Daniel Webster’s Last Autograph Letter Signed Known to Be in Private Hands

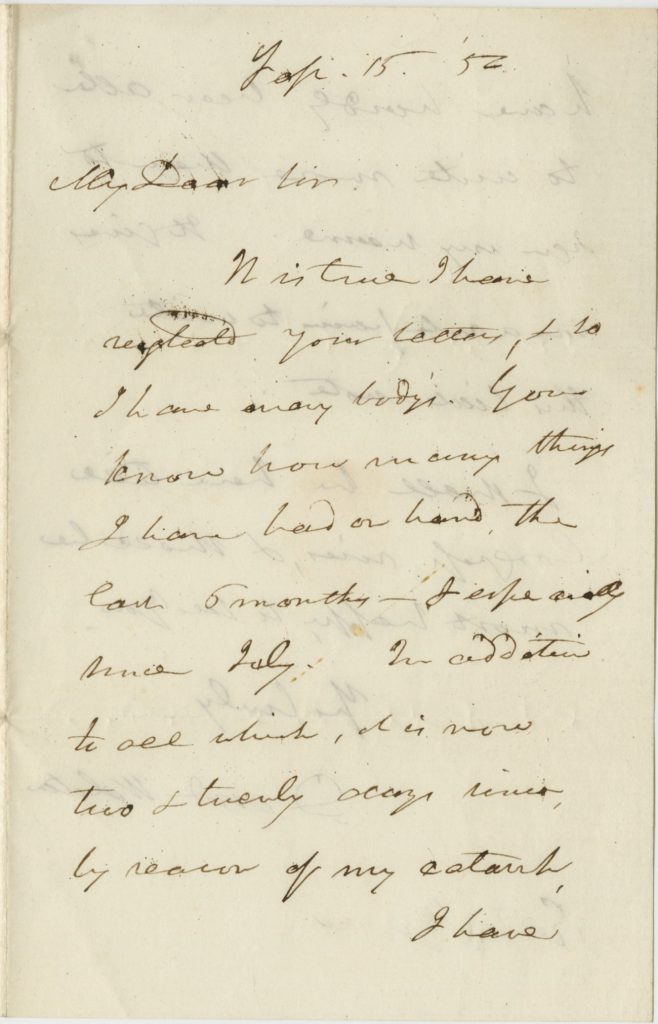

The dying orator writes, "I have hardly been able to write more than to sign my name. It gives me acute pain to write this little note.".

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

After two terms in the House of Representatives, Webster became a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts and served until 1841. He became nationally famous in 1830 for his thundering defense of the Union in his replies to South Carolina Sen. Robert Hayne during the first states’ rights controversy, and was the acknowledged leader...

After two terms in the House of Representatives, Webster became a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts and served until 1841. He became nationally famous in 1830 for his thundering defense of the Union in his replies to South Carolina Sen. Robert Hayne during the first states’ rights controversy, and was the acknowledged leader of the North during the Nullification Crisis that followed. He returned to the U.S. Senate from 1845 to 1850.

Webster served as Secretary of State to Presidents William Henry Harrison and John Tyler. In this post, his major task was to resolve a number of longstanding disputes with Great Britain that might have flared up into war. He helped achieve the landmark Anglo-American Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842 that settled the Maine boundary, increased U.S. involvement in suppressing the African slave trade, and included an extradition clause that would become a model for future treaties. The agreement also ushered in an era of rapprochement between the two nations, allowing the U.S. government to focus on westward expansion. Webster also extended diplomatic protection to U.S. missionaries abroad, and sent the first U.S. mission to China. He resigned from the Secretaryship in 1843 due to a disagreement with President Tyler over the annexation of Texas, a move stridently opposed by Webster. Webster returned to the Senate from 1845-50, and in the latter year was the primary Northern voice calling for passage of the Compromise of 1850 despite its containing a Fugitive Slave Law. After President Fillmore brought him back as Secretary of State in July 1850, Webster dedicated significant attention to getting the Compromise through Congress and then justifying it in the North. Webster also continued to support rapprochement with Great Britain, and advocated the establishment of commercial relations with Japan, going so far as to draft the letter that was to be presented to the Japanese Emperor on President Fillmore’s behalf by Commodore Matthew Perry on his 1852 voyage there.

The Whig party was bitterly divided in the 1852 election. The incumbent president, Millard Fillmore, seemed a candidate for reelection, but then tried to withdraw, then withdrew his withdrawal. In any case, he had little support in the North because of his advocacy of the Compromise of 1850. Webster wanted the job, but his main base of support was New England, and even here many Whigs who previously supported him were hesitant because they felt betrayed by the Compromise of 1850. Gen. Winfield Scott was a favorite of many, mainly because he was a Whig from the South who might win, and whose military career meant he had made few political enemies. At the Whig Convention in June, Scott emerged as the nominee. A month later, the American Party (remembered in history as the No-nothings), nominated Webster for President. Furious at the Whigs, Webster would not refuse the American nomination nor endorse Scott.

Webster suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and other ailments. As Robert Remini writes in his biography “Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time”, “Webster’s health declined rapidly in September, and his Boston physician, John Jeffries, visited with him several days and conferred with a local doctor, John Porter.” They brought in a specialist, who told them Webster’s case was mortal, and Webster himself came to suspect that he was dying. This significantly affected his correspondence, as he was no longer able to do much writing. He stopped writing out letters in full, and began having them prepared by secretaries for his signature. Thus, he switched from ALS mode to LS.

On September 15, 1852, friends of Webster met at Faneuil Hall in Boston to drum up support for him. That same day Webster wrote this Autograph letter signed, two pages. “It is true I have neglected your letter, & so I have everybody’s. You know how many things I have had on hand, the last six months, & especially since July. In addition to all [this], it is now two and twenty days since, by reason of my catarrh, I have hardly been able to write more than to sign my name. It gives me acute pain to write this little note. I shall be here till Congress rises, and shall be most happy to see you.” Catarrh is a disorder of inflammation of the respiratory tract.

Our research indicates that this was Webster’s last known ALS that remains in private hands. After writing it, his condition continued to worsen throughout the following month, and his activities were more and more circumscribed. By mid-October he was sinking fast, and he died on October 24, 1852.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services