The Canal Era: Pennsylvania, Seeing the Tremendous Success of New York’s Erie Canal, Will Rise to the Occasion and Build Canals

The archive of Robert M. Patterson, first Canal Commissioner of the State

- Currency:

- USD

- GBP

- JPY

- EUR

- CNY

With manuscript and printed material documenting the work of the pro-canal Committee of 24 and the Pennsylvania Legislature to open westward communication

By the close of the year 1824 the State of New York’s chief internal improvement project, the Erie Canal, was nearing completion. It was already so successful that the state...

With manuscript and printed material documenting the work of the pro-canal Committee of 24 and the Pennsylvania Legislature to open westward communication

By the close of the year 1824 the State of New York’s chief internal improvement project, the Erie Canal, was nearing completion. It was already so successful that the state began to feel the positive economic effects – and also to promote them. It was rapidly tapping the commercial resources of the “new west”; trading was brisk; land values were increased; the influx of immigrants was adding to its population, giving rise to towns, and gaining for New York even greater potential economic strength. The rise of New York posed a challenge to the other states, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was the first to accept the challenge. Merchants, traders, bankers, and the foremost residents of Philadelphia were concerned with the jolt the Erie Canal gave to their economic bid for Eastern seaboard supremacy. During 1825 an extensive and unceasing campaign in favor of internal improvements took effect in the Commonwealth, and this was ably assisted by one small but influential group – “The Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Internal Improvements.” These men were determined to do something constructive to improve Philadelphia’s competitive position.

In the spring of 1824 Pennsylvania first took up the challenge. On March 26 the legislature passed a bill that authorized the governor to appoint a board of commissioners, comprising three men, for the purpose of collecting data and reporting on the feasibility of undertaking internal improvements – that meant, to all intents and purposes, a canal.

On Monday afternoon, January 24, 1825, a group met to consider the propriety of petitioning the legislature in respect to making arrangements for “opening a water communication between the Susquehanna and Allegheny rivers.” The idea met with the enthusiastic approval of many of the leading residents of Philadelphia who attended the meeting at the appointed time. This was the Committee of 24. Chief Justice William Tilghman presided; and Nicholas Biddle, president of the United States Bank, acted as the secretary. The meeting was opened by John Sergeant, president of the Pennsylvania Improvement Society, and Mathew Carey offered resolutions concerning the opening of a water communication between the Susquehanna and Allegheny rivers at state expense. Benjamin Chew, Jr., proposed an amendment to include a canal betwen Lake Erie and the Allegheny.

They reconvened on the 26th. At that meeting, Sergeant, on behalf of the original committee of seventeen, reported a preamble and resolutions, which were then debated and finally accepted by a large majority. These, in effect, advocated that at the earliest practicable moment there should be opened a system of water communication from the Susquehanna River to the Allegheny, and between the latter and Lake Erie, “at such points as the wisdom of a suitable board of skilful and experienced engineers may select.”

On February 18, Chairman Tilghman, as the subject was being openly debated in the Pennsylvania legislature, sent a committee to report the findings and lobby the legislature. This committee was composed of Robert M. Patterson, D.W. Coxe and Manuel Eyre. Patterson was selected because he was so well connected.

Robert M. Patterson was one of the nation’s foremost scientists of his generation. He studied medicine in Paris, then went to London where he heard the last course of lectures delivered by Sir Humphry Davy. In 1813 he was appointed professor of natural philosophy in the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania, and a year after (March 1814) was elected to the chair of mathematics, chemistry, and natural philosophy. He was also a noted astronomer. He was soon made the university’s vice-provost. Patterson was a friend and correspondent with Thomas Jefferson, and a member of the American Philosophical Society. In 1813 he was elected the Society’s secretary, and then vice-president in 1825. It was he who informed Jefferson of his re-election as President of the Society, a position he would later occupy. Patterson would go on to serve as Director of the U.S. Mint.

This committee reported back to the Committee of 24 and Tilghman, sending resolutions and the results of their work. They were successful and Pennsylvania passed an “Act to appoint a Board of Canal Commissioners,” authorizing the governor to appoint five men to the board. Patterson was one of those five who received an appointment.

This is Patterson’s archive, acquired from his direct descendants, and published in part and offered for sale here for the first time.

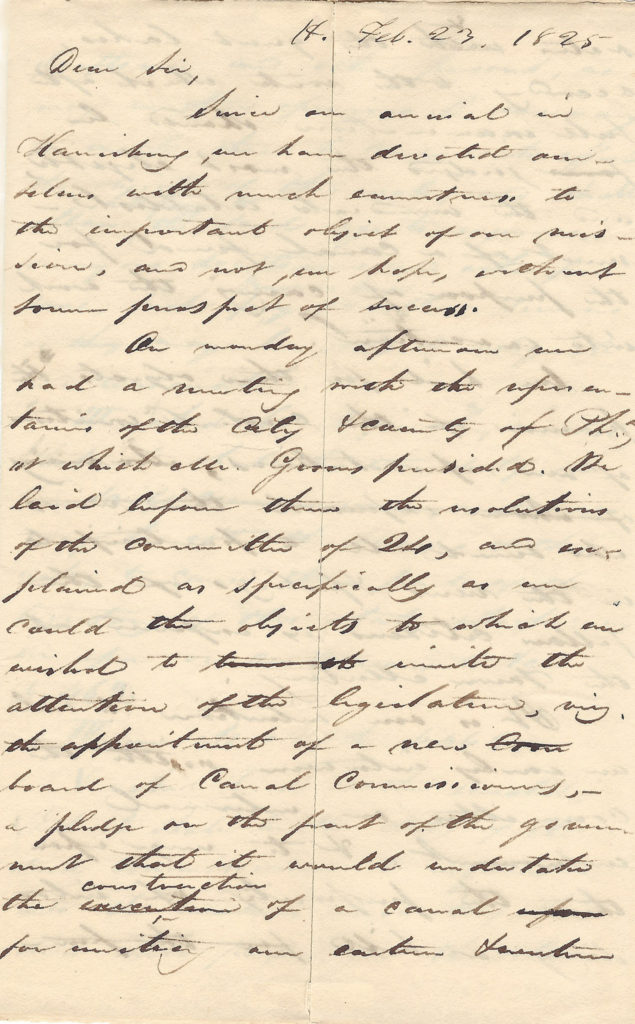

Autograph letter signed, by Nicholas Biddle as Secretary and William Tilghman as President, February 18, 1825, to Robert Patterson, Manuel Eyre, and D.W. Coxe, 2 full pages, informing them that they will present the report of the committee and giving them instructions. “…You visit Harrisburgh in order to represent to the government the earnest and anxious wish of the citizens of Philadelphia that the connection of the Eastern and Western waters and the lakes should be immediately undertaken…”

Document signed, Nicholas Biddle, Secretary, February 14, 1825, an original act of the committee. “Resolved, That in the opinion of the committee the great object which ought to be steadily and constantly kept in view is the opening a communication by water with the least possible delay and by the best practicable route, between the East and West… Resolved, that the committee now appointed to proceed to Harrisburg be instructed to use their best exertions in favor of such measures….”

Printed document, docketed by Patterson, the minutes of the meetings on January 24 and 26, 7 pages, announcing the creation of the committee; appointment of Tilghman and Biddle to lead the committee; the broad goals of the newly created committee; the composition of the committee; the letter to the Senate and House of Representatives stressing the importance of their task, dated January 31.

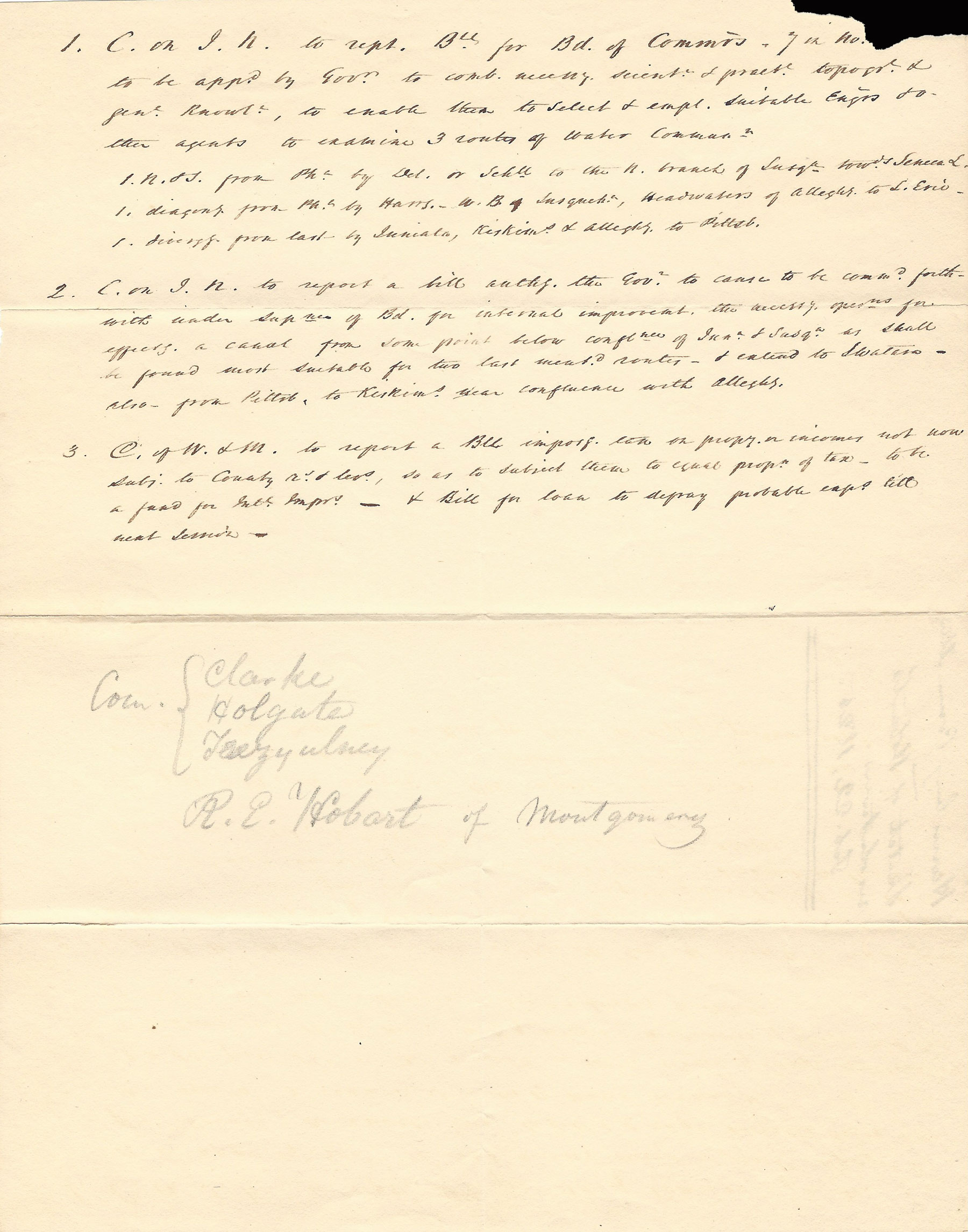

Manuscript, docketed by Patterson, February 22, 1825, a “sketch of Hobart’s resolutions,” authorizing the creation of the Board of Canal Commissioners, referencing the bill by R.E. Hobart.

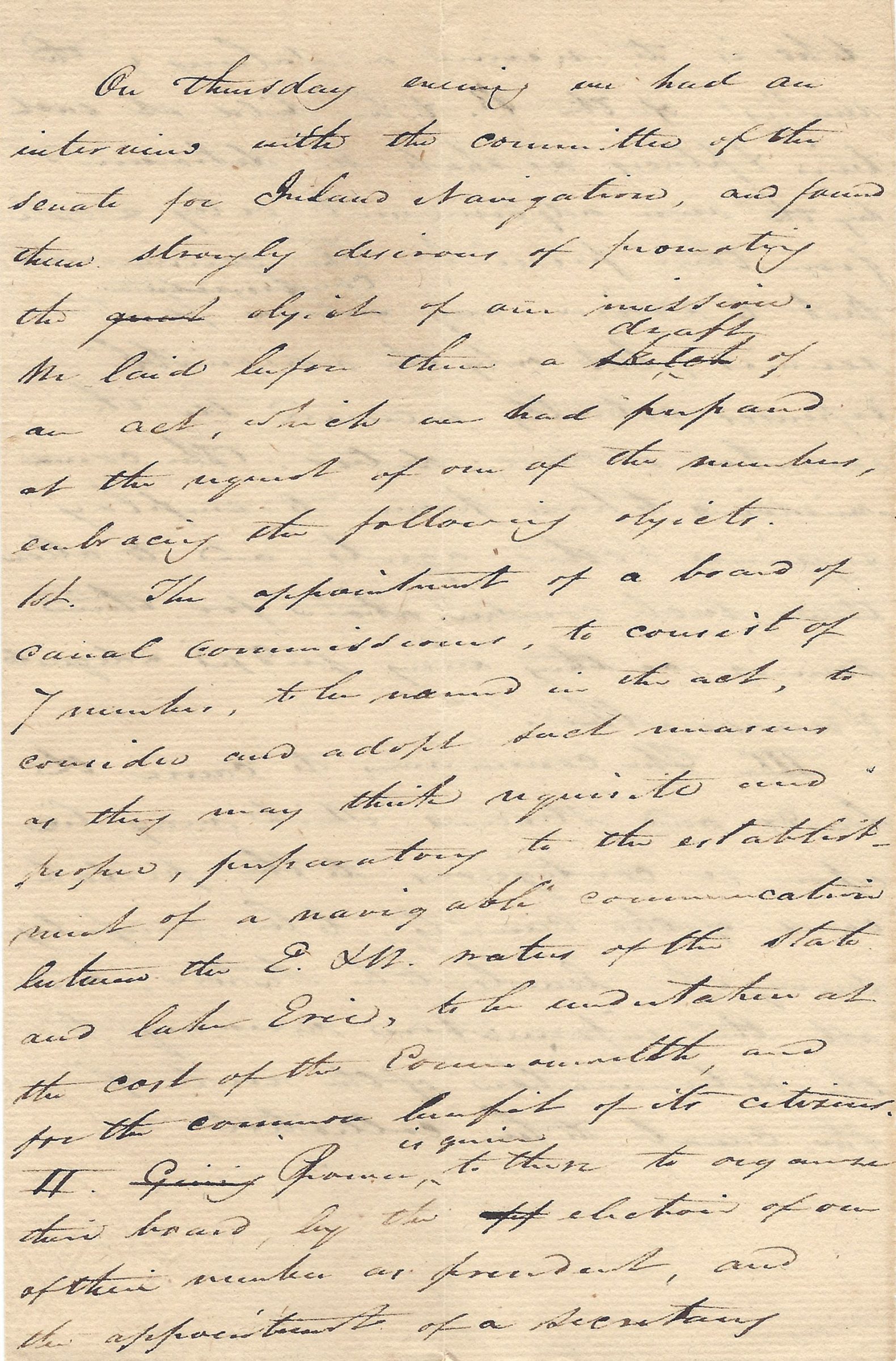

Draft Autograph Letter, February 23, 1825, 7 pages, by Robert M. Patterson, being a draft to Chief Justice Tilghman from the committee sent to Harrisburg, announcing that they had laid before the legislature the work of the committee of 24, that this proceeded well, and discussing the proposed Board of Canal Commissioners, listing the language and main points of the act, and inclosing copies of the acts.

Above included: Autograph drafts of various bills in front of the Pennsylvania legislature.

Draft Autograph letter, no date but late February 1825, announcing a meeting with the Committee of Inland Navigation.

On May 9, 1825, Patterson’s committee convened for the first time, giving their report to the Governor seven months later in December. The state legislature passed an Act in February 1826 officially sparking “the commencement of a canal to be constructed at the expense of the state and to be styled The Pennsylvania Canal.”

The Pennsylvania Canal was once one of the most impressive and intricate networks of its kind in the United States; in its heyday it was integral to both intrastate and interstate commerce. With crude nineteenth century pick axes and tools Pennsylvanians labored tirelessly to complete approximately 1,250 miles of canal waterways.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services