Gen. William T. Sherman Admits He Is Struggling to Adjust From the Swirl of Active Wartime Activity to the Tedium of Peacetime

In this unpublished and previously unknown letter, he confides that he finds life dull, that it is “hard work to keep still”, and he can “only exist” imagining future hoped-for exploits.

With the end of the Civil War, Congress reduced the size of the U.S. Army from over one million men to 54,000, and required that force to man 255 military posts scattered throughout the nation. Political pressure continued to whittle away at the army until it was composed of 25,000 men.

...

With the end of the Civil War, Congress reduced the size of the U.S. Army from over one million men to 54,000, and required that force to man 255 military posts scattered throughout the nation. Political pressure continued to whittle away at the army until it was composed of 25,000 men.

Sherman had commanded 60,000 men in one concentrated force in a time of active war. His life, and those of his comrades in arms, was all animation, pressured decision-making, elation, gloom, movement, exhaustion, pathos, comradeship – and it was all immediate. After the Grand Review in Washington on May 23-24, 1865, Sherman’s army was discharged, and he went West. On June 7 he spoke at the commencement exercises at Notre Dame College, a school much beloved by his wife. He returned to St. Louis in July to take command of the peacetime Military Division of the Mississippi. His new command encompassed everything from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, thousands of miles in all directions, which were manned by just a small fraction of the army’s total men, with no large centers of troop concentration. His was essentially a desk job, in that he moved papers and telegraphed orders to small units of men great distances apart.

Gen. David S. Stanley commanded a division under Grant in the West, and was promoted to major general in 1863. He served as one of Sherman’s corps commanders in the Atlanta campaign. He played an important role in the victory at the Battle of Franklin, where he was wounded. Stanley’s 4th Corps was deactivated in August 1865, but rather than mustering out, it was sent to Texas as part of the U.S. Army detachment dispatched to persuade French Emperor Napoleon III to withdraw his troops from Mexico. It was not disbanded until December 1865. Then, finally, Stanley got home. He hoped, like Sherman, to remain in the Regular Army, and wrote to his old commander about securing a position in the shrinking force, something that would not be easy, even for a seasoned general such as himself. He also conveyed to Sherman the problem he was having adjusting to peacetime after the swirl of war.

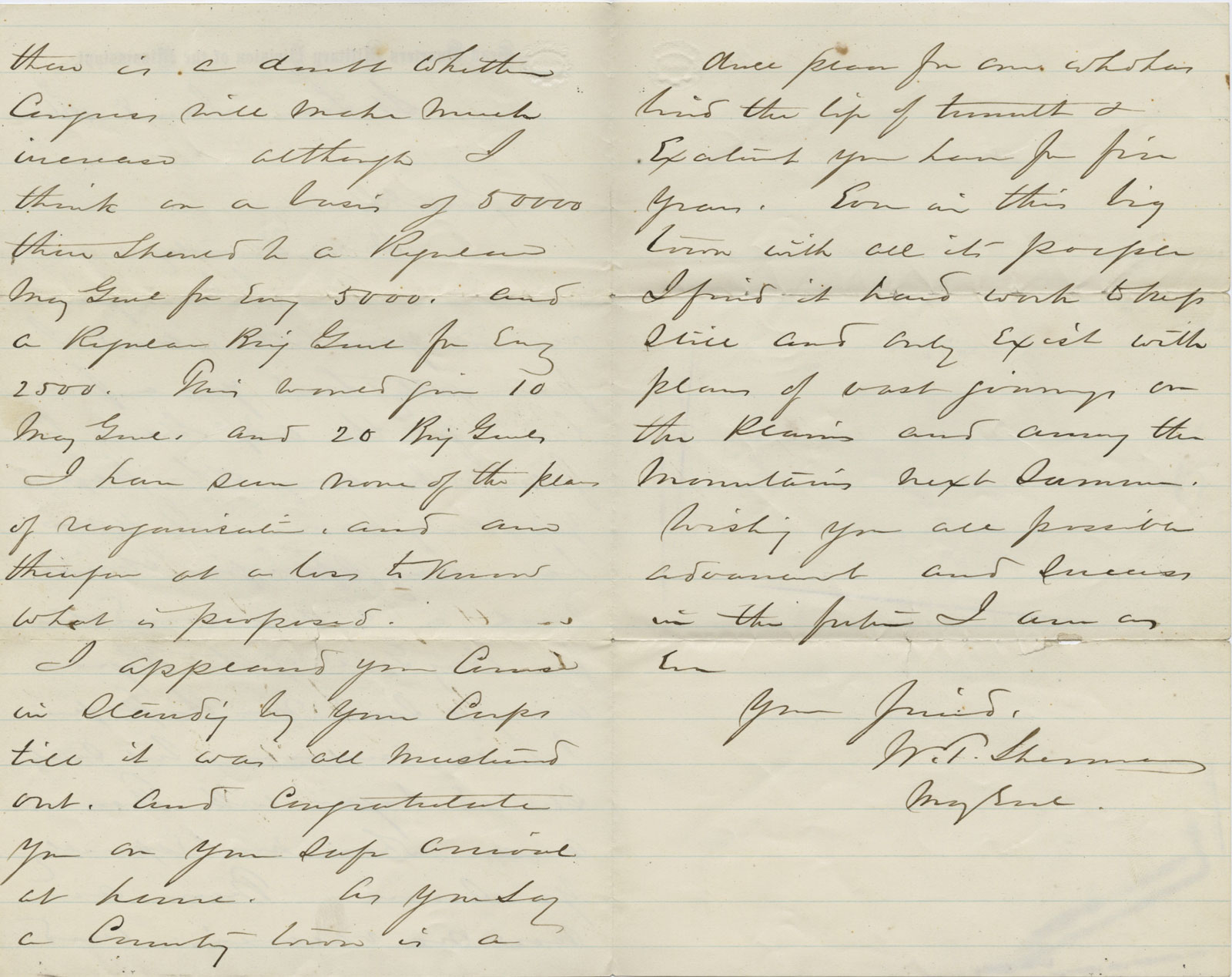

Autograph letter signed, on his Head Quarters Military Division of the Mississippi letterhead, St. Louis, January 8, 1866, to Stanley, saying he would support his application for a generalship, but didn’t know if he could secure one. He also expressed his own difficulty with adjusting to the post-war reality of his life. “I have just received your letter, and I promptly send you a few lines for the adjutant general to file with any other papers you may have. If you have any specific object, such as a recommendation for a Brig. General of the Regular Army and send me the papers, I will endorse, but such should begin with Thomas under whom especially you served. There are now no vacancies, and there is a doubt whether Congress will make much increase, although on a basis of 50,000 there should be a Regular Maj. General for every 5,000, and a Regular Brig. General for every 2,500. This would give 10 Maj. Generals and 20 Brig. Generals. I have seen none of the plans for reorganization, and am therefore at a loss to know what is proposed.

“I applaud your course in standing by your corps till it was all mustered out, and congratulate you on your safe arrival at home. As you say, a country town is a dull place for one who has lived the life of tumult & excitement you have for five years. Even in this big town with all its people, I find it hard work to keep still and only exist with plans of vast goings on the Plains, and among the mountains next summer. Wishing you all possible advancement and success in the future, I am as ever, W.T. Sherman, Maj. Genl.”

This unpublished letter gives us great insight into Sherman’s personal feelings about the stress, let-down and perhaps depression of returning home after active wartime service. We learn he was nervous, could barely keep still, saw towns and even cities as dull, and could “only exist” by imagining that there will be lots of military activity on the Plains against the Native Americans in the future. It is also the only letter we have seen in which Sherman expressed such feelings and difficulties, which he shared with Stanley and so many others.

As for Stanley, he was given a series of posts as a Colonel, ending in command of the Department of Texas. He did not, however, make general’s grade until 1884.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services