Henry Clay Writes Pres. Taylor Hoping He “may be able to preserve to our country the blessings of peace.”

As the Controversy Over Slavery Explodes in 1849.

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

The annexation of Texas in 1845 caused the controversy over slavery to heat up, but the Mexican War intervened to deflect attention. When the war ended in early 1848, vast lands in the West were acquired from Mexico, and the question of whether slavery would be allowed in these territories quickly reignited...

The annexation of Texas in 1845 caused the controversy over slavery to heat up, but the Mexican War intervened to deflect attention. When the war ended in early 1848, vast lands in the West were acquired from Mexico, and the question of whether slavery would be allowed in these territories quickly reignited the flames of sectionalism. In 1849, the discovery of gold led to a land rush in California, and the territory filled quickly with people. With partisans on both sides angrily stirring the pot and fears rising that the country might be split asunder, it was apparent that the matter of slavery had become urgent.

Europe appears to be in a state of great and general disorder. A war embracing the larger part of it seems to be almost inevitable. England and France can hardly look upon the Russian interference in the affairs of Austria and Hungary with indifference. I sincerely hope that you may be able to preserve to our country the blessings of peace.

The United States was not then the sole nation in turmoil. In 1848, a series of political upheavals spread throughout the European continent. Described by some historians as a wave of revolutions, the period of unrest began in France but then propelled itself onward. It lasted well into 1849, ending in August with the defeat of Hungarian insurgents.

Henry Clay was three times the Whig candidate for president, and three times he was defeated, the final one being in 1844. He expected to run again in 1848, but many Whigs feared he could not win. Instead, Zachary Taylor, a Mexican War hero, won the Whig nomination, depriving Clay of the prize. As a candidate, Taylor had sidestepped the entire slavery controversy, but now that he was President he began developing what was seen as a pro-Northern solution. One of the leaders in Congress with whom he would have to deal on this and other subjects was Clay, who straddled the fence between the North and South and would not agree with his approach. Thus, Taylor and Clay were two men who saw themselves as political opponents, and many wondered what the relationship would be between the party’s long-time spokesman and its new sitting President, and whether they could work together. This would have national as well as party consequences, considering the issues facing the country. Their relationship was made all the more complicated by men seeking advantage from Tayor by trying to drive wedges between and Clay.

Shortly after Taylor was inaugurated President in March 1849, Clay began getting reports that Taylor had ill will towards him and was speaking against him personally. On April 30, 1849, he received a letter from a friend Thomas Stevenson, saying that the reports were true but that he felt that experienced Washington hands would restrain Taylor from any overt actions against Clay. He stated that one Buckner H. Payne had related that this latter supposition was so, that Taylor was now speaking well of Clay. Stevenson added that peace between the two leaders was necessary for the country.

On May 12, to test the waters Clay wrote Taylor directly, asking if he might appoint Clay’s son James to a diplomatic post. On May 28, the President responded by saying he was displeased with Payne having reported his conversation, but that he had only positive feelings about Clay, and that “it would afford me great pleasure to comply with your wishes” and appoint James Brown Clay as U.S. Ambassador to Portugal. The following is Clay’s response to Tayor, in which he makes short work of Payne, thanks the President for his friendly manner and for appointing his son, references that “strenuous exertions” were being made to alienate the two leaders, mentions the crises in Europe, and thinking of conflict there, ends by expressing his hope that Taylor can preserve peace in the United States.

Autograph Letter signed, Ashland, June 6, 1849, to President Taylor. “I received your obliging letter of the 28th Ult., and on behalf of my son as well as myself I beg leave to tender an expression of our grateful thanks and great obligations for the prompt and friendly manner in which you have been pleased to accede to our wishes that he might be employed in the public service on a foreign mission. The time indicated by you for his departure on suits him very well as he could not have conveniently left home in a shorter period. He will immediately commence his arrangements for going abroad and will be prepared in due season to obey the orders of Government.

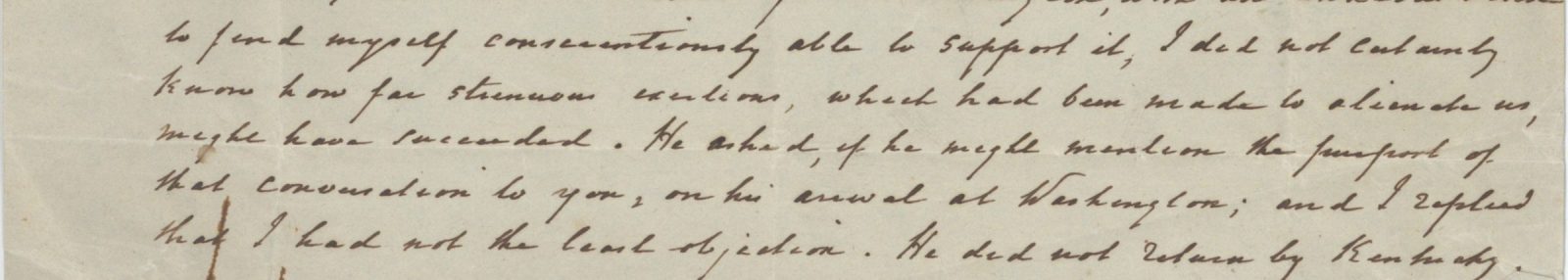

“I had known Col. Payne (referred to in our last letter) in Kentucky, and had some business in which he conducted himself with integrity; but not living in the same neighborhood, I rarely saw him, and there was no very good intimacy between us. Last winter, when he approached me in New Orleans, I understood him to be a particular friend of yours. Standing in amiable relations as I supposed, to us both, and being about to go to Washington, I conversed freely with him on public affairs. He wanted me to recommend him for the office of Collector of that city, which I declined to do for several reasons; among others, that I had adopted as a general rule not to interfere in mere local appointments in other and distant states from that of my residence. I must confess that I was surprised that Mr. Payne should be an applicant for that office, and still more at the confidence with which he purposed to anticipate success. In the course of the conversation between us I probably remarked to him that I did not know that a recommendation from me, if I could give him one, would benefit him; for that, whilst my own feelings towards the President and his administration were entirely amicable, and that I should go to Washington with an anxious desire to find himself conscientiously able to support it, I did not know how far strenuous exertions, which had been made to alienate us might have succeeded. He asked if he might mention the purport of that conversion to you on his arrival at Washington; and I replied that I had not the least objection. He did not return to Kentucky, as you supposed, but on his reaching New Orleans he wrote to me, communicating an account of his visit to Washington, and of the friendly purport of his conversation with you about me. I ought to add that Mr. Payne is a member of an extensive and generally respectable connection in this state; but that one of his near relations has recently spoken of him to me in rather unfavorable terms. Personally I know nothing to his disadvantage.

“Europe appears to be in a state of great and general disorder. A war embracing the larger part of it seems to be almost inevitable. England and France can hardly look upon the Russian interference in the affairs of Austria and Hungary with indifference. I sincerely hope that you may be able to preserve to our country the blessings of peace.” He signs the letter “with the highest respect, faithfully your friend…” The letter is not in the “Henry Clay Papers” and appears to be unknown and unpublished.

Clay’s son James went to Lisbon. Later he served in the House of Representatives from 1857-59. The tattler Payne did not receive the appointment as Collector he craved, and for which he inappropriately manipulated conversations of both Clay and Taylor. After the Civil War, he ignominiously wrote a book claiming that Negroes were not the same species as whites.

President Taylor soon developed a policy favoring the immediate admission of California and New Mexico as free states, avoiding the entire territorial process. Many in the South were unwilling to consider this, and Clay opposed the statehood solution in isolation, preferring instead to fashion some kind of game-changing compromise. In January 1850, Clay introduced the Compromise of 1850. Taylor opposed it, but it would pass after his death when Clay supporter Millard Fillmore ascended to the presidency.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services