Part 1 of the story of the Crawford collection

A distant late summer storm rolled north over Montgomery, Alabama, far enough away from our plane to not disturb our flight but close enough to be beautiful, as we landed at Golden Triangle Airport. If you have ever been to Mississippi State University, you might have used this airport, but otherwise there is not much call. The University was not our destination for this trip. Steven, Karen, and I were headed to a small hotel outside Starkville for a good night’s sleep and the following day, though we did not yet know it, to see one of the great undiscovered collections of American historical treasures.

Months earlier, in our offices in suburban Philadelphia, we received a call from a soft-spoken man with a gentle southern accent, informing us he had a collection with several letters of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. He was a descendant of the recipient, he said, whom he identified as William H. Crawford, an important 19th century politico, and said he heard we worked with people like him. He thought his collection might have some value. He claimed, without pomp, without flair, without even changing the subdued inflection in his voice, to have hundreds of pieces. My first reaction: I’ll believe it when I see it. We get many calls and emails every day from people believing to have this or that and often they don’t. I cannot tell you how many people have offered me Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in the last calendar year alone. I recall getting off the phone with him and, in more or less the same tone he had used with me, called the team and, among other things on the agenda, informed them that, “Some man called and he says he has a bunch of Jefferson-era documents…we’ll see.” "Yeah we'll see," said my dad with a chuckle.

Months later, we woke up at our rural hotel. The restaurant’s breakfast was a muffin and fruit, alongside a massive statue of the University’s bulldog mascot, and tables packed with alumni in town for a football game. I went for a jog along the main road, which wove back behind the hotel and uphill toward the town. A quiet, beautiful morning, crisp but an early fall crisp, and warm enough to really enjoy. I put on my suit and we assembled in the parking lot. Our destination: a bank, or rather, a private room in a bank. The man with the soft spoken voice, who we will call Bill, appeared in person, meeting us at the door, wearing khaki pants and a green button down shirt. He led us upstairs, past offices, to a small conference room, where his wife waited there for us, seated at a circular wooden conference table that took up around 1/2 the room. She rose slowly, shook hands, and began helping her husband.

What waited for us? 26 binders, labeled alphabetically by letter, arranged carefully on a side table in order from A to Z. He was wearing white gloves, which we told him was not necessary. In fact, touching with bare hands is preferable. We chuckled, exchanged pleasantries, and then began.

It is important to know that we would not have made the trip down to Mississippi had we not felt that he had something worth seeing. But each time we walk into a stranger’s home or to see a collection for the first time, we temper our excitement with the knowledge that we don’t really know what they have until we see it with our own eyes. Are these reproductions, copies? Was the whole thing just a facade? So what did we know prior to going down? We had seen an inventory of the supposed collection, heard his claims to be the direct descendant of the historical figure, and had seen seven relatively primitive photocopies of a few pieces he had selected.

With this as the backdrop, Bill handed us the first binder. I say binder but really they were portfolios, black in color, with large plastic sleeves holding the documents. There were two documents per sleeve, facing opposite ways, and separated by a black liner. In a pocket on the inside cover, he had listed every piece in the binder, when he was able to identify them. It did not take long to get to the good stuff. I opened the first binder and the very first piece I saw was a letter of the Duke of Wellington. I read it slowly. Wellington's hand writing can be nearly indecipherable. It was a letter announcing the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, America’s first treaty under the Constitution. I carefully removed the letter, ran my finger over it, looked closely at it, held it up to the light, smelled it, and just took it all in. This was no copy: it was the real thing. I passed it around the table, first to Karen, then to my father, and all concurred.

I turned to Bill and his wife and asked, “Did you know you had an important letter of the Duke of Wellington?” Bill sort of nodded his head, smiled, and could see we were enjoying ourselves. They knew something that was just dawning on us: an entire museum lay hidden in the plastic sleeves of these 26 binders, a museum that had been outside the view of scholars for generations.

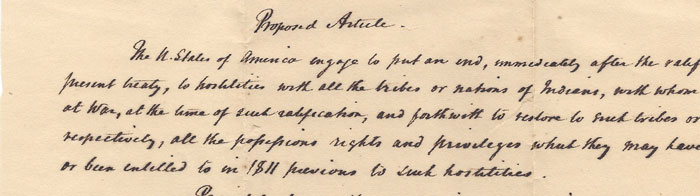

The same thing occurred hundreds of times that day, over the course of five hours: a piece was examined, passed around, read. There were letters of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, the Marquis de Lafayette, and others. In one binder, he listed the content of one sleeve as simply “Proposed Article.” What was this? The handwriting looked awfully familiar. It was. It was Article 9 of the Treaty of Ghent entirely in the hand of Henry Clay. Another piece he had labeled with a question mark. But it began with the words “The Chief Justice.” Could this be in the hand of John Marshall? It was – an important opinion entirely in his hand, written to Crawford as Secretary of the Treasury. Both men have remarkably distinguishable handwriting: Marshall wrote in thick, bold, dark handwriting. His letters often have deep show-through from one side to the other, the result of his heavy pen. Clay, by contrast, has thin, neat handwriting.

I recall Karen smiling broadly and my father’s chin nearly touching the ground with amazement. We were in the presence of history and watching it unfold in real time as Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Clay, Adams and Crawford did over 200 years ago.

Where had these pieces been all this time? “Oh,” he said, “they were in a box in my mother’s house and a few years back I put them into binders. I hope you like them.” A typical understatement from Bill.

That evening, I had my first Southern BBQ. I barely knew how to read the menu but it was really good. We waited in a brief line and ordered from a menu with 400 fried items. The seating area was nice and overlooked an area that felt like it might be full with live music and Miller Light at happy hour time. They called our name and brought our fried food of choice. And boy was it tastey. Bill and his wife described how they met, how they hoped to retire and travel, and we told them about our family, our family business, and how our summer had gone. We barely discussed the collection, though it was on our minds. Our work was about to begin. We had to negotiate the purchase, sort through the mass of materials, and transcribe and describe hundreds of historical documents, most unpublished. This is yet another story.

When we dropped off our rental car the next day, I recall telling the team, “That collection belongs with us.” It gives me satisfaction to think that Bill and his wife are enjoying their retirement and we are finding these documents new homes, many of them in institutions where they will be publicly studied and others in serious private collections, where they will be loved, enjoyed, and preserved.