Original, Unpublished Notes for Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia, Prepared for the Invasion, from the Archives of Napoleon’s Senior Aide de Camp Charged with Planning that Invasion

Sent at Napoleon's direction to General Georges Mouton, the remarkable, 14-page manuscript gives directions to a prospective invading army, listing populations, topography, opportunities for provisioning, bridges to cross, etc.

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

It is based on an 1809 intelligence operation that Napoleon commissioned to chart Persia, Russia and the steppes

A remarkable and apparently unpublished manuscript documenting Russia and its environs in the early 1800s, fascinating for that purpose as well

Acquired from the direct descendants and never before offered for sale

...It is based on an 1809 intelligence operation that Napoleon commissioned to chart Persia, Russia and the steppes

A remarkable and apparently unpublished manuscript documenting Russia and its environs in the early 1800s, fascinating for that purpose as well

Acquired from the direct descendants and never before offered for sale

“Resistance could only result in the burning by the assailant of a large part of the wooden houses of Moscow”

“Minsk is a town of 10,000 inhabitants of which two thirds are Jewish.”

In 1803, Camille Alphonse Trezel obtained the rank of lieutenant in the corps of topographical engineers. The next year he was promoted to assistant engineer geographer. After the Polish campaign, as a lieutenant, he was appointed acting aide to General Gardanne, in the embassy of France to Persia. He was commissioned at this time by Napoleon to take extensive notes, topographical, geographical and otherwise of Persia and its environs. On his return, he came through Russia. On his return to France, he was promoted to Captain in late 1810 / early 1811 and assigned as an aide-de-camp to General Armand Charles Guilleminot; he became lieutenant-commander in 1813. Napoleon aimed to defeat not only Russia but England, and the latter in part through India. Trezel and Gardanne in 1809 were tasked to survey the vast regions that would have to be crossed and to probe the dispositions of the populations, and as evidenced here, did so.

Trezel’s notes on Persia are published and important primary resources for the period and region. We found no record of the publication of his notes on Russia.

In May and June 1812, Napoleon turned to mapping the pending invasion of Russia and finding the correct route. He had few great options. As the published papers of Napoleon state, “Despite the efforts of his geographical engineers, Napoleon never had good maps of Russia throughout the campaign. To compensate for this shortage, the Paris topographical office should have drawn large numbers of the few available maps and given them to the corps commanders. This was not done on the scale that the emperor wanted.” He complained during this stretch that he needed more routes to Russia, that one would not suffice for planning, and he wrote to Generals Clarke and Berthier complaining on this subject.

On June 24, 1812 Napoleon commenced his famed campaign in Russia, ordering his Grande Armée, the largest European military force ever assembled to that date, into Russia. The enormous army featured more than 500,000 soldiers and staff and included contingents from Prussia, Austria, and other countries under the sway of the French empire. The campaign would be characterized by the massive toll on human life: in less than six months Napoleon lost near half of his men because of the extreme weather conditions, battle, disease and hunger. On both sides, nearly a million soldiers and civilians died.

General Mouton, the Count of Lobau, was a prominent general and later Marshall of the Empire for Napoleon. Mouton means “lamb” in French, the source of Napoleon’s now famous statement on Mouton: “My lamb is a lion.” Napoleon valued Mouton to the extent that for his great Russia campaign he made him senior aide to camp. In 1806 Mouton was a Brigade General. He would remain in Napoleon’s service until the end of the Empire, during which time he showed himself to be forthright, direct (“he’s no fawner”, Napoleon is noted to have said) but also disciplined, loyal, meticulous and highly organized. He was at Austerlitz with Napoleon and was charged with the preparation of the campaigns in Spain (1808), Russia (1812), Germany (1813), and Belgium (1815). Napoleon also wrote “Mouton is the best colonel to have ever commanded a French regiment.” In 1812 Mouton took an active part in the planning and enacting of the Russian campaign. When Napoleon left the army during the retreat and returned to Paris, Mouton accompanied him.

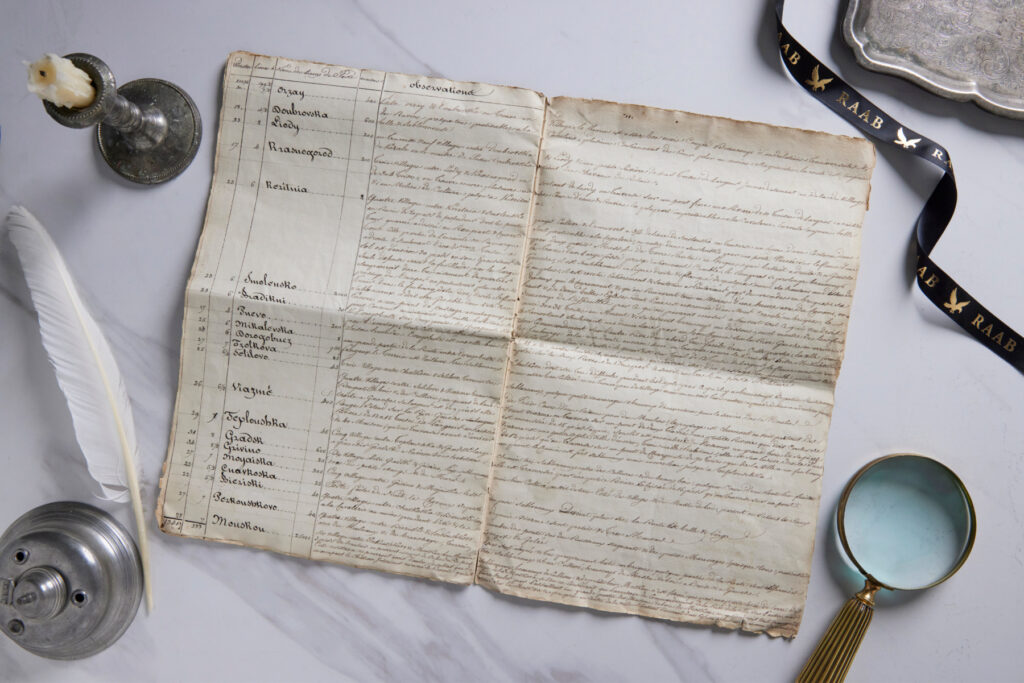

Manuscript, in the hand of an intelligence officer, likely from the topographical department, from the Library of Georges Mouton, no date but likely late Spring 1812. The manuscript notes the position of Trezel as Captain and aide to camp for Guilleminot, a position Trezel effectively occupied between 1811 and 1812. It appears to be a shortened version of the report from the 1809 intelligence operation that Napoleon commissioned. Our gratitude to the Fondation Napoleon for their generous assistance.

“Notes on the Route from Warsaw to Moscow by Tykoezinn frontier of the Grand Duchy [of Warsaw] (47 leagues), Grodno (77 leagues), Mir (133), Mink (158), Orzay (208), Smolensk (237) and Moscow (333). Extracts from a voyage made in July 1809 by Captain Trezel, aid de camp of General Guilleminot.”

The following are quotes from the report:

“The country between Warsaw and Moscow can be divided in three distinct parts separated from each other by large rivers or by old political limits recent changed by a great usurpation but which remains in the hearts of the inhabitants of old Poland.”

“The first part enclosed by the Vistule and the Niemen has 77 leagues of length, and the Neiman has 77 leagues of length. The route that goes through it passes by a good number of little towns, among them, the towns of the route that goes through it passes by a good number of little towns, among them, the towns of Siroska, Pultuska, Ostrolenka, and Byalistok are the largest.”

“The second from Grodno to Orzay has 125 leagues. It includes old Palatinate of Troki, Minsk, part of that of Vitebsk, all the high parts of the Niemen and also those of the Dnieper to the right bank of the Pleure beyond which starts the Russian government of Smolensk. The route passes by the towns of Norogrodek, Mir, Minsk, Barisow, Toloezinn, Orzay and Doubrovka.”

“The third part between Smolensk and Moscow is entirely in old Russia. It’s length by the route is 131 leagues. One finds in succession, the towns of Dorogouer, Viarnie, Gradsk, and Moyaiska. This last part is the most fertile and the most populated.”

“All these countries present more or less the same aspect. There are still immense plains in which the slopes are nearly undetectable, and which offer everywhere swamps and prairies, grand forests of birch and fir trees, sandy fields…”

“Care is particularly necessary, and the third part which forms a sandy field elevated between the sources of the Duna, the Dnieper, the Locka and the Volga. From Warsaw to the Dnieper at Orzay the routes are generally very difficult for the carts and because even impassible at a great number of points during times of thaw and great rains. It would be necessary to make them viable in these seasons by burying a part of the wood found there. A regular system of works would find few difficulties in the execution because the Polish countrymen is accustomed to it and their hatred toward Russia would serve them to work in the hopes of a return to the former limits….

“Resources for provisioning are unequally spread along this long route. Strong and vigilant administration would certainly succeeded in nourishing a grand Army from Warsaw to Norogrodek. But the swampy forests of the government of Minsk offers only a few groups of large cattle. And difficulties of all types become their much larger and more numerous than any other part. It is necessary that the fertile government of Vilna suffices. In any case, one no longer finds to the right of the route, anything except immense swamps of Pinsk, on which one must travel by boat during half of the year. One only exits this beyond Toloczinn, a small town distance from Minsk by around 40 leagues….”

The manuscript continues to discuss the dedication of national spirit “in all classes”. Only the poorest nobility, it states, would want to join the Russian Army. Many, it continues, are unmoved by any advantages offered them by Tsar Paul I (ruler until 1801) and “remain far from all public functions, and hide very poorly their aversion for anything Russian. All the officers of the government are forced to live completely isolated. Beyond Toloczinn, the columns would march with ?, along the beautiful routes of the government of Smolensk and of Mohilow, both abundant with grain and cattle.”

One finds still fewer animals approaching Moscow, and this town pulls all its provisions of cattle from Ukraine, and above all from the government of Pultava.

“The river passages are many, but the majority are easy to execute because beyond the Vistule, one finds no longer any impediments. Nearly all the bridges are firm… Pontoon bridges could nearly everywhere be employed, at least for the passage and movement of artillery and field baggage, because the rivers have such a tranquil course that the pontoons could be very close to one another without causing any accident.”

“The best points of passage are:”

The manuscript now moves to the rivers and the possible bridge crossings of Warsaw, Syroska, Ostrolenka, Tykoczinn, Grodon, Barisow, Orzay, and Smolensk. This includes the Dnieper and Vistule and other waterways, along with the size and strength of the bridges.

“Itinerary from Warsaw to Moscow by Grodno and Smolensk”

The bulk of the manuscript begins here by listing the post stations of locale, along with its distance (in the antiquated Russian measure of Werstes and also in Leagues) and population (in number of houses). This is accomplished using a charge, which lists, left to right, distance, name of location, number of homes, and ‘observations.’ The indication of the number of houses of each one is only an approximation and relates solely to groups of habitations that could be perceived on the route.

What follows is a remarkable 5 two-page spreads of each station between Warsaw and Moscow, with observations intended to instruct an invading army. They are at once military observations and a fascinating cultural, demographic and geographical account of the region. The names are in some cases obscure or antiquated spellings, including Moscow, which is Mouscou and not Moscou, as one would expect in French.

Manuscript: The manuscript begins in Warsaw, or Varsovie: “In leaving Warsaw, one crosses the Vistule on a boat bridge. The length of the river is around 300. It is very quick, the banks are accessible and a little elevated….” The manuscript notes it is a town of 10,000 houses.

The march to Russia: On June 24, 1812 and subsequent days, the initial wave of the Napoleon’s Grande Armée crossed the Niemen River, marking the entry from the Duchy of Warsaw.

Manuscript: Trezel notes that at Miaskovo, in Poland still and beyond Ostrolenka, “The Russians had established a hospital for 300 sick”. The next large town is Bialystock. Here he notes “A great village named Vassilkoff around halfway down the path from Bialystock to Boukstell. The path is in a sandy plain for an hour, after which one passes on a fixed bridge over a river of 25 toises of length with a reed rope… The final league is follows on the right a sandy and rocky field. They have planted ash and other trees. Two batallions of grenadiers were camped a half league from Trokolska.”

The chart now takes us into Belarus and toward Grodno. “Grodno is an open town on the right bank of the Niemen. To enter, one crosses the river on a large boat bridge… The banks are strongly inclined…Immediately above the bridge on the right is a large amphitheater surrounded by homes…. One sees on the other side of town on the right and to the left of the route from Smolensk ruins of defensive fortifications…. It is fertile in grain.” The manuscript notes 2000 houses.

The march to Russia. On July 1, Jerome Bonaparte’s right flank crossed the Niemen at Grodno. The VII Corps stayed in the Grodno region to protect the Duchy of Warsaw.

The manuscript: “There are many swamps between Lyda and Lipini. Exiting Lyda one crosses a bridge in the middle of which is an old ruined chateau. The post house of Lapini is immediately beyond a river of 16 or 17 toises…One crosses the bridge on a large square boat that could carry two strong carts.”

The march to Russia: On June 27, the Russian corps, stationed between Lida and Grodno, was almost cut off by the Grande Armée’s crossing of the Niemen and Gen. Davout’s troops making for Minsk.

The manuscript: “Mir is the last town of the government of Grodno. I did not enter here because the post is outside and near an old abandoned chateau belonging to the Prince of Radniville. It is flanked by 4 paths a grassy rampe. The door has been removed the rest falls into ruins.”

The march to Russia: With Jerome’s troops trailing the retreating Russian Army, Platov’s cossacks ambushed Jerome’s advanced Polish lancers on July 8 – 10, near the village and Mir. These clashes were the first real combat of the campaign, and saw the Polish troops defeated.

The manuscript: “Minsk is a town of 10,000 inhabitants of which two thirds are Jewish. It is located on a little river of 20-35 toises of length bordered by a lovely promenade. One crosses on a good bridge. The roads are straight and wide and the houses spaced between each other. They are nearly all in wood…. The territory is without comparison the worst path of those that one pases to go to Moscow. The population has retained the Polish cavalry. The entire population of all classes retains the most pronounced aversion to the Russians. There are only the poorest nobility who wanted to take up service.”

The march to Russia: On July 8, Davout’s troops reached Minsk. He lost many troops on the way there. Large store houses were constructed here.

The manuscript: “We are approaching Russia. Near Zadinn and Barisow, he notes the river Bereczina, whose “right bank forms an sandy escarpment of which the slope is steep but practicable to cars. There is on this bank a settlement of around 30 homes. I found there an artillery park of the 25th miitary division (Siberia).”

In approaching Smolensk, he passes through a tiny town he calls “Reritnia.” He notes a rampart “flanked by by a few towers. Its height is around 30 feet and thickness around 6 feet at most. It is entirely vested and supported in the interior by brick arcades. It’s only defense would be a fusillade by the large pines that crown it and one could ruin this all in less than one hour with canons. One would seize very easily the high neighborhood and two beautiful churches, one of which is surrounded by a wall crenelated with bricks. The passage from the Dnieper would not present much difficulty because one could crush anyone who remained in the settlement on the right bank.”

The march to Russia: On the afternoon of August 15, troops under Murat and Ney arrived at the western edge of Smolensk. Over the course of the next two days, Ney’s and Murat’s troops, along with Poniatowski’s Polish Corps, clashed with the Russians pitched in Smolensk. About 11,000 Russians died defending the city, which fell to the French and was a major depot for the troops heading east.

The manuscript: “Moscow is enclosed only an earthen rise of 3 feet in height. One could attempt to defend the passage from Moskova… but this resistance could only result in the burning by the assailant of a large part of the wooden houses of Moscow. One could hold up there peacefully occupying the interior chateau called the Kremts [Kremlin] which is situated on the Moskwa more or less in the middle of the town. It contains 2 churches, the arsenal, several considerable columns.”

The march to Russia: On September 14, the French entered Moscow, only to find it abandoned. All but a few thousand of the city’s 275,000 people were gone. Napoleon retired to a house on the outskirts of the city for the night, but two hours after midnight he was informed that a fire had broken out in the city. He went to the Kremlin, where he watched the flames continue to grow. Reports began to come in telling of Russians starting the fires and stoking the flames. Suddenly a fire broke out within the Kremlin, apparently set by a Russian military policeman who was immediately executed. With the firestorm spreading, Napoleon and his entourage were forced to flee down burning streets to Moscow’s outskirts and narrowly avoided being asphyxiated. When the flames died down three days later, more than two-thirds of the city was destroyed. The images of Moscow on fire are iconic; many great works of art depict the event.

The 14-page manuscript is an extraordinary piece of history, the survival of which was unknown until now: notes used to plan and help guide Napoleon and his Grand Armees in their invasion of Russia.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services