Eleanor Roosevelt to Franklin’s mother: “The other room on 3rd floor should have 2 kids also. Two gentlemen in waiting go in Elliott’s room, 3 maids in nursery, 2 valets in other 3rd floor room, 2 Scotland Yard men in Mr. Qualters room. The colored butlers can go in servant’s rooms in house and over stable…On the 10th of June we will arrive in the morning. The British party will not arrive until about 6:30 or 7:00 p.m. I will bring up on the train any things which seem essential for the rooms…” The King and Queen to Mrs. Sara Roosevelt: “We so much enjoyed our visit and will always cherish the happiest memories of your charming and united family.” Mrs. Sara Roosevelt to the King and Queen: “Your visit meant much to us and we shall always treasure the thought of it.” This archive appears to be unpublished

Thoughout the summer of 1938 the eyes of the world were focused on the threatening demands being made by Adolf Hitler on lands that were part of Czechoslovakia. Europe teetered on the brink of war, as Britain and France nominally supported Czechoslovakia, but in reality were not willing to go to war to save her. On September 13 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain asked Hitler for a personal meeting to find a peaceful solution. Chamberlain arrived by plane in Germany on September 15 and met with the Fuhrer; the result was a solution that would dismember Czechoslovakia. After the meeting, on September 16, French Prime Minister Edouard Daladier flew to London to meet British officials to discuss a course of action. They determined to pressure Czechoslovakia to make concessions, to essentially abandon Czechoslovakia in the hopes of avoiding another world war. The next day Hitler established a paramilitary organization of ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia. At the end of the month, Hitler, Mussolini, Chamberlain and Daladier met at Munich to sign the infamous Munich Agreement, appeasing Hitler and convincing him that Britain and France were weak and would never stand up to him. On October 5, Winston Churchill would warn the British people that “they should know that we have sustained a defeat without a war, the consequences of which will travel far with us along our road. He also stated, “At Munich the Government had to choose between war and shame. They chose shame. I tell you, they shall get war, too.”

At that time, September 1938, U.S. foreign policy was isolationist. Relations with Britain were cold and distant at best, with much anti-British sentiment and anger about having been dragged into World War I. As war loomed in Europe, a September 23, 1938, Gallup poll showed that Americans wanted no part of European squabbles, and 73% were in favor of maintaining a mandatory arms embargo on all sides. Franklin Roosevelt was an exception to these sentiments, as he was already convinced that the Nazis would bring war soon enough, and that the United States would not be able to avoid choosing sides. He wanted the U.S. to provide assistance to Britain, but first had to persuade the public that it was both a good idea and that the British were worthy of the risk the U.S. would be taking by getting involved. There was an ongoing and intense debate within the U.S. over potential intervention, and it was a very critical time in relations between Britain and the U.S.

As the events of September 1938 were taking place, Roosevelt learned that British King George VI and his wife Queen Elizabeth (known as the Queen Mother when her daughter Elizabeth ascended the throne) were planning to visit Canada to try to rebuild royal esteem in the wake of the abdication of George’s brother King Edward VIII less than two years earlier. FDR wrote to the King almost immediately. His letter, dated September 17, 1938 and delivered by Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, stated: “I think it would be an excellent thing for Anglo-American relations if you could visit the United States… It occurs to me… that you both might like three or four days of very simple country life at Hyde Park — with no formal entertainments and an opportunity to get a bit of rest and relaxation.” In the King’s reply, written on Balmoral Castle stationery and dated October 8, 1938, he accepted the invitation, adding: “I can assure you that the pleasure, which it would in any case give to us personally, would be greatly enhanced by the thought that it was contributing in any way to the cordiality of the relations between our two countries.” Diplomacy is written between the lines. And FDR, a master of the art, planned not only to meet with the King and Queen but to present them as “regular people” to the American public. What better way than with an informal – yet highly publicized – picnic at Hyde Park, full of good feelings and good fellowship. That the King and Queen had a similar purpose is clear from his letter.

The State Department, however, quashed that idea, and FDR had to acquiesce to a more formal visit befitting a head of state. However, he did win the most important battle: the King and Queen would indeed visit Hyde Park, though for a short stay; and that would allow Roosevelt to turn his plan into a reality. But there was another key person whose cooperation FDR needed to enlist to arrange for the Hyde Park visit, someone distinctly outside government channels: his mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt. She was not only the occupant of the estate on the Hudson River, but the owner; she was pleased about the idea, however, so the stage was set.

The King and Queen’s visit was planned for June 1939. When the spring of 1939 arrived, and with it the visit, Europe was simply awaiting the outbreak of war, and Roosevelt realized the immediate necessity of fostering closer ties between the two democracies. He determined to pursue a change in U.S. foreign policy as soon as feasible, even at the risk of losing domestic support from the very strong and vocal isolationist and anti-British segments of the electorate. So FDR and his wife First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt planned every minute detail of the visit to ensure the success of the King and Queen in winning over the sympathy and support of the American people. The event must go forward without a flaw, and by mid-May 1939, with the visit less than a month away, the time had arrived to work out the logistics at Hyde Park. FDR assigned this task to Eleanor, who knew the details of the royal couple’s entourage, knew the Roosevelt home, and could be relied on to make sure everything went off swimmingly. Eleanor had to coordinate the arrangements with Franklin’s mother, who had responsibilities and would need to handle aspects of the event on site. Considering the strained relations between the two Mrs. Roosevelts, the prospect could not have been welcoming.

This is Sara Roosevelt’s personal file relating to the royal visit to her home.

It includes three letters from Eleanor to Sara, the first two detailing what was expected of Sara, and the latter walking her through the schedule. There is also a telegram of gratitude from the King and Queen to Sara, her manuscript telegram to them in response saying she would cherish the memory of their visit, a very rare original program for the event sent right from the White House, and other artifacts. The letters show the First Lady’s great attention to detail, and dedication to making the Royal Family and their entourage comfortable and happy.

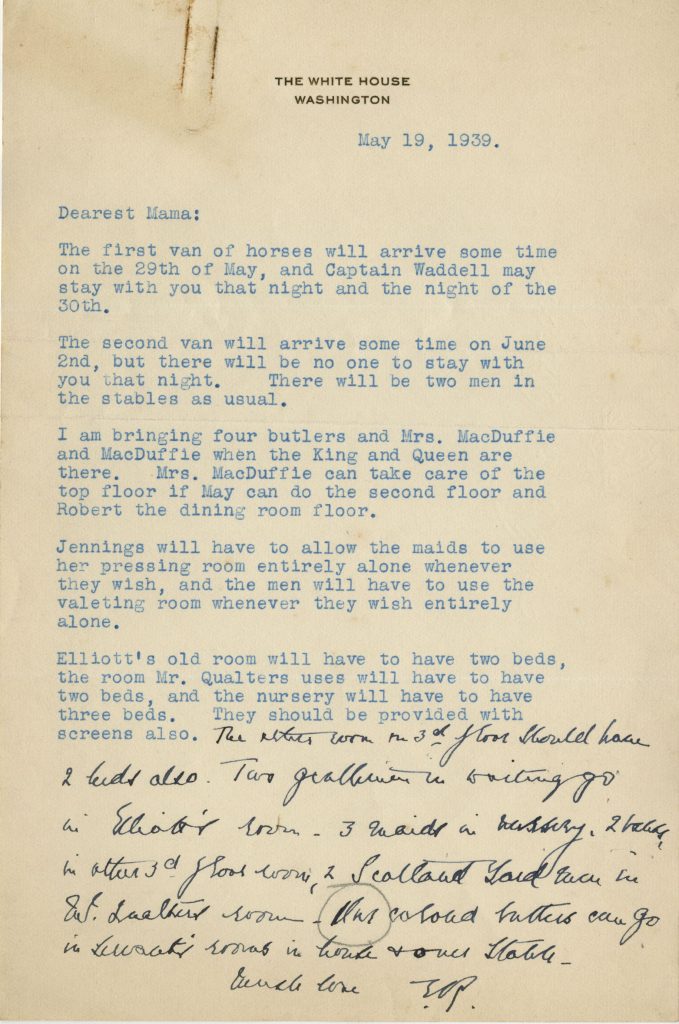

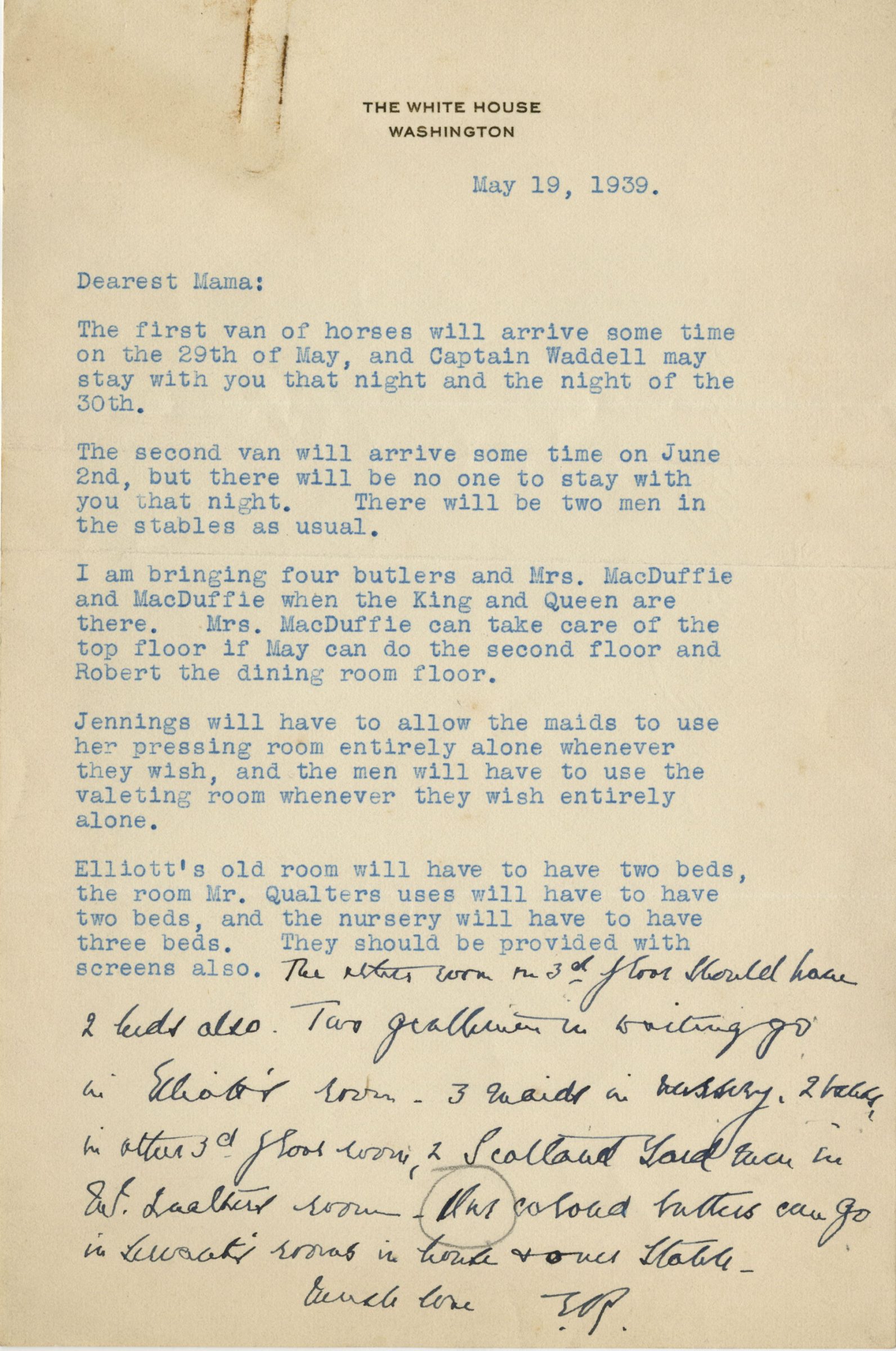

The earliest communication is a typed letter signed from Eleanor, on White House letterhead, Washington, May 19, 1939, addressed “Dearest Mama”, giving the personal and household logistics. “The first van of horses will arrive some time on the 29th of May, and Captain Waddell [Eleanor’s groom] may stay with you that night and on the night of the 30th. The second van will arrive some time on June 2nd, but there will be no one to stay with you that night. There will be two men in the stables as usual. I am bringing four butlers and Mrs. McDuffie and MacDuffie [Lizzie McDuffie was the White House maid and Irvin McDuffie was FDR’s valet] when the King and Queen are there. Mrs. McDuffie can take care of the top floor if May can do the second floor and Robert the dining room floor. Jennings will have to allow the maids to use her pressing room entirely alone whenever they wish, and the men will have to use the valeting room whenever they wish entirely alone.” May, Robert and Jennings were clearly on the Hyde Park service staff.

Eleanor continued, “Elliott’s old room will have to have two beds, the room Mr. Qualters [Thomas Quarters was responsible for FDR’s security and physical assistance] uses will have to have two beds, and the nursery will have to have three beds. They should be provided with screens also.” She has added in holograph, “The other room on 3rd floor should have 2 kids also. Two gentlemen in waiting go in Elliott’s room, 3 maids in nursery, 2 valets in other 3rd floor room, 2 Scotland Yard men in Mr. Qualters room. The colored butlers can go in servant’s rooms in house and over stable. Much love, E.R.”

Later that day, Eleanor sent a follow up letter, also addressed “Dearest Mama.” “Will you have your cook make green salad enough for the picnic? There will be about 100 people. And will you see that there is enough milk, cream and butter on hand? I will provide the rest of the food.” She has added in holograph, “You are in for a great many memos from now on! Much love, Eleanor.” It seems, however, that after her lengthy letter the following day, there was no further need for memos.

The next day the schedule was laid out. Typed letter signed, on White House letterhead, Washington, May 20, 1939, addressed “Dearest Mama”, and walking her through the chronology of events. “In writing you yesterday I forgot to tell you that Frankin will get in on Saturday morning, the 27th, and stay with you until Tuesday. Missy [LeHand, FDR’s private secretary] will be the only one with him, and he will bring just McDuffie and Mr. Qualters. On the 10th of June we will arrive in the morning. The British party will not arrive until about 6:30 or 7:00 p.m. I will bring up on the train any things which seem essential for the rooms or bathrooms, etc. On Sunday, June 11, everyone will go to church and will have a card of admittance. Mr. Wilson [Alexander Wilson, rector of St James Church, which the Roosevelts attended] knows all about it and will give all the cards to his parishioners. Bishop [George] and Mrs. Tucker will stay with the Lydig Hoyts, who have asked them, and Bishop Tucker will preach the sermon.

“After church we will all return to the Big House to change, and then Franklin wants you to drive down to the woods with him and the King and Queen before before going up to his cottage for the picnic. I will send you the lists for both of the dinners and the picnic in the course of the next few days, and I will send you those who have accepted and refused. After the picnic Franklin has not decided whether he wants to take them for a drive and then go back to the pool for a swim or whether he will let them take a walk and then go for a swim.” He chose the drive, and FDR himself was at the wheel; in later years the Queen recalled that ride as “exciting”.

“There will be dinner that night, and the King and Queen will leave at 11:00 p.m. The next morning Franklin leaves at 10:00 for West Point for commencement exercises. I do not know whether you are planning to go with him? He has inited, at my request, three people from Spokane who want to see him and that seems to be the only way to do it. I am going down to the commencement with him and return to the cottage after that. We may go west on the 15th of June, but Franklin will not be able to decide until early in June. It will be a short visit to the Fair [the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco] and if he does not take it in June he will go later. Is there any chance that you would like to go on this trip to the Fair? Much love, Eleanor.” It is fascinating and indicative to see that even at this time, Eleanor was arranging for advocates of causes she believed in to see her husband, something he was not fond of but did to keep her happy. Most likely the Spokane group was asking for a bridge over the Spokane River, as one was commissioned soon after.

The King and Queen came into the U.S. on June 7, becoming the first reigning British monarch to set foot in its former colony. When they arrived in Washington on June 8, 1939, Americans heartily welcomed them with thunderous applause and adulation. Crowds lined the streets for a chance to catch a glimpse of them as they traveled throughout the city. In Washington, the couple was treated to all the formalities one would expect from a state visit. There was an afternoon reception at the British Embassy, followed by a formal evening of dining and musical entertainment at the White House. On their second day, the King and Queen took in the sights of DC as they boarded the presidential yacht and sailed down the Potomac River to George Washington's Mount Vernon, stopped by a Civilian Conservation Corps camp (a work-relief camp for victims of the Depression), and then motored to Arlington Cemetery to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Then the tone of the visit changed from formal to informal, as the royal couple toured the World’s Fair in New York City, and there was much publicity giving a glimpse of their enjoying it.

On June 10 the King and Queen accompanied the Roosevelts to their home in Hyde Park, their stay there illustrating to the American people that although they were royalty, they also enjoyed the simpler things in life. In contrast to the formal State Dinner at the White House, dinner at the Roosevelt's home was described to the press as a casual dinner between the two families; their evening entertainment was simple conversation, unfettered by formalities. Just as informal was the following day's event – a picnic. FDR brought the couple to his new hilltop retreat, Top Cottage, on the eastern portion of his estate for an old-fashioned, American-style picnic. The King and Queen were served hot dogs on the front porch of the cottage. Although the press made a great deal about the hot dogs (the picnic made the front page of the New York Times), the menu also included more delicate fare fit for a King and Queen.

Although the visit appeared to be purely a social affair, interspersed with the pomp and circumstance were serious discussions between the President and the King about the political and military situation in Europe. During this short visit their discussions gave way to policies such as the "destroyers for bases" deal and the decision to provide long-range U.S. Navy patrols in support of the Royal Navy's convoy escort groups during the Battle of the Atlantic. More importantly to Franklin Roosevelt, however, was that this visit changed the perceptions of the American people, which in turn allowed him to do more for Britain. When Britain declared war on Germany three months later, Americans, due in no small part to the King and Queen's visit, sympathized with the United Kingdom's plight; Britons were no longer strangers or the evil colonial rulers from the past but familiar friends and relatives with whom Americans could identify. This took tangible form when on September 21, 1939, FDR appeared before Congress and asked that the Neutrality Acts, a series of laws passed earlier in the decade that precluded assistance to Britain, be amended. Roosevelt hoped to lift the embargo against sending military aid to countries in Europe facing the onslaught of Nazi aggression during World War II. Congress agreed in November; the same result would have been unthinkable just six months earlier.

The archive contains three autograph letters signed from Sara to a friend, directly revealing her own personal impressions of the visit. The first is dated from Hyde Park, June 7, 1939, and mentions her feelings about the visit. “We are getting in order & four flags have come & are being placed on our Georgian porch. & I am going to have a crimson carpet on the front terrace….Will be joy seeing the K. & Q. My sister got off & I left her flowers for you! What perfect weather just now! The clergy, two couples, will stop in my house tonight & Anna [likely her granddaughter] will give them breakfast tomorrow morning!” The second letter is from June 9, after she had met the royal entourage in Washington and the day before the Hyde Park visit would begin. “The flags four in number are arranged & the lovely new red carpet fitted & the house is really ’spick & span’…”

The third letter is written June 12, in the immediate wake of the visit. “…The Royal party was charming, & they were here for two dinners, & the picnic all went perfectly, & we were 30 one day and 34 the next at dinner. Genuinely sorry to [see them] leave last evening at 10:30. We all saw them off from the station at 11 p.m. I am now alone & the family went to West Point & will be thence to Washington, etc.”

After arriving in Canada, the King sent Sara Roosevelt a warm telegram of gratitude, the original of which is included, and states: “The Queen and I thank you from our hearts for your kind hospitality. We so much enjoyed our visit and will always cherish the happiest memories of your charming and united family.” Mentioning the happy unity of the Roosevelt family seems a poignant allusion to the split in the royal family caused when King Edward VIII abdicated and left the arduous and unwelcome job of kingship to his younger brother George. Sara sent them a telegram in reply, the original autograph manuscript of which is in this archive. “Their Majesties King George Sixth & Queen Elizabeth. Thank you for your very kind telegram. Your visit meant much to us and we shall always treasure the thought of it. May you have a comfortable voyage & a happy return home. Sara D. Roosevelt.” She wrote this on the verso of a note from Eleanor’s secretary in the White House, sending Sara “this souvenir of the King and Queen’s visit…which was printed in the United States Government Printing Office.”

The 16-page souvenir is a program, and is entitled “Program State Visit of Their Britannic Majesties, June 1939.” It lists all the members of the royal party, and contains a detailed description of what would happen and when, from the time the advance party gathered on June 6, through the arrival of the royal party on the 7th, to the full schedule for the two days of formal receptions in and around Washington, then on to New York and Hyde Park, and right through their departure. This is a very rare imprint, and provides important information on such seldom-recalled aspects of the visit, as the welcoming committee and a list of those who were presented to the King and Queen. Also included is the 21-page program for events at the White House on June 8 and 9, listing the extraordinary variety of people presented to the royal couple, from cabinet members to diplomatic personnel, to relatives like FDR’s uncle and Eleanor’s brother. The music they heard at the dinner was designed to be distinctly American, and included music acknowledging the contribution made by “Negro” music. The other imprint is Sara’s copy of the card handed out to attendees at the Hyde Park arrival, reading: “Guests will be presented to the President and Mrs. Roosevelt and the King and Queen immediately upon arrival at the President’s cottage. Guests are requested to take seats under the trees where luncheon will be served to them.” Lastly in the archive are 12 wire service photos of events during the King and Queen’s visit to the U.S. and Canada.