Chief Justice John Marshall Supports the Growing American Interest in Science and Medicine, Upon the Opening of What Is Now the George Washington University Medical School

He takes a position consistent with his opinion in the famous case of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, where he wrote that “…education is an object of national concern.”.

In 1799, George Washington expressed in his will his “ardent wish” for a university to be established in the District of Columbia. He dreamed of a place “to which the youth of fortune and talent from all parts [of the country] might be sent for the completion of their education in all...

In 1799, George Washington expressed in his will his “ardent wish” for a university to be established in the District of Columbia. He dreamed of a place “to which the youth of fortune and talent from all parts [of the country] might be sent for the completion of their education in all the branches of polite literature, in arts and sciences, in acquiring knowledge in the principles of politics and good government.” Washington believed the nation’s capital was the logical site for such an institution and left a bequest toward that objective. Washington died before his vision was carried out. However, Rev. Luther Rice and three other friends took up the effort; President James Monroe and 32 members of the U.S. Congress also became involved. On Feb. 9, 1821, Monroe signed the Act of Congress that created the Columbian College in the District of Columbia, a private, nonsectarian institution. In time, the name of the school would be changed to George Washington University, and so it remains known.

“It is truly gratifying to observe the progress made by our country in science generally, and especially in the very important department of medicine.”

The Columbian College opened its doors with three faculty members, one tutor and 30 students in a single building. Its curriculum included English, Latin and Greek, as well as mathematics, chemistry, astronomy, reading, writing, navigation and political law. The first graduates received degrees in December 1824. In 1825, Columbian College added a medical school (known initially as the National Medical College), becoming just the 20th medical school ever opened in the United States. Today it is the eleventh oldest surviving medical school.

Dr. Thomas Sewall graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1812 and practiced medicine in Massachusetts and then in Washington, DC. When the Columbian College was authorized in 1821, he took a post as professor of anatomy, and in 1825, with the institution of the medical school, became a founding faculty member there, again holding the post of professor of anatomy. He even gave a speech at the school’s opening.

In July 1825, Sewall sought to write a history of medicine in the United States, but found he had insufficient information on the state of Virginia. He wrote noted Virginians including Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall (who was also a biographer of George Washington), asking them if they had information on medical practice in their home state. They were unable to help. Some months later, he again wrote to provide them, and also to James Madison, with a circular about the newly-launched Columbian College medical school. His letter to Madison, which survives, surely serves as a template for what he wrote Marshall. Sewell stated that he believed “you still cherish an interest in [American] literary & scientific institutions,” adding for that reason, “I take the liberty to forward to you the circular of the Medical School recently instituted together with a copy of an introductory lecture delivered at its opening…”

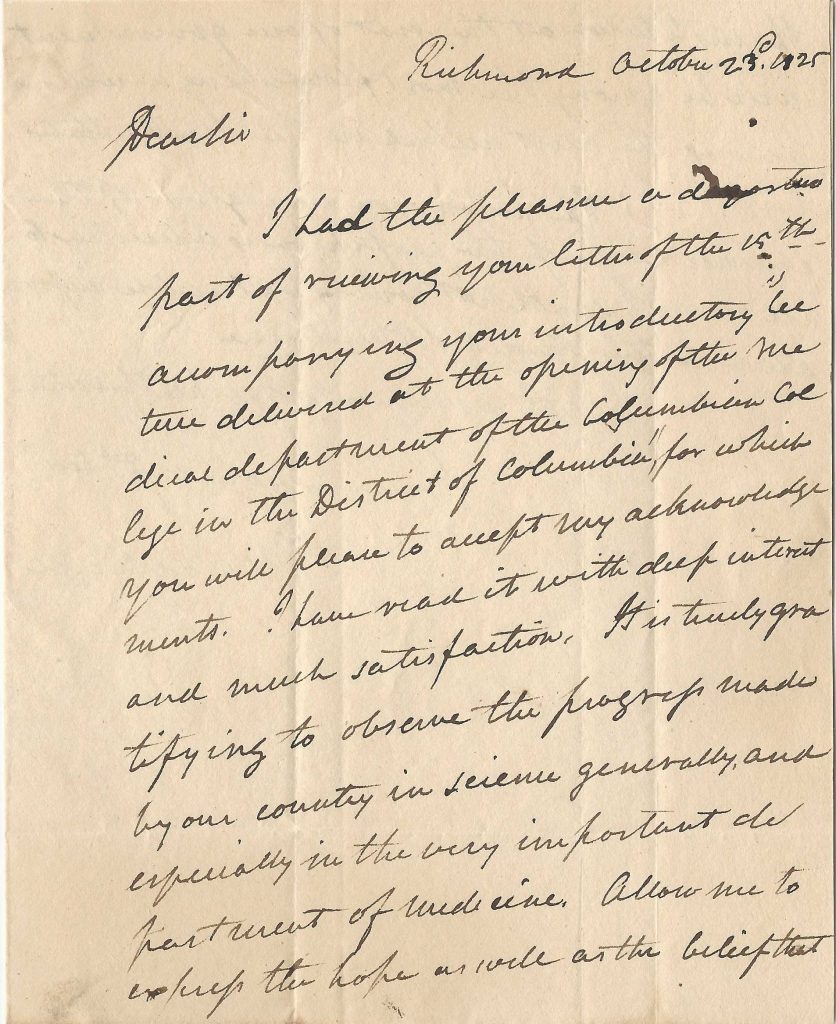

Autograph letter signed, two pages, Richmond, October 23, 1825, to Sewall, praising the advances the fledgling United States was making in science. “I had the pleasure a day or two past of viewing your letter of the 15th accompanying your introductory lecture delivered at the opening of the medical department of the Columbian college in the District of Columbia, for which you will please to accept my acknowledgments. I have read it with deep interest and much satisfaction. It is truly gratifying to observe the progress made by our country in science generally, and especially in the very important department of medicine. Allow me to express the hope as well as the belief that the institution at the seat of our government will be among the most flourishing as well as among the most useful in the United States. The history of the eminent men of the profession is interesting to all, & will I doubt not convey valuable information to the students of medicine.” It is signed “J. Marshall”. The integral address in Marshall’s hand, docketed by Sewall, is still present, bearing the postmark of October 24.

Marshall was a great supporter of education, as can be seen in his landmark opinion in the famous case of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, in which he wrote, “That education is an object of national concern, and a proper subject for legislation, all admit.” Nonetheless, it is unusual to find letters of Marshall on the growth of knowledge in American arts and sciences. In fact, a search of public sale records going back 40 years fails to turn up even one letter of his (other than to Sewall) on education, science or medicine.

Letters of Marshall as Chief Justice are increasingly uncommon.

Frame, Display, Preserve

Each frame is custom constructed, using only proper museum archival materials. This includes:The finest frames, tailored to match the document you have chosen. These can period style, antiqued, gilded, wood, etc. Fabric mats, including silk and satin, as well as museum mat board with hand painted bevels. Attachment of the document to the matting to ensure its protection. This "hinging" is done according to archival standards. Protective "glass," or Tru Vue Optium Acrylic glazing, which is shatter resistant, 99% UV protective, and anti-reflective. You benefit from our decades of experience in designing and creating beautiful, compelling, and protective framed historical documents.

Learn more about our Framing Services