Gen. Winfield Scott Laments the Death of His Old Friend, Roger ap Catesby Jones, Adjutant General of the U.S. Army, With Whom He Had Served For 30 Years

He writes, “You must all be of good cheer. Providence will not allow the good to suffer.".

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

Scott fought on the Niagara frontier in the War of 1812, was captured by the British in that campaign during the Battle of Queenston Heights in 1813, but was released in a prisoner exchange. In March 1814 Scott was brevetted brigadier general. In July 1814, Scott commanded the First Brigade of the...

Scott fought on the Niagara frontier in the War of 1812, was captured by the British in that campaign during the Battle of Queenston Heights in 1813, but was released in a prisoner exchange. In March 1814 Scott was brevetted brigadier general. In July 1814, Scott commanded the First Brigade of the American army in the Niagara campaign, winning the Battle of Chippewa decisively on July 5, 1814.. He was wounded during the American defeat at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane (july 25), along with the American commander, Major General Jacob Brown and the British/Canadian commander, Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond. As the American army retreated across the Niagara, Scott commanded the American forces at Fort Erie, another American victory. Scott’s success on the Niagara, combined with American naval victories at Lake Champlain and Lake Erie, guaranteed a stalemate on the northern frontier. Scott’s wounds from Lundy’s Lane were so severe that he did not serve on active duty for the remainder of the war. But his successes had made him a national hero.

Scott remained in military service after the war, studying tactics in Europe and taking a deep interest in maintaining a well-trained and disciplined U.S. Army. He earned the nickname of “Old Fuss and Feathers” for his insistence of military appearance and discipline in the U.S. Army, which consisted mostly of volunteers. In his own campaigns, General Scott preferred to use a core of U.S. Army Regulars whenever possible. In 1841, he became commanding general of the United States Army, and served in that capacity until 1861.

Roger ap Catesby Jones served with Scott in the War of 1812. He had caught the eye of General Jacob Brown, who brought Jones into his staff as his assistant adjutant general prior to his 1814 Niagara campaign. As Brown’s adjutant, it was Jones’s responsibility to collect and retain records, determine and detail casualties, manage correspondence, work with or supervise the other adjutants, and see to it that significant information and statistics were reported back to the War Department in Washington. In this capacity, he came to know Scott, and the men began a lifetime friendship.

Jones fought conspicuously on July 5, 1814 in the victory at Chippewa, and was personally commended by Brown for his performance at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane on July 25. For these, he won a brevet promotion to major. He next served at the defense of Fort Erie on August 14, and received commendation from General Edmund Gaines. A month later, on September 17, he was involved in the sortie from Fort Erie, and performed so well he was given a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel. Meanwhile, Jones prepared and sent reports of killed and wounded in the Niagara campaign to the War Department in Washington. He retained the originals of the reports and some copies for his own records as Adjutant General in the field.

In 1815, after the war, Brown had Jones join him as aide-de-camp and adjutant general. In 1818 Jones became a brevet colonel and then accompanied Brown on a tour of the Northwest defenses. In March 1825 he was appointed Adjutant General of the U.S. Army, a post he held for a record 27 years until his death. He was brevetted brigadier general in June 1832, and major general in May 1848.

As the Army’s overall chief of staff during that period, Jones was responsible for recruiting, training and administration. He worked with the Army’s commanding general, which until 1828 was Brown. After a period of contention with Brown’s successor, the top general’s post was assumed by Jones’s trusted friend and colleague Winfield Scott, who had fought with him in Canada, and they worked closely together to maintain the autonomy of the Army from bureaucratic intrigues. The Jones era is remembered for the reforms he introduced that modernized the Army. He died on July 15, 1852. President Fillmore was among the notables to attend his funeral.

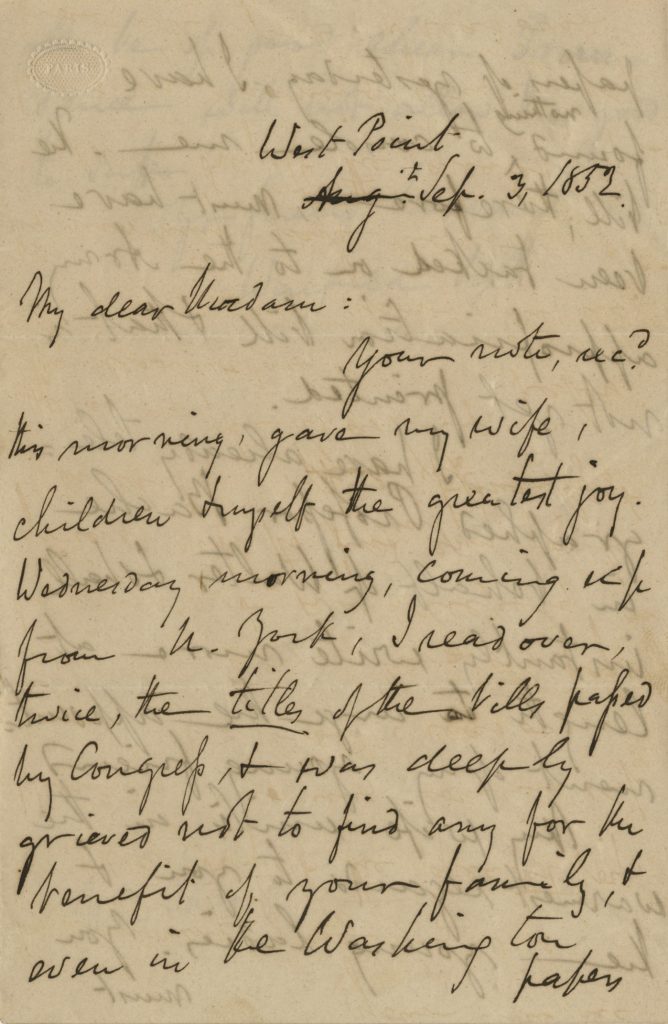

Autograph letter signed, West Point, NY, September 3, 1852, to Mrs. Jones. “Your note, received this morning, gave my wife, children & myself the greatest joy. Wednesday morning, coming up from N. York, I read over, twice, the titles of the bills passed by Congress, & was deeply grieved not to find any for the benefit of your family, & even in the Washington papers of yesterday I have found nothing to console me. The bill, therefore, must have been tacked on to the army appropriation bill & that is not yet printed. I have already telegraphed Professor Bache in behalf of Walter & shall instantly write more at length to urge the appointment of my young friend. My wife unites in the warmest regards to you & the young ladies. You must all be of good cheer. Providence will not allow the good to suffer.” With its free franked envelope.

Professor Alexander Dallas Bache was a scientist and surveyor who erected coastal fortifications and conducted a detailed survey mapping of the United States coastline. Mrs. Jones’s son, Walter Charles Jones, graduated 1853. was studying engineering at VMI, and was graduating in 1853, so an introduction to Bache made good sense. Walter ended up as an officer in US Army. When Virginia seceded, he resigned his commission and became an officer in the Confederate service.

As for the bill to give relief to Mrs. Jones, it was not until 1856 that Congress approved it.

This letter was part of the Roger Jones papers we have acquired, and has never before been offered for sale.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services