The Original Implementation Order Expelling the Jesuits From Spain’s Possessions in the New World in 1767

It changed the New World: King Charles III notifies officials in Spanish America that he has suppressed the Jesuits, who had a dominant position there, and that they are to be removed from his domains and their vast possessions confiscated

“Motivated by grave causes related to my obligation to maintain my people in subordination, tranquility and justice, as well as other urgent, just and necessary reasons that I reserve to my Royal self: I have decided to order removed from all my dominions in Spain and the Indies, and the Philippine Islands...

“Motivated by grave causes related to my obligation to maintain my people in subordination, tranquility and justice, as well as other urgent, just and necessary reasons that I reserve to my Royal self: I have decided to order removed from all my dominions in Spain and the Indies, and the Philippine Islands and adjacent dominions, all members of the Company of Jesus…” – This removed the Jesuits as a factor in North America in the era that saw the establishment and expansion of the United States; It paved the way for the Franciscans in California

The Society of Jesus – or Jesuits – was founded in 1534 by Ignatius of Loyola, a Spanish soldier. Following a religious awakening while recovering from wounds, Ignatius gathered a group of dedicated followers who pledged themselves to lives of poverty and chastity. In 1540, the group received a charter from Rome in which the members promised total loyalty to the Pope and a willingness to go wherever he might assign them. The Jesuits made their initial impact by combating advances made by the Protestant Reformation. Within a short period of time the order grew to thousands of dedicated men, many of them the elite of the European intelligentsia at the time. They were highly educated in many fields, and characterized by their dedication, willingness for self-sacrifice, and determination to spread the faith; they were a key Catholic weapon for evangelization. Over the next two centuries the order grew and extended its influence through its roles in education, scholarship, and missionary activities. Schools, colleges, universities, and seminaries were established in nearly all of the great urban centers of Europe, and missions were founded in such faraway locations as India, Japan, China, and the Americas.

As early as 1549 the Jesuits sent their first missionaries to Latin America, to Brazil. Jesuits arrived in Mexico and Peru in 1568, arriving on the ship bearing Peru’s most important viceroy, Francisco de Toledo. As a newly founded order, untainted by the abuses that had affected older orders in the Catholic Church and fired with the enthusiasm of fresh troops, the Jesuits built schools and founded missions everywhere, from Mexico to Chile, from Brazil to Paraguay. They became the most influential order in Latin America, and their schools flourished and missions prospered. They actively evangelized the Indians and organized settlements for them. For example, a little over 100,000 Guaraní Indians in Paraguay and another 100,000 Indians in Bolivia lived in neat towns established by the Jesuits. A sort of priestly protectorate ruled over the native tribes where the Jesuits ruled, as they protected the natives in these places from slavers who sought to kidnap and sell them. By the mid 1600s, the 336 Jesuits in Mexico administered the most admired colleges and seminaries. By 1767 there were 678 Jesuits. They owned and operated 24 colleges, 11 seminaries, 102 missions and 27 strategic haciendas that provided income for their various projects. There were 17 missions in California.

By the middle of the 18th century the Jesuits worldwide consisted of 24 professed-houses, 369 colleges, 170 seminaries, 61 novitiate-houses, 335 residences, 273 missions in heathen and Protestant countries, and 22,589 members of all ranks, half of whom were ordained priests. There was not a country, no matter how remote, or difficult of access, where they were not at work. The society possessed immense wealth; it controlled to a large extent the education of rich and prominent youths in many countries, and its members were the confessors of kings and princes. It exerted a powerful political influence in the civil administration of Catholic countries. In fact, in Spain in 1765 some 80 per cent of people in public office, such as councillors and judges, were ex-students of the Jesuits. In Spanish America the Jesuits main activity involved educating elite criollos (American-born Spanish men), some of whom themselves became Jesuits. So the Jesuits had power, influence and money.

This very success excited the jealousy and distrust of important people. Monarchs in many European states grew progressively wary of what they saw as undue Jesuit influence over their affairs, and and saw the Jesuits as impediments to their desire for autocratic power. They were familiar with the Enlightenment anti-clerical ideas, and saw with envy how the Anglican Church in Britain had been made independent of Rome and subservient instead to its king; it had effectively been incorporated into the State. The Jesuits, with their vow of obedience to the Pope, and their reputation for non-conformism, strongly opposed regal absolutism and the monarchists who sought to promote it. Monarchists in turn saw the Jesuits as a threat and were suspicious of their loyalty. In addition, the Jesuits were accused of converting their missionary stations into commercial centers and of conducting – in some cases dominating – business in a way that solely benefitted them. It was also alleged that they avoided the payment of required tithes by false representations of the conditions of their missions—a claim that the Franciscan friars, the order that would most benefit from the fall of the Jesuits, first brought to the attention of Spanish royalty. If the Jesuits were gone, powerful people in Catholic countries began to think, there would be no impediment to royal power, and their riches could be confiscated by the king and distributed as he saw fit.

The Jesuits were suppressed in Portugal and its colonies in 1759 and in France and its colonies in 1764. But the greatest blow to the Jesuits would come in Spain, which was then a wealthy country with far-flung possessions. There, in 1766, in the wake of unpopular government economic measures, there were riots, and attacks on the government were published. This was the pretext that anti-Jesuits had been looking for; and an extraordinary council was appointed to investigate the matter (and it was declared that people so simple as rioters could never have produced the political pamphlets). The council proceeded to take secret information, and it centered on the Jesuits. By September 1766, the council had resolved to incriminate the Jesuits, and by January 29, 1767, their expulsion was settled.

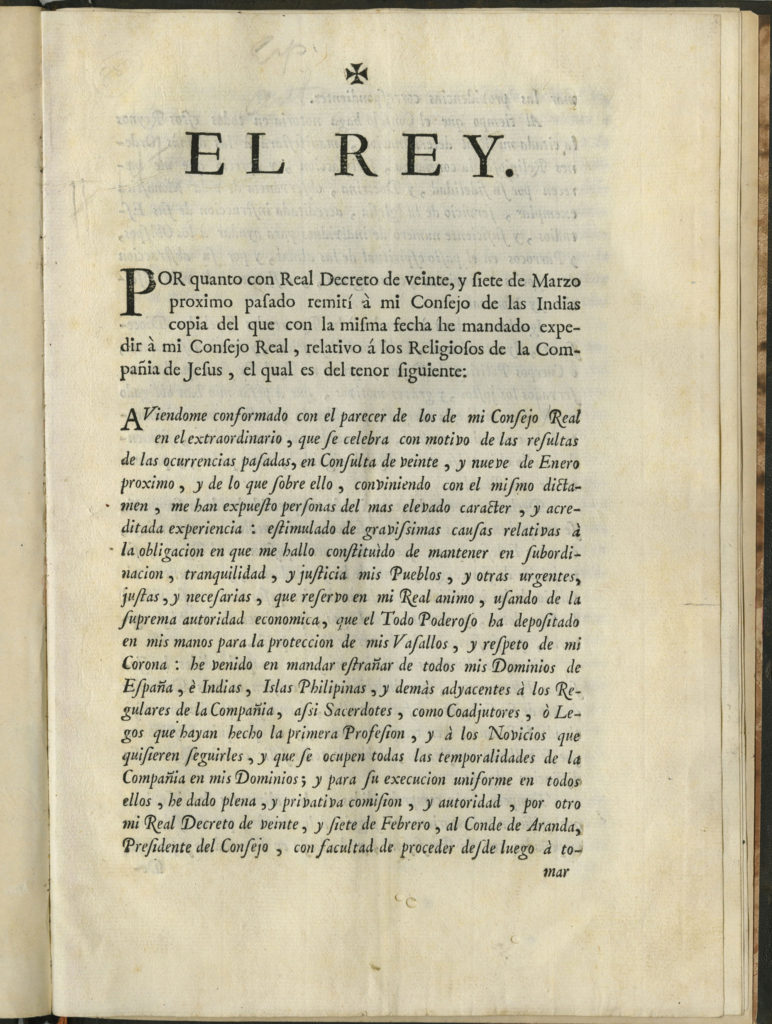

On March 27, 1767, King Charles III issued a royal edict ejecting the Jesuits from Spain and its possessions (though refusing to cite his specific reasons). He decreed: “Motivated by grave causes related to my obligation to maintain my people in subordination, tranquility and justice, as well as other urgent, just and necessary reasons that I reserve to my Royal self: l have decided to order removed from all my dominions in Spain and the Indies, and the Philippine Islands and adjacent dominions, all members of the Company of Jesus, as well as priests, coadjutors or lay brothers who have made their first vows, and any novices who wish to follow them.”

Orders were sent to all provincial viceroys and district military commanders in Spain. They received a copy of the original order expelling all members of the Society of Jesus from Charles’s domains and confiscating all their goods. Another enclosure instructed local officials to surround the Jesuit colleges and residences on the night of April 2, arrest the Jesuits, and arrange their passage to ships awaiting them at various ports. King Charles’s closing sentence read: “If a single Jesuit, even though sick or dying, is still to be found in the area under your command after the embarkation, prepare yourself to face summary execution.” The plan worked smoothly. That morning, 6000 Jesuits were marched like convicts to the Spanish coast, where they were deported, first to the Papal States and ultimately to Corsica. That took care of matters in Spain proper.

Now for the Spanish overseas possessions. On April 5 Charles signed an order to implement the expulsion of the Jesuits from his dominions in the Americas and the Philippines, one that a Jesuit scholar informs us “goes into detail about how this should be carried out.” In it he recites his March 27 decree and states he wants it complied with completely and expeditiously. Printed copies of that order – signed by the King – were sent to the royal governors and major colleges, churches and monasteries in the Americas. Probably a few score of these printed orders were sent out, though our research discloses none having reached the public market.

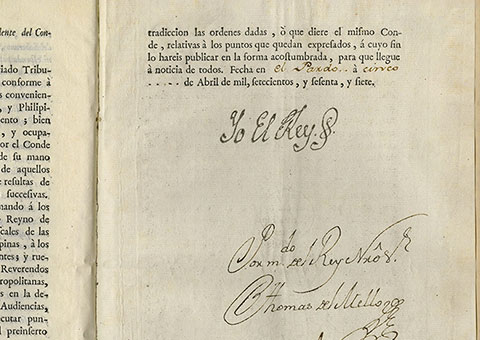

Document signed by the King with his stamp, the royal palace of El Pardo near Madrid, April 5, 1767, being one of the original signed implementation orders sent out on that day. It is countersigned by the Secretary of the Office of the Indies, Thomas del Mello, and has the rubric autographs of the King’s counselors as well. We have searched for any surviving copy of this signed order having reached the public market, but cannot find any.

The decree and implementation order arrived in Spanish America in June, though not reaching California until November. When it did, Spanish soldiers removed the Jesuits from their missions and stations. An estimated 2,700 Jesuits were sent into exile. About 2,300 Jesuit missionaries from South America and the Philippines travelled to Europe, mainly ending up in the Papal States. In total, 188 colleges closed down, the experiment of communal villages for Indian Christians was ended, and Jesuit property was confiscated everywhere. Mexico is a typical case study. Of the 678 Jesuits expelled from there, 75% were Mexican-born. No Jesuit, no matter how old or ill, was excepted from the King’s order. Many died on the trek along the cactus-studded trail to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, where ships awaited them to transport them to Italian exile. There were protests in Mexico at the exile of so many Jesuit members of elite families, but the Jesuits themselves obeyed the order. Since the Jesuits had owned extensive landed estates in Mexico – which supported both their evangelization of indigenous peoples and their education mission to criollo elites – their properties became a source of wealth for the crown. The crown auctioned them off, directly benefiting the King and treasury. The expulsion of the Jesuits left a vacuum in Spanish America that the Dominicans and Franciscans rushed to fill, thus expanding the power and reach of those orders. When the United States took possession of California, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas, they found Franciscans, whose interest centered on ministering to the poor, rather than Jesuits, who would have doubtless been spiritual warriors with a greater interest in the affairs of business and government.

The Jesuits could look back on a series of major accomplishments in the New World. Their mission stations served the indigenous population in the Paraguay towns, in the Andes, in the Amazon, in Colombia, in Mexico and California, in the growing urban areas, and on the rural farms and ranches that they administered. The number of conversions made, baptisms administered, and marriages performed were all recorded by those who measured success by numbers, and each year a tally was sent from America to the central Jesuit office in Rome. The number of Indian villages and communities that remained within the Christian fold over long periods of time is significant. Every village in the Andes had its patron saint, its fiesta. The Jesuits could also count the number of colleges and universities they administered and in which they lectured. The elite and future priests were often Jesuit alumni. From their pulpits the Jesuits preached abnegation, penance, love, faith, the virtues, what they thought a good Christian should be and how they should act. This was, perhaps, their greatest legacy.

On the other side of the coin are the activities about which the Jesuits should not have been proud. Their own superiors questioned what they called an over-concern with material things. Their very success as farmers, ranchers, and traders roused the enmity of the lay businessperson. The nature of the Spanish imperial system allowed the Church prerogatives and influence that few laypersons possessed, thus giving the Jesuits preferred positions. And the Jesuits used black slaves to run their sugar estates and other properties, which the Jesuits acquired in order to finance their schools.

In 1814 the Jesuits were restored as an order, though their property was gone, their records were dispersed, and there was a serious shortage of manpower. They rose again, though not to their previous position of power and wealth. Today have some 22,000 members.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services