to have survived, acquired from the direct descendants of the student and never before offered for sale

A glimpse into the great scientific community in pre-World War II Germany at one of its most distinguished institutions

Einstein signed in 1920, a year that saw him gain fame worldwide for his theory of relativity, and was pivotal in the attacks against him, and as he was working on the subject that would earn him his Nobel Prize 2 years later

Among the signers: The Father of Nuclear Chemistry, the Originator of the Idea of Continental Drift, 3 Nobel Prize Scientists, Influencers of Planck and Piccard, major names in Quantum Theory

Also signing are also those of Jewish origin who either died in the Holocaust or successfully fled in time

In 1905, a young patent clerk and physicist in Bern, Switzerland, Albert Einstein, obtained his doctorate and published a paper that exposed his newly developed Special Theory of Relativity. This unlocked many mysteries of the universe, and introduced the world to “E=mc2,” equating mass and the speed of light with energy. It established that time and space are not fixed, and in fact change to maintain a constant speed of light regardless of the relative motions of sources and observers. It showed space as a four dimensional universe, with time added as the fourth dimension. Just 10 years later, in 1915, Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity, in which gravitational effects are explained by the warping of space-time. In this theory, Einstein incorporated gravity as a geometric property of space-time. This expanded upon Special Relativity to describe the overall structure of the universe and the impulses of a gravitational universe. The two theories built on each other and were intimately related.

Success, however, did not mean fame, acceptance or respect. This took time and confirmation.

The success of Einstein’s 1905 landmark paper established him as an accomplished physicist. Upon request, he wrote several review articles explaining Special Relativity. He went on to devote his time to General Relativity. Many scientists did not accept Einstein’s ideas at first. But confirmation of his theory came in 1919 when astronomers documented the deflection of starlight by the Sun’s gravity. Einstein had predicted this phenomenon, but he could not foresee the fame that would follow.

Leading up to 1920, his fame rose and so did dissension within Germany. Although Einstein did win the Nobel Prize, it was not for relativity but for his work, starting in 1920 and culminating in 1921, on the photoelectric effect. But 1920 saw the height of the anti-Einstein and anti-relativity led by men like Paul Weyland and Ernst Gehrcke. Einstein being a Jew was sufficient to generate some of the opposition.

That year, German scientist Paul Weyland and Ernst Gehrcke (the two main speakers) organized a mass meeting at the Berliner Philharmonie to contest Einstein’s theory of relativity. After ensuring the meeting had been well-advertised in the newspapers, Weyland and then Gehrcke delivered vituperative attacks on Einstein. These attacks consisted primarily of unsubstantial insults against the theory of relativity alongside claims that it was promoted by “the clique of [Einstein’s] academic supporters”. Weyland claimed that the theory constituted a form of hypnotic mass suggestion and Jewish arrogance, which was a product of an unsettling spiritually chaotic period and that it, amongst other repellent ideas, was poisoning German thought.

Einstein was not awarded the Nobel Prize for his relativity work, in part because of the general domestic criticism against that work.

The early 20th century saw the establishment of Germany as the center of the scientific world. Many of the world’s leaders in this field studied and researched in Germany at a handful of places there. It was a golden age of science, one that was both beautiful and fairly short-lived, as many of these great men and women would lose their lives, jobs, safety or salaries once the Nazi control was complete. Even those not killed or chased from the country by the Holocaust were now working under grueling circumstances in a country torn by war and social upheaval. But in the late teens and 1920s, though they did not know it, the great scientists of the era were participating in a final flourishing of this German scientific era. One of the great universities of the era was the University of Berlin, where Einstein taught, along with Walther Nernst, Heinrich Rubens, and Otto Hahn, among many others. One of the men who was Einstein’s fellow teacher was Ernst Gehrcke, one of his chief critics.

One of the students at Berlin in this era was Paul Hess, who went on to become a science professor, inspired by these mentors.

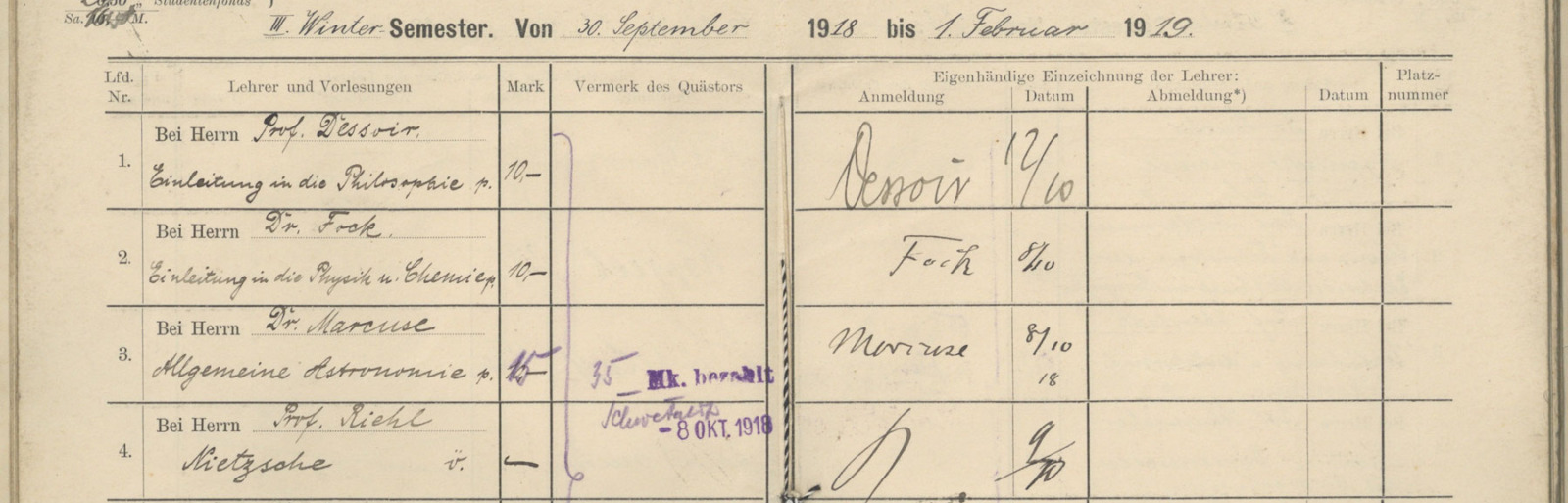

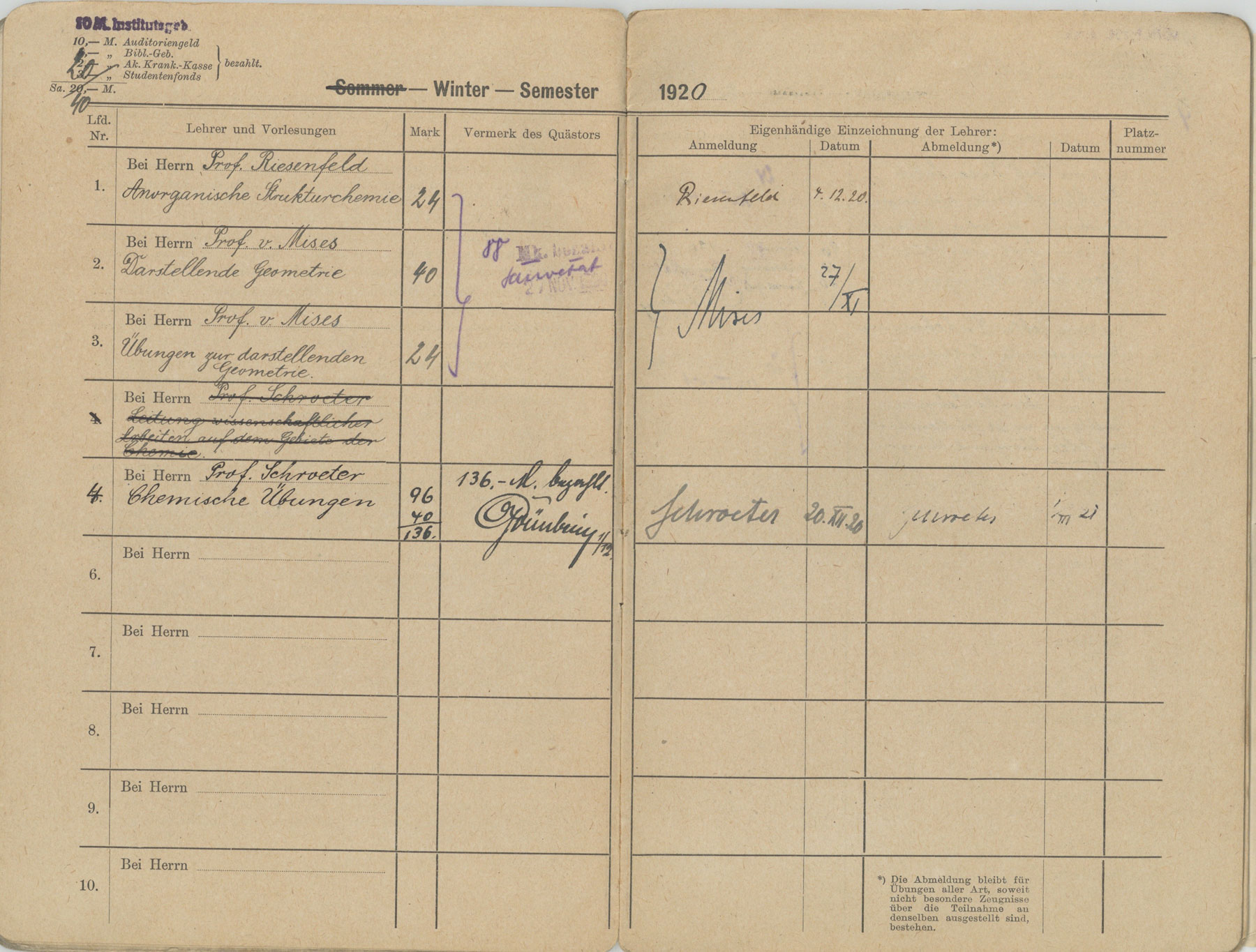

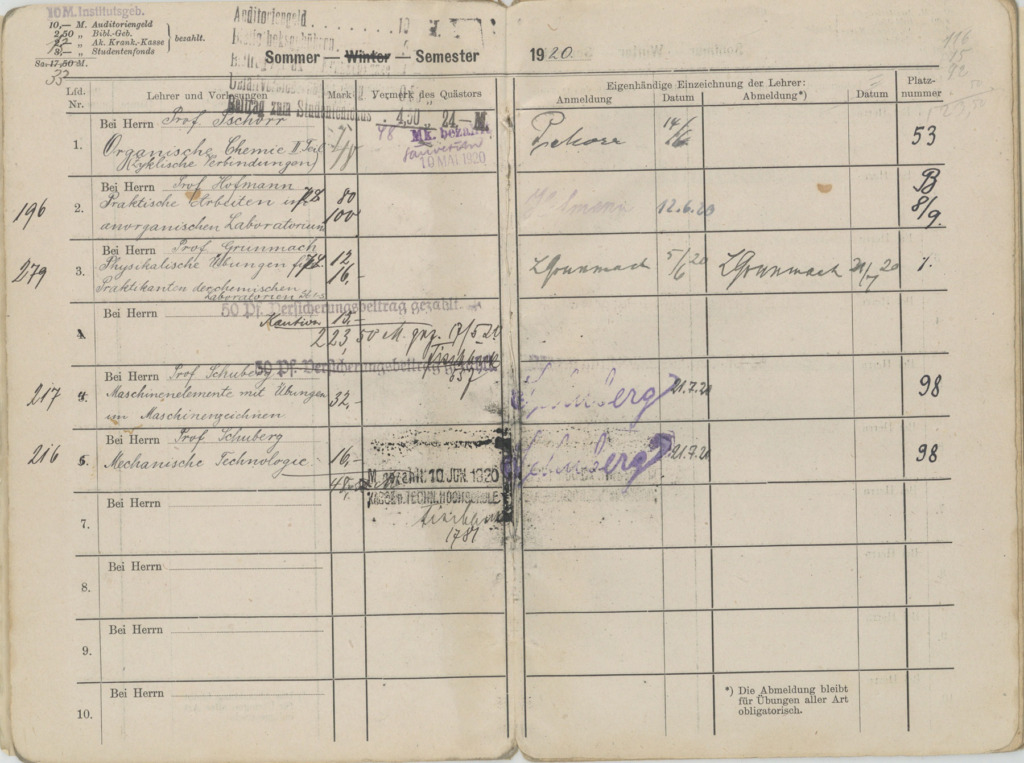

Document signed, Course registration booklet kept by scientist Paul Hess from 1914 through 1924. This contains certifications from the University Rector and Secretary attesting to his having completed the courses, along with graduation / leaving certification signed by the “Rektor,” Gustav Roethe. The book lists the names of the courses taken, the money paid, along with the attestation that the student had completed the work, which amounted to the signature of the Professor.

The are approximately 60 signatures contained in the book, among them:

Albert Einstein – the course Einstein taught to Hess was Relativity Theory. This was attested to by Einstein’s signature in February 1920, thus creating an extraordinary – and rare – link between Einstein and the teaching of his theories. That same year, on August 20, anti-relativity lectures of a distinctly anti-Semitic hue took place in Berlin’s Philharmonic Hall. It was a portent of things to come, that would in time bring Einstein to the United States.

Otto Hahn – chemist and winner of the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of nuclear fission. Hahn was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry and is widely regarded as the “father of nuclear chemistry.” Hahn’s most spectacular discovery came at the end of 1938 when, while working jointly with Fritz Strassmann, Hahn discovered the fission of uranium. This discovery earned Hahn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944, and led directly to the development of the atomic bomb. He taught Hess radioactivity.

Walther Nernst – a professor of physical chemistry at the University from 1905 and director of the Institute of Physics in 1925. He was Rector of the university in the 1921/22 academic year. Nernst was professor of experimental physics from 1924 until retiring with emeritus status in 1933. He was a co-founder of modern physical chemistry and did pioneering work in the field of electro- and thermochemistry. Among other things, he formulated the Nernst Distribution Law in 1890, invented the Nernst lamp (a precursor of the light bulb) in 1897, and discovered the Nernst Law of Electrical Nerve Stimulus Threshold in 1899. In 1906 he discovered the Nernst heat theorem, better known as the Third Law of Thermodynamics. Nernst was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1920 in recognition of his work in thermochemistry. Nernst also attended the August 20 event. He taught Hess inorganic experimental chemistry.

Alfred Lothar Wegener – a German climatologist, geologist, geophysicist, meteorologist, and polar researcher. He is known as the originator of the continental drift hypothesis by suggesting in 1912 that the continents are slowly drifting around the Earth. His hypothesis was not accepted by mainstream geology until the 1950s

Richard von Mises – professor of Applied Mathematics. In the face of rising antisemitism he left Germany in 1933 and spent the rest of his life in exile, first in Turkey, then in the United States. He is famous worldwide for his fundamental contributions in Applied Mathematics and in the development of Probability Theory and Statistics. The Richard-von-Mises-Lecture is held annually.

Ernst J. L. Gehrcke – he was a German experimental physicist and prominent critic of Einstein and relativity. Paul Weyland organized the major event in 1920 against Einstein mentioned above and gave the first presentation in which he accused Einstein of being a plagiarizer. Gehrcke gave the second and last talks, in which he presented detailed criticisms of Einstein’s theories. Einstein attended the event with Walther Nernst. Walther Nernst and Heinrich Rubens published a brief and dignified response to the event, in the leading Berlin daily Tägliche Rundschau, on August 26. Einstein published his own somewhat lengthy reply on August 27, which he later came to regret. Here he taught Introduction to Higher Mathematics to Hess.

Heinrich Rubens – physicist and the experimental professor of physics at Humboldt University. Rubens and his collaborator, Ferdinand Kurlbaum, had recently managed to measure the power emitted by a black body as a function of temperature at the unusually long wavelength of 51 microns. He was involved in the development of quantum theory. Rubens’ experiments led to Planck’s initial quantum hypothesis and Einstein’s Nobel Prize-winning interpretation of the photoelectric effect. Here he taught Experimental Physics to Hess.

Walter Hans Schottky – physicist who played a major early role in developing the theory of electron and ion emission phenomena, invented the screen-grid vacuum tube in 1915 while working at Siemens, co-invented

the ribbon microphone and ribbon loudspeaker along with Dr. Erwin Gerlach in 1924 and later made many significant contributions in the areas of semiconductor devices, technical physics and technology.

Hermann Schwarz – worked on the conformal mapping of polyhedral surfaces onto the spherical surface and on a problem of the calculus of variation, namely surfaces of least area. His most important work answered the question of whether a given minimal surface really yields a minimal area. An idea from this work led Émile Picard to his existence proof for solutions of differential equations. It also contains the inequality for integrals now known as the ‘Schwarz inequality.’

Dr. Fock – In computational physics and chemistry, the Hartree–Fock (HF) method is a method of approximation for the determination of the wave function and the energy of a quantum many-body system in a stationary state.

Max Bernhard Weinstein – physicist and philosopher. He is best known as an opponent of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and for having written a broad examination of various theological theories, including extensive discussion of pantheism. He was Jewish. He taught pantheism to Hess.

Johannes Wolf – German musicologist, archivist and teacher, known for his research on medieval and Renaissance music, particularly Ars Nova, and early music notation.

Rudolph Eberstadt – an important city and urban planner whose work is still used today. He taught Hess National Economics.

Friedrich Hermann Leuchs – German chemist. Leuchs’s research dealt with the chemistry of amino acids and the chemistry of strychnine. The Leuchs reaction and the Leuchs anhydride were named after him. He taught Hess organic chemistry.

Ernst Hermann Riesenfeld – German/Swedish chemist. Riesenfeld started his academic career with important contributions in electrochemistry by the side of his mentor Walther Nernst, and continued as a professor with work on the improvement of analytical techniques and the purification of ozone. Dismissed and prosecuted in Nazi Germany due to his Jewish origins, he emigrated to Sweden in 1934 and continued his ozone-related work there until retirement. Further hitherto unmeasured physical properties of pure concentrated ozone were determined by the Riesenfeld group in the 1920s.

Wilhelm Traube – German chemist. Died as a Jew during the Holocaust. He taught Hess Qualitative chemical analysis

Karl Hermann Wichelhaus – founder of the original technology institute at Berlin.

Herbert Marcuse – German–American philosopher, social critic, and political theorist.

The importance and rarity of this course book cannot be understated. It connects Einstein directly with the teaching of relativity, sees him in an academic setting as a professor, provides a snapshot of German science at the time, and is accompanied by scores of other significant signatures. We have never had anything like it, nor seen anything like it come across our desk in our 35 years in this field. Obtained by us directly from the Hess heirs.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services