Sold – The Last Will and Testament of John Brown

The last act in the life of the man whose execution brought on the Civil War.

In the 1830’s, Brown became involved in efforts to secure freedom and justice for African-Americans. He was inspired by Nat Turner – the Virginia slave who led a bloody armed rebellion against plantation owners that left 55 white southerners dead, and by Cinque – the leader of a successful revolt on...

In the 1830’s, Brown became involved in efforts to secure freedom and justice for African-Americans. He was inspired by Nat Turner – the Virginia slave who led a bloody armed rebellion against plantation owners that left 55 white southerners dead, and by Cinque – the leader of a successful revolt on the Spanish slave schooner Amistad. Brown became a stationmaster in the Underground Railroad, constructing a hiding place in his barn and taking fugitive slaves on nocturnal rides north to the next station. Then, in November 1837, came a turning point in Brown’s life – a proslavery mob destroyed the presses of an antislavery newspaper near St. Louis and murdered its editor, Elijah P. Lovejoy. At an antislavery meeting in Ohio called to protest the murder, Brown suddenly stood up, raised his right hand, and announced, “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!”?

Brown first revealed his plan to incite a slave insurrection in the South to Frederick Douglass when the famous black abolitionist visited his Springfield, Massachusetts home in November 1847. Pointing to the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia on a large map on his table, Brown told Douglass that God placed them there “to aid in the emancipation of your race” and they were “full of good hiding places, where a large number of men could be concealed and baffle and elude pursuit for a long time.” He confided that he hoped to invade with “twenty-five picked men” who would sneak on to plantations, liberate slaves, and then retreat with them to the protection of the mountains, eventually forming a black colony there. These invasions, he said, would also have the effect of energizing additional abolitionist activity in the North.

A few years later, after Brown moved to a farm in North Elba, New York to live in the largely black community established at that scenic location, he began to focus his thoughts on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. By 1854, Brown was actively recruiting men to participate in his planned attack on Harper’s Ferry. It would be five more years, however, before he could put his plan into action. In the meantime, he became drawn into the drama that was unfolding in the Kansas Territory. In 1854, the infamous Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the western territories to slavery. The next year, Brown followed three of his sons to Kansas, hoping to do whatever he could to prevent the state from falling into the slavery column. Henry Thompson, his son-in-law and loyalist, accompanied him. Both sides dug in for a titanic struggle on the slavery question. Southerners, including many slave owners in neighboring Missouri, believed that if Kansas went for slavery, other western territories – in a sort of domino effect – would do likewise. They pledged to drive antislavery settlers out of Kansas. Northerners saw the battle as equally important, and antislavery activists headed west and began establishing camps in the territory.

In 1856, President Franklin Pierce announced his support for the corrupt proslavery legislature in Kansas and proclaimed opposition to it treasonable. In May, Brown’s outspoken attacks on the proslavery legislature led a judge to issue warrants for the arrest of him and his sons. On May 21, over 700 border ruffians and proslavery men, waving banners proclaiming the supremacy of the white race, swept down on the antislavery town of Lawrence, ransacking two antislavery presses and burning and looting homes and businesses. Following news of the raid on Lawrence, a friend described Brown as “wild and frenzied.” The next day, May 22, South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks took his gold-topped cane and, on the floor of the U. S. Senate, clubbed senseless Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner after he delivered an abolitionist speech, “The Crime Against Kansas.” When Brown received word of the caning in Washington, according to his son Jason, “it seemed to be the finishing, decisive touch.” Brown told his supporters, “I am entirely tired of hearing that word ‘caution.’ It is nothing but the word of cowardice.”

Brown was determined to make slave-owners pay a price for all this, and he and six others set out from Ottawa Creek on May 23 with rifles, revolvers and swords, heading toward Pottawatomie in proslavery territory. Around ten o’clock the following night Brown’s men, announcing they were from the Northern Army, broke into the home of proslavery activist James Doyle. Doyle and his two older sons were led into the woods near the cabin and hacked to death. The group then headed to the cabin of Allen Wilkinson, a proslavery district attorney. Wilkinson met the same end as the Doyles. A short time later, the fifth and final victim, William Sherman, was taken and killed. Afterward, Brown remained unapologetic, saying “God is my judge.” Pottawatomie changed the way Southerners viewed northern abolitionists. No longer did they see them all as toothless pushovers – they began to see them as radical and potentially dangerous.

Over the next two years, Brown – now a nationally known figure – divided his time between the efforts to secure free state status for Kansas and planning for his invasion at Harper’s Ferry. One exploit increased his fame. On the night of December 20, 1858, Brown engaged in a memorable raid that panicked slave-owners and transformed him, in the minds of many influential northerners, into the practical man of action needed to bring a swift end to the evil institution of slavery. He rode with twenty of his men into Verona County, Missouri, where they forcibly liberated twelve slaves from two farms and begin leading them on a successful 82-day, one thousand mile winter journey to freedom in Canada. The slave liberation prompted Gerrit Smith, the noted financier of the abolition movement, to say, “I was once doubtful in my own mind as to Captain Brown’s course. I now approve of it heartily.”

After that, Brown focused on final preparations for the Harper’s Ferry assault, raising additional men and money, and securing necessary weapons. He was getting anxious to move. “Talk! talk! talk!” he complained at a meeting in Boston. “That will never free the slaves. What is needed is action.” He finally put his grand plan into play on July 3, 1859, when he and three other men scouted the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, a town nestled on a peninsula amid the high banks that surround the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. The town manufactured more weapons than any other place in the South, and almost 200,000 weapons were stored in the United States Armory located there. Brown’s plan was to take the arsenal, arm freed slaves in the vicinity, and then retreat to the mountains where they could mount additional raids to free more slaves. The next day, he headed across the Potomac to Maryland, and rented an off-the-beaten-track place to house and train his soldiers for the raid. Over the next two months, additional recruits arrived and the men prepared rifles, studied military strategies, and relaxed in song or games of checkers and cards.

On October 16, 1859, Brown led 21 men on the long-planned raid. The early stages of the plan went well. Wires were cut and bridges taken without bloodshed. Brown, announcing his intention “to free all the negroes in this state,” seized the night watchman at the federal armory, took the arsenal and captured hostages. Brown began waiting for news of his raid to reach local slaves, whom he expected would then rebel against their white masters. Six men were sent to the countryside by Brown to get the liberation process going and to give each freed slave a pike, either for defensive purposes or to guard white slave owners so as to prevent their escape. Unfortunately for Brown, the slaves did not respond as he had hoped and were too confused and frightened to come to his aid. By the next day, citizen soldiers and two militia companies from nearby Charlestown arrived and retook the bridges and soon surrounded the federal arsenal. At that point, Brown and his company were holed up in the armory with no way to escape. As the situation continued to deteriorate, Brown and his men moved with eleven of their key hostages to the fire-engine house, a brick building that became know as John Brown’s Fort, the site of his last stand. A fierce gun battle ensued in which Brown’s son and others were killed. At 11 p.m., a company of U.S. marines commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived at Harper’s Ferry. At dawn on October 18, a lieutenant chosen by Lee approached the engine-house and delivered to Brown Lee’s formal demand for surrender. When Brown rejected the offer, marines stormed the engine-house, battering it with sledgehammers. In the fight that ensued, Brown was stabbed, but not fatally. Many of his men, however, died by either gunfire or bayonets, and Brown and four of his surviving men were taken prisoner. Brown was carried to the armory, where a group of reporters and politicians, including Virginia’s Governor Henry Wise and two U. S. senators, questioned him. He told his interviewers that he came to Virginia at the prompting of “my Maker” and his only objective was “to free the slaves.” Asked how he felt about the failure of freed slaves to enthusiastically embrace his liberation, Brown said, “Yes. I have been disappointed.” After the interview, Governor Wise, while abhorring Brown’s views, pronounced him “the gamest man I ever saw.” Brown’s exploit electrified the nation, and his subsequent trial led to his becoming, for many northerners, a saintly martyr who showed that eradication of slavery throughout the land was the only answer to the divisions in America. Brown and his fellow prisoners were transported eight miles to Charlestown, where they were arraigned on three state charges: treason against Virginia, inciting slaves to rebellion, and murder. Andrew Hunter was named the prosecutor, and later wrote, “…not only the prosecution of the prisoners was committed to me, but also everything connected with the state of affairs or with the raid. I had not only to take charge of the trials, draw the indictments, etc., but to see that the prisoners were well secured and cared for and made comfortable. My instructions from Governor Wise were to see that every comfort and privilege consistent with their condition as prisoners should be afforded them. This was religiously done…Over and over again, in accordance with my instructions from Wise, I told Brown that anything he wanted, consistent with his condition as prisoner, he should have. On October 26 the trial began in a supercharged atmosphere. There was considerable speculation that Brown would plead insanity. Brown, however, would have no part of it. He called the insanity plea a “pretext” and rejected “any attempt to interfere in my behalf on that score.” Witnesses told jurors that Brown had treated hostages respectfully, but the facts were not in dispute and Brown refused to deny that he had acted with intention to free the slaves and that the raid that resulted had led to deaths. He was convicted.

On November 2, Brown appeared in court for sentencing. After overruling defense objections to the verdict, the Judge asked Brown if he had anything he wished to say before being sentenced. Brown immediately rose and in a clear, distinct voice delivered one of the most memorable courtroom speeches ever by a defendant in a criminal case. Ralph Waldo Emerson would later call it, along with the Gettysburg Address, one of the two greatest American speeches. Brown said: “Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved…had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so called great, or in the behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right. Every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment. This court acknowledges, too, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed, which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament, which teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to remember them that are in bonds as bound with them. I endeavored to act up to the instruction. I say I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely admitted I have done, in behalf of his despised poor, I did not wrong but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I say let it be done.” Judge Parker listened silently to Brown’s speech. Then he sentenced him to be publicly hanged on December 2. When the Judge pronounced his sentence, just one man in the crowd clapped, the rest were struck silent. Brown was returned to his cell in the Charlestown jailhouse to wait out his thirty remaining days, and was allowed by his jailor to write his wife, telling her that “I am to be hanged on the second of December.” While waiting for his execution, he conducted himself nobly with both tongue and pen. Meanwhile, in many areas of the North concern for Brown was blossoming into adulation. He was perceived as a new and more venerable figure who was brave and God-like and bore no malice toward his captors. Millions of people had read or heard of his heroic behavior at the trial.?

On December 1, the day before the execution, Brown’s wife arrived at Harpers Ferry from Philadelphia, and there in the jailhouse, as the North looked on, John and Mary Brown spoke to one another for the last time. For a few hours they talked about God and the education of their children.? He wrote out and signed a will making numerous bequests to family members, and gave that will to his wife.? Then, under the protection of a military escort provided by General Taliaferro of the state militia, Mary Brown returned to Harpers Ferry to await the delivery of her husband’s body. Early the next morning Brown prepared a codicil to that will and sent it to her along with a cover letter saying farewell. He then also wrote his famous prophesy of Civil War – “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had as I now think vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.” The Brown family took this December 1 will home to New York and used it to dispose of Brown’s estate. Brown’s son-in-law, Henry Thompson, wrote out a copy of this document as it was being probated on December 18, 1859, and this copy was retained by the Brown family. Brown’s son Salmon later sold the original December 1 will to a collector, and it is now in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.?

However, Brown’s mind was troubled about property he thought might not be sufficiently covered in the December 1 will, and on December 2, as apparently his final act, he dictated a later will, revoking all previous ones. Prosecuting attorney Andrew Hunter relates the story of Brown’s last moments in prison, and of this last will. “From the time he was captured until his execution, I was with him almost daily, as we soon got on good terms and he frequently sent for me…On the morning of the 2nd of December a messenger from Brown came to my office in Charlestown, saying that Captain Brown wanted to see me at the jail. Though extremely busy making arrangements for the execution that day, I dropped everything and went at once to the jail. There to my surprise I learned from Brown that he wanted me to draw his will. He had been previously advised by me that as to any real estate he had the disposition of, it would be governed by the laws of the state where it was situated, as to which I could not advise him, but as to any personal property he possessed he could dispose of it here in Virginia. He accordingly asked me to draw his will. I said to him, ‘Captain, you wield a ready pen, take it, and I will dictate you such a testament as to this personal property in Virginia as will hold good. It will be what is called a holographic will; being written and signed by yourself, it will need no witnesses.’ He replied, ‘Yes, but I am so busy now answering my correspondence of yesterday, and this being the day of my execution, I haven’t time, and will be obliged if you will write it.’ Thereupon I sat down with pen and ink to draw the will, and did draw it according to his dictation. After the body of the will had been drawn he made suggestions which led to drawing the codicil. It was drawn as he suggested it, and both the will and the codicil are attested by John Avis and myself, and were probated in Jefferson County [Virginia]. This all occurred a short time before the officers came to take Brown out to execution. As evidence of his coolness and firmness, while I was drawing the will he was answering letters with a cool and steady hand. I saw no signs of tremor or giving way in him at all. He wrote his letters, each one of which was handed to me before it went out, while I was drawing the will, so as to get done by the time the officers came to take him out. When they finally came to take him, he grasped me by the hand and thanked me in the warmest terms for the kindness I had shown to him from the beginning down to that time.”? Two manuscripts

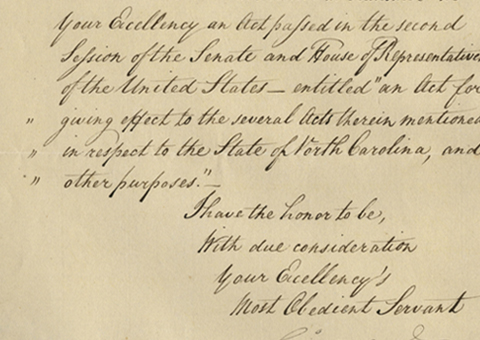

Shown on page 31:? Document Signed, the Last Will and Testament of John Brown, Charlestown, December 2, 1859, being the very document Hunter discusses above. It reads, “I, John Brown, a prisoner, now in the prison of Charlestown, Jefferson County, Virginia, do hereby make and ordain this as my last will and testament. I will and direct that all my property, being personal property, which is scattered about in the States of Virginia and Maryland, should be carefully gathered up by my executor, hereinafter appointed, and disposed of to the best advantage, and the proceeds thereof paid over to my beloved wife, Mary A. Brown. Many of these articles are not of a warlike character and I trust as to such, and all other property that I may be entitled to, that my rights and the rights of my family may be respected; and lastly I hereby appoint Sheriff James W. Campbell executor of this my last true will, hereby revoking all others.” Following Brown’s signature are those of witnesses – his prosecutor, Andrew Hunter, and his jailor, John Avis. This first page is quite faded from exposure to sunlight while displayed a century ago, though it is completely legible. On the verso is a signed codicil. “I wish my friends, James W. Campbell, Sheriff, and John Avis, Jailer, as a return for their kindness, to have a Sharp rifle, of those belonging to me, or if no rifle can be had, then each a pistol.” The writing on this side is darker and easily read.?

This page:? Included with this is the very copy that Henry Thompson copied from the December 1 will.? This document is entirely in the hand of Thompson and signed by him. ?

This December 2 will was filed and probated in Jefferson County, Virginia shortly after Brown’s execution. After the Civil War ended, that county became part of the new state of West Virginia, and the county seat was moved to Shepherdstown. The new county offices did not have room for all the records and the old, inactive ones were simply discarded. These included, incredibly, John Brown’s will. Fortunately, someone understood the will’s historic significance and salvaged it. Judge Joseph A. Chapline, in the words of his wife in a letter dated April 25, 1877 which is included, “rescued this will from the waste paper and had it framed.” It resided in a few notable collections during the 20th century until coming into our hands more recently.

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry drove a wedge between North and South, and did much to bring on the Civil War just over a year later. Northerners began to focus on and sympathize with his goals and, for many, his actions. “He did not recognize unjust human laws, but resisted them as he was bid…,” said Henry David Thoreau in an address to the citizens of Concord, Massachusetts. In the South, the idea of slave rebellion now seemed real and caused wide-spread fear, leading to the conclusion that southerners needed to defend themselves and their institutions. Militias formed and secession ceased to be a crank idea and was on more and more tongues. And the war came.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services